When Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross won the Academy Award for their score to The Social Network in 2011, it was another disruption in the long evolution of a relatively new art form. Here were the industrial rock stars of Nine Inch Nails taking home film music’s biggest prize for a series of pulsing electronica tracks that weren’t even written to picture. (Instead, they created a batch of musical “swatches” and handed them over to the film editor to be applied freely.) Their win offended traditionalists who prefer symphonic orchestras and scores tailored to a film’s edit like a bespoke suit — but it was hard to argue that their music didn’t perfectly suit David Fincher’s digital-era Citizen Kane story of Mark Zuckerberg with its quicksilver Aaron Sorkin dialogue.

That was 10 years ago — more than a tenth of the 90 years film music has existed since the dawn of talkies — and meanwhile Reznor and Ross have become two of the most in-demand composers in Hollywood. This year they’re up for not one, but two Best Original Score Oscars, a sign of their haute dominance as well as the ever-changing definition of a great (or effective) score.

It’s also a sign of their own evolution. Reznor and Ross are nominated for their throwback, jazzy score for Mank, which traffics in both the big-band sound of the film’s 1940s period as well as the style of Bernard Herrmann — composer for the original Citizen Kane — which Mank’s protagonist (played by Gary Oldman) spends the course of Fincher’s new film screenwriting. It’s a significant departure for the typically modern, electronically processed rockers, and cynics might see the music branch’s nomination as a statement of shock that these two could write this score, but it’s nice to hear them stretching and growing all the same.

The duo’s other nod is for Pixar’s Soul, which found them in very new storytelling territory — subject matter their kids can watch for once, as Reznor likes to joke — but also writing music that is idiosyncratically major-key and hopeful. “We still are filled with insecurity and self-questioning,” Reznor told me earlier this year, but “we wanted to make sure we could give them comfort to know, hey, we can make music that isn’t just bowel churning stuff to feel uncomfortable about.”

Their Soul score is, stylistically, very much in the Social Network vein of hypnotic, futuristic mood pieces (which is undoubtedly why director Pete Docter hired them instead of his usual, more old-school composers like Michael Giacchino and Randy Newman). The approach works well for the film’s ethereal beyond, a tech-heavy realm of both the afterlife and before-life — the same musicians who defined the cinematic story of Facebook now defining an Apple-like spiritual plane.

But the heart and, yes, soul of Pixar’s movie about a Black jazz pianist (voiced by Jamie Foxx) is Jon Batiste, whose contribution was, fortunately, deemed eligible by the music branch despite being credited differently from Reznor and Ross in the film. The Grammy-nominated recording artist, probably best known as Stephen Colbert’s Late Show bandleader, lent the film’s hero his literal piano-playing fingers as well as the many jazz pieces that protagonist Joe Gardner performs in his time on earth.

The two musical worlds collide in a cue called “Epiphany,” where Joe plinks out a bittersweet tune on an upright piano that encapsulates his newfound revelation about what makes life meaningful — Batiste performing a composition by Reznor and Ross. (Docter told me that the first time he heard it, “I just started weeping, because it felt so much of what we were trying to say ... Sorrow, bittersweet, but beautiful and thankful and kind of grateful.”)

Gamblers have their money on Soul winning the Oscar, as it did the Golden Globe. It wouldn’t be a bad choice at all to honor such an emotional, eclectic score, for a movie so centrally about music — and to give a Black composer an Oscar for only the second time in the film academy’s history. (Herbie Hancock is the first and only Black composer to win best score, for Round Midnight back in 1987.)

Terence Blanchard, veteran jazz trumpeter and Spike Lee’s right-hand composer, finally received his first Oscar nomination in 2019 for BlacKkKlansman. (He lost, ironically, to a film called Black Panther scored by a white guy.) He’s nominated again this year for Lee’s Vietnam vet, treasure-hunt adventure, Da Five Bloods. Lee always prefers an overt, operatic approach — whether it’s for a contemporary crime thriller or a period war movie — and Blanchard poured all of his past scoring experiences into a richly melodic score that honors the magnitude and “majesty” of the unsung Black soldiers who fought in Vietnam. There’s a highly mannered, self-aware nature to Lee’s filmmaking style that thrills some audiences but leaves others (including myself) a little frustrated, and Blanchard’s simpatico score for Da Five Bloods may be a little too much for voters. But it might also just be the most ambitious — and best — film score he’s ever written.

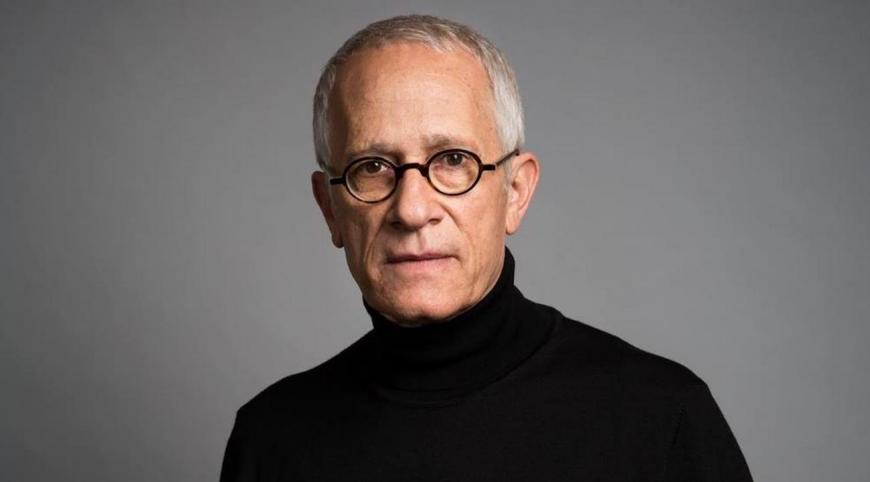

If there’s any narrative to this year’s crop of nominees, it’s the crossroads between old and new, between an all-white history and the belated emergence of the alternative, between computer-age rock stars and classically trained veterans. The latter’s lone representative is James Newton Howard, who was at one time the new-kid usurper to elders like John Williams and Jerry Goldsmith, but now, at 69, symbolizes the old guard. Of course, electronics were as much a part of Howard’s formation as they were for Trent Reznor. Howard, too, began his career playing in rock bands, but he was first and foremost a trained pianist who grew up on a diet of classical music and the symphonic, leitmotif-heavy approach of composers like Williams and Goldsmith (his hero). Howard has admirably carried forward the Goldsmith tradition on everything from The Fugitive in 1992 to Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life in 2019.

News of the World, his nominated score, is the most traditional of the bunch — which is anything but an insult. Paul Greengrass’s classical Western, starring Tom Hanks as a weary news reader in post- Civil War America, is complemented by a hymn-like, hummable main theme, rambling travel music, and cleanly orchestrated, kinetic set pieces. Howard is a defiantly orthodox film composer (except when he’s not), and he relies on the power of a good tune and the heft of a traditional orchestra, developing a symphonic narrative in parallel to the story beats of the film.

The slightly unique players in the News score include a viola da gamba, cello d’amore, and gut string violin — part of Greengrass’ concept of having a “broken consort” traveling around in the wreckage of the war. It’s beautiful, deeply moving music that elevates the film and improves on every listen — and it might be too normal for Oscar voters to pay any mind. Howard has been nominated for nine Oscars since 1992, without a single victory. (If I had the power to hand out Oscars, I would have awarded him for The Fugitive and M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs, among others.) Howard is in the good company of composers like Thomas Newman: empty-handed veterans who deserve multiple Oscars.

Finally, at the other end of the career spectrum is Emile Mosseri, the 35-year-old (relative) newcomer who received his first Oscar nomination for Minari. Mosseri is a film composer who splits the difference on many of these divides: He studied film scoring at Berklee College of Music, but began his professional life in an indie band; he has a penchant for melody and elegant, romantic orchestration, but his scores are typically constructed more like a collection of wordless songs or groove-based mood pieces (as opposed to a through-composed, symphonic approach). This songlike style is very much en vogue right now, and while it has detractors, it can work like gangbusters in film. It also resurrects a lyricism that’s been out of fashion for far too long in mainstream American movies.

Another new trend — one that Reznor and Ross have participated in — is composers writing a lot of the score before the film is even shot, which is what Mosseri did on Minari. Based on Lee Isaac Chung’s script and conversations he had with the writer-director, Mosseri made a series of demos that attempted to evoke the fundamental idea of childhood memory and nostalgia, along with other more specific “scenes.” Chung responded to these pieces (often performed by a bandlike ensemble of guitar, piano, and Mosseri’s voice, with a measure of processing) so strongly that they shaped how he made his film, including the staging of a montage in slow motion in order to complement one of Mosseri’s tracks. (These rough sketches were later developed and finessed in postproduction, with strings and woodwinds added.)

Joining the likes of composer Nicholas Britell with director Barry Jenkins (If Beale Street Could Talk) and Justin Hurwitz with Damien Chazelle (First Man), Mosseri and Chung’s method of pre-scoring a film gives the music a special prominence and power, baking it directly into the cake as opposed to icing it at the end. Chung’s film is very naturalistic and it’s about rather quotidian events, but with Mosseri’s dreamy, wobbly, achingly tuneful music, he leaned into the poetry of the story — the romance of it — which is arguably one of the reasons audiences have responded to it so emotionally. For my money, the Minari score is the best of the bunch.