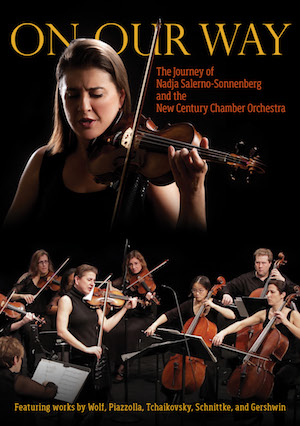

World-renowned violinist and New Century Chamber Orchestra Music Director and Concertmaster Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg packs heat.

The firepower is evident everywhere: striding onto stages nationwide ahead of the 19-string conductor-less ensemble; pushing to within inches as she instructs students in private lessons or master classes; performing and recording with brilliance and bravado NCCO’s classical and commissioned contemporary repertoire; or rocking out on the Jumbotron in front of 37,000 Giants fans at AT&T Park on a blustery day that — had music stands not been forgotten — would have spread sheet music across the San Francisco Bay Area.

“The publicist, Karen Ames, just held the music up for us, and we played our hearts out,” recalls associate concertmaster Dawn Harms. “It was an absolute blast, and something I'll never forget.” During a phone interview with Salerno-Sonnenberg while she is on the East Coast, the distance to San Francisco and a sound-smoothing Bluetooth does nothing to lessen the impression of radiant, blistering heat. Although “Flash” has been her mode and her nickname since she was 14 years old, “Inextinguishable Flame” might better suit the energy she projects.

Which is why Salerno-Sonnenberg’s departure at the end of the 2016–2017 season begs questions: Why leave? Where is she headed? What has been her impact on NCCO? What will become of the orchestra she has led — and in ways subtle and profound, been led by the astute, estimable ensemble — since coming onboard in 2008?

Answers to the first two questions are simplest. Salerno-Sonnenberg is leaving because she has accomplished her primary goals in coming to NCCO: to increase the orchestra’s visibility and to test and expand her skill set as an artist and leader of an ensemble. Mostly, she is leaving because having taught on the periphery of a busy, 30-year performing career, she feels an urgent desire to teach full-time. She has accepted a position to lead the newly formed Resident Artist Program at Loyola University’s School of Music in New Orleans. “I have so much information and knowledge in my body,” she says. “It’s like a virus; I have to get it out of me.”

Aware that she has primarily made her mark and inspired professional musicians while performing, Salerno-Sonnenberg says dedicating her energy to changing a student’s life now offers the greatest satisfaction. In other words, she’s become hooked on the joy that sweeps across a student’s face when coaching results in a difficult passage becoming playable or when a student realizes the secret to increased endurance is to relax a wrist, practice with greater intensity, maybe meditate, or do core-strength training. “The value in teaching is that I feel I’m doing something worthwhile,” she says. “Being with students on an ongoing basis, when you have more impact on their growth, it’s such a responsibility.”

But simple reasons for her next steps do not mean the decision was easy or quick. “It sat with me for many years,” she says. “I’m very fast once I’ve decided, which is how I’ve accomplished so much in my career. But life decisions, I have to ingest and digest.”

Hardest is leaving behind the people who have become like family. She says the one piece of advice given to her by every music director and conductor she consulted when deciding whether or not to join NCCO — advice she ignored — was to not get personally involved with the musicians. Instead, she learned about their lives, using the information to determine when to be a diplomat or play the “bad cop,” relying on closeness and familiarity to build trust. In performance, that trust was strapped on like a seatbelt, allowing the orchestra to follow Salerno-Sonnenberg if she took a musical phrase on a wild ride they’d not rehearsed. “My instincts come shining through in performance,” she says, “so it was fabulous, almost inexplicable, powerful, to have their trust.”

Nor does her gratitude and respect for the ensemble cause doubt. Surprisingly, it fosters appreciation for aging. “It’s hard on my heart, but it’s the right thing to do. It’s my absolute passion to live and do things a certain way. You get older and have no patience for wasting time. Achievement or not disappointing someone is for when you are younger. Doing for others is terrific, wonderful, but doing for self becomes important. But it will be hard to leave behind a lot of the love.”

You get older and have no patience for wasting time. Achievement or not disappointing someone is for when you are younger. Doing for others is terrific, wonderful, but doing for self becomes important. But it will be hard to leave behind a lot of the love. Along with love, there was steep, significant learning. Salerno-Sonnenberg admits she had no idea what she was getting into when the strong, instantaneous, joyful chemistry she felt for the orchestra caused her to accept directorship. “I knew there was this wonderful, vibrant orchestra with whom I clicked. It had to happen,” she says. The gains she made as a musician could only have happened as a member of an ensemble, not as a soloist. “Musically, it forced me to be a more acute listener. I was always a good listener but you get lazy. A second thing: I had to have more respect for what was written on the page. As a soloist, you have more freedom. You can make a dotted eighth note what you want it to be: in fact, you should. But in an ensemble, it’s about more than me, there were aspects of blending I learned.”

The administrative challenges were many and remain even as she leaves: how to work with union musicians, using diplomacy and patience with a board of directors — even one she says is “phenomenal and put this orchestra on the trajectory to success and acknowledgement.”

Her greatest satisfaction comes from being proven right about the ensemble. “I was hell-bent on taking them on tour because I think NCCO is taken for granted in the Bay Area. I knew when we walked onstage in other parts of the country, they’d go crazy and that’s exactly what happened.”

Under her leadership, NCCO expanded the string orchestra repertoire with eight new works under the Featured Composer program. Three national tours brought critical acclaim along with strong notices for three live recordings on Nadja’s NSS music label. Partnerships with Bay Area arts organizations including San Francisco Opera, San Francisco Girls Chorus, and Chanticleer, among others, and special projects featuring renowned guest artists raised the orchestra’s profile at home and nationwide.

“New Century had been performing a variety of music for years, so I did not bring that to them as something new,” she says. “What I wanted from early on is that the orchestra not get pigeonholed. I heard ‘What is our brand?’ at board retreats — and as a musician, I almost resented that. This is not a Baroque, Romantic, [or other period-specific] orchestra. It is an orchestra that can play anything. That was important to me.”

The achievements in part answer the most complex questions about the impact Salerno-Sonnenberg had on NCCO, and determine the ways in which the orchestra is preparing for her successor. Fellow musicians across the board speak to her role in challenging and elevating their own and the orchestra’s quality and visibility.

“The first time I worked with New Century I did Britten’s Les Illuminations (The Illuminations) and Nadja was not yet the conductor/principal violin,” writes soprano Melody Moore in an email. “When Nadja came onto the scene and I was asked to guest, I thought, we must do those again with her at the helm — it will rock. And boy, did it. Nadja is so very passionate and impeccable; yet, she’s approachable. I have loved working with her, being guided by her and watching this journey.”

Pianist Anne-Marie McDermott will appear with Moore and other guest artists in the all-Gershwin program May 20 that is part of the week-long festival to celebrate NCCO’s 25th Anniversary and Salerno-Sonnenberg’s eight-season leadership. McDermott says the orchestra’s music-making under Salerno-Sonnenberg shows increased flexibility and fluidity. “She has imbued the ensemble with a sense of vitality and joy and intensity. They play as one now more than ever,” says McDermott.

Perhaps because Harms sat within arm’s reach of the dynamic violinist, she has felt most profoundly the effects of Salerno-Sonnenberg’s razor-sharp focus, extreme preparation standards, and “when it’s showtime, it’s showtime” mentality. “I would have to say the increase in the level of excitement of our performances is just astounding,” says Harms. “The group now has an edge, an “on fire, taking the notes off the page and making them fly” style that is defined and unique. With Nadja, we don't just play the notes, we paint them.” Working with composers on premieres written for the orchestra has provided especially unforgettable, pinnacle experiences, she adds.

But nothing, other than perhaps memories of playing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” at AT&T Park, compares to an evening they spent together. “I was a percussionist in high school and played the trap set as well as all of the percussion instruments,” says Harms. “We were both at Aspen one summer, and we had been discussing the rep for her first year as our NCCO music director. She was staying at a stunning house and, wouldn't you know, the owner of the house had a drum set in the basement. Well, what else was there for us to do, but enjoy an evening of banging the heck out of it? We had a ball for the next two hours. I actually have a video of me teaching her to play. She was bright-eyed, like a kid in a candy shop.”

Executive Director Philip Wilder says the appointment of Daniel Hope as artistic partner begins a three-year period during which the search for a permanent Music Director will be conducted. Hope will conduct and invite guest concertmasters to lead the orchestra. Wilder says they plan to be thorough, diligent, and to “take as much time as needed to find the perfect fit.” McDermott says because Salerno-Sonnenberg is irreplaceable, it will take someone special to step into the position. “The most important qualities in a music director should be [having the] highest possible standards for ensemble playing, great passion for the music, strict rehearsal protocol, and the ability to speak about music in an inspiring way.” Harms adds her wish list for music director and the orchestra’s future: “Showing 100 percent respect to the players, giving each of us chances to shine now and then, being able to be one of us, yet a leader at the same time. I also hope we get to tour more.”

All of which lines up nicely, even precisely, with Salerno-Sonnenberg’s hopes for the ensemble. “We are known to be unique and we worked very hard to get there. They didn’t have a strong sense of self-worth when I came on. Hopefully, whoever comes on will continue on that path. It’s a badge of pride they should carry with them. That is what a new music director should know about New Century.”

As for teaching, she says any professional has the information, but imagination and commitment to go above the job description identify an exceptional instructor. “You must be inspirational and you have to be inspired. If a kid has a problem, you have to identify it, imagine how to get your idea through to them, then inspire them to work on it because otherwise, what’s the point?”