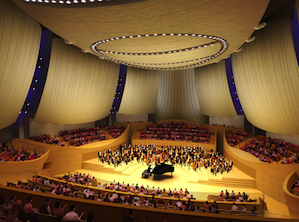

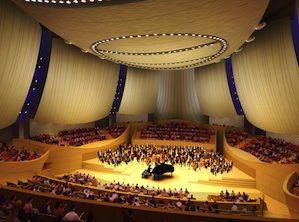

I can’t wait to hear La Mer in Stanford University’s bold new Bing Concert Hall — a sweeping, circular space with giant convex “sails” and wavy, linear forms that were acoustically designed to scatter the sound waves rolling around this dynamic yet intimate 850-seat room.

Even the backs of the beech-wood seats — clustered in curved terraces ringing the pale-yellow cedar stage where everyone from Yo-Yo Ma to Los Lobos will perform during the inaugural season starting Jan. 11 — form an undulating line.

“We just didn’t know when to quit,” said architect Richard Olcott, a tall, cool, and witty customer. “There are no straight lines in here.”

Olcott, the designing partner at Ennead Architects in New York, whose other music projects include the 750-seat Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall, designed the Bing with acoustician Yashuisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics, best known for his contribution to Frank Gehry’s dazzling Disney Hall in Los Angeles.

That much larger “vineyard”-style oval hall, famous for its swooping rhythms and titanium-clad forms, informed the thinking about the Bing. So did the landmark 1963 Berlin Philharmonic Hall — a vineyard design with all straight lines — and Vienna’s beloved, 19th-century Musikverein, a 1,700-seat hall designed in the other favored form: the classic, high-ceilinged shoebox.

“We just didn’t know when to quit. There are no straight lines in here.” –Richard Olcott, lead architect

That’s the shape of halls like the Boston Symphony’s, the smaller Ozawa Hall at the symphony’s summer home at Tanglewood, and the new Weill Hall at Sonoma State, designed by the same architect, William Rawn. (A vineyard might have seemed the logical choice for wine-soaked Sonoma, but never mind.)

Planning a Vineyard Hall for the “Farm”

Olcott, a Cornell man who has designed three other buildings on the bucolic campus called “the Farm” over the last 15 years — the Stanford law school, the Cantor Arts Center, and the soon-to-be-built gallery for the Anderson collection of 20th-century American art — presented both shoebox and vineyard schemes to the high-powered Stanford planning team that had already done its homework and had a pretty good idea what it wanted.

“The one everyone latched onto was the one we described as ‘a clearing in the woods,’ which was an oval building. That’s how we got this job,” Olcott said. He had the freedom to make a contemporary building on the wooded site where the ruins of the university’s original gymnasium, destroyed by the 1906 earthquake, made way for a structure that didn’t have to speak directly to the Romanesque stone arches and Mission Revival red-tile roofs of the 19th-century buildings on Stanford’s beautiful main quad.

“There’s a lot of historical precedence over there. It’s like going to a dinner party where every one is very well-dressed,” the architect said. He was standing in the gracefully curving, glassed-in lobby, which looks out to an autumnal, Northern California landscape of oaks, Monterey pines, and sycamore trees, which were shedding leaves that might be described as Stanford red. Looking into the hall from outside, you see a similar orange-red tone on one of the exposed walls of the oval “drum,” as Olcott calls the sand-colored concert-hall shell, which shoots up through the lobby to the sky.

The in-the-round vineyard scheme — so named because the gently sloping terraces suggested a vineyard to Hans Scharoun, the architect who designed the Berlin hall — “gets everyone as close to the stage as possible,” said Olcott, whose musical tastes run from opera to rock ’n’ roll. (He lit up, recalling a transcendent night listening to Simon Rattle and the Vienna Philharmonic play Beethoven’s Fifth at the Musikverein.)

The grouping of seats at the Bing in self-contained terraces “creates a sense of intimacy; you’re not sitting in a sea of seats.” And having the front row on the same level as the stage, Olcott added, enhances the sense of immediacy and community.

The Stanford community celebrates the opening of the $112 million hall, named for the philanthropic 1955 Stanford grads Helen and Peter Bing, with a weekend of performances, Jan. 11–13, that stretch from classical, jazz, and Latin music to electronic compositions and even Japanese taiko drumming.

First Shows Throw Everything at Bing, Sonically

The sold-out opening night bash, hosted by actress and former Stanford faculty member Anna Deveare Smith, features Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony with Frederica von Stade, playing — yes! — Debussy’s La Mer and John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine; Stanford’s in-residence St. Lawrence String Quartet; a new electronic work by faculty composers Chris Chafe and Fernando Lopez called Fanfares, which will show off the hall’s top-drawer audio systems; and various student ensembles.

The following night, Jan. 12, the great Mexican-American rock band Los Lobos plays its Latin numbers on acoustic instruments. The St. Lawrence Quartet returns the next afternoon, followed that evening by a host of Stanford choral, jazz, symphonic, and wind ensembles.

St. Lawrence violinist Geoff Nuttall, whose ensemble has played in the hall for select audiences, raves about the Bing’s acoustical clarity and richness.

“It’s devastatingly good. You can really hear yourself,” Nuttall told the press one recent morning.

Others onstage included fellow fiddler David Harrington of the Kronos Quartet, which premieres a new multimedia work with performance artist Laurie Anderson at the Bing next April. He’s hot to play there.

“To walk in here and see music valued this way is very beautiful,” said Harrington, laid-back in jeans, boots, and lumberjack shirt. He spoke about Kronos’ use of speakers and microphones, which he considers instruments. “A great hall only makes those kind of instruments better, too. I can’t wait to bring all our stuff in here and figure it out.”

Stanford Composer Writes Operas for Bing Hall

One of the people who heard the St. Lawrence play Schubert in the hall was composer Jonathan Berger, a Stanford professor who runs the school’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, CCRMA (pronounced “karma”), which puts on the annual Music and the Brain symposium. Berger has written two short, linked chamber operas specifically for the Bing, titled Heotokia and The War Reporter, which premiere in April. They both deal with hallucinations — the first of the schizophrenic variety, the second the post-traumatic stress type. Naturally, acoustical and musical hallucinations will be the subject of the Music and the Brain confab in March.

“To walk in here and see music valued this way is very beautiful.” – David Harrington, Kronos Quartet

“With both operas, the audience is essentially inside the brains of these delusional characters,” said Berger, whose scores mix live music with electronic sounds, surrounding the audience in the big sealed oval.

After hearing and performing music in Stanford’s acoustically wanting Dinkelspiel Auditorium and Campbell Recital Hall, the Bing is a dream.

“It sounds spectacular,” Berger said. “I heard the Schubert from four different places, and it sounded equally good all around.”

Getting the Acoustics Right

That’s what Toyota was after, of course.

“We wanted clarity, and also a rich sound, so we can hear everything from the stage everywhere in the hall,” the acoustician said.

“We wanted clarity, and also a rich sound, so we can hear everything from the stage everywhere in the hall.” – Yasuhisa Toyota, Nagata Acoustics

To achieve those qualities, Toyota and Olcott designed the convex, textured forms that also give the hall its visual punch and flow.

“The convex surfaces diffuse the sound rather than just reflect it back. That’s important. They’re scattering the sound.”

The sculptural white sails that envelop the hall are huge — 30-foot tall slabs of Fiberglas-reinforced plaster, sprayed with an acoustical finish called Baswaphon. Video can be projected on them. The rest of the design flowed from those curves. Floating 48 feet above the stage is an enormous, rubber-raft-shaped white “cloud” that reflects the sound downward and houses the lighting and sound systems.

Then there are the wavy-form, pearly gray acoustical panels made with Fiberglas-reinforced polymer and Portland cement. Their varying patterns were inspired by the reverse curves that appear in overlapping patterns in American minimalist Robert Mangold’s famous column paintings.

“The one thing you don’t want is a regular pattern, because that sets up regular sounds waves,” said Olcott, whose team has translated Mangold into 3-D. “We created panels that are sufficiently nonrepetitive to appear random.”

It all seems to have paid off. Olcott heard the St. Lawrence Quartet in the hall and was pleased, and also heard a student a cappella group, which floored him. He also listened to the Stanford mariachi band.

“That was different. I don’t think any of us were expecting that,” he said with a laugh. “I still haven’t heard the room full of people, or heard an orchestra. But yeah, it sounds great.”