At New York City Opera’s (NYCO) 1986 premiere of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, Manhattan audiences witnessed an early instance of what would quickly become a subgenre. In investigating a figure so fresh in their viewers’ consciousness — Malcolm X had died only two decades earlier — composer Anthony Davis, librettist Thulani Davis, and storyboarder Christopher Davis (all related) began a trend of weaving recent realities into operatic tales. No longer could spectators divorce their lives from the plot they saw onstage; in this case, most of them had lived through it.

After its debut and 1989 recording, X lay dormant for more than three decades, save for a 2006 weekend at the now-extinct Oakland Opera Theater and an abridged 2010 concert performance from NYCO (only a few years before that company’s untimely bankruptcy).

But for X, the third revival effort would be more than a hasty one-off. As operatic institutions belatedly reckon with their overwhelmingly white pasts and seek to mount more works by Black composers, five major U.S. opera companies have jointly commissioned an X production from Tony Award-nominated director Robert O’Hara. The staging debuted with a revised score in Detroit in 2022 and stopped in Omaha that same year before making its way to New York’s Metropolitan Opera for a fall 2023 run that ended Dec. 2. O’Hara’s production is destined for Seattle in 2024 and Chicago at a date to be announced.

At that Met closing-night performance, X proved its potential as a house standard. The piece is utterly compelling, a master class in the show-don’t-tell model that so many modern operas fail to achieve. The Davis trio trace Malcolm X’s story through a series of chronological vignettes, presented plainly and without judgment. It’s a model that hinges on Malcolm X’s radical transformations — from boy to man to activist and through his hajj and subsequent enlightenment — but still leaves the audience to evaluate the title character’s development. And it does so deliberately and matter-of-factly, forgoing fast action and plot twists in favor of luxuriant scenes that extend individual events into fully formed musical movements.

The pace largely owes to the way Anthony Davis sets Thulani Davis’s fabulous libretto, and that synthesis is one of the show’s strongest facets. In X, for every note a vocalist sings, the orchestra matches him or her tenfold — the vocal score is 500-odd pages, even though the libretto contains a mere 20 pages of text. In slow sections where the prose flows freely, the music matches, setting punishingly long vocal phrases over colorful orchestral filigree. In faster moments, tidy, unforced couplets reign, punctuated by emphatic pauses which allow steady bass-heavy grooves to shine through.

Those grooves put Anthony Davis’s score in the realm of jazz, perhaps the most noticeable of X’s many musical influences. Sometimes, the references are plain, obvious, and perfectly crafted, as in the straight-ahead honky-tonk swing number that welcomes a young Malcolm X to Boston. But more often, shuffles on the drum kit anchor rapid mixed-meter changes, chords wander into clusters, and melodies gain spiky angles that both undergird and drive the drama. And improvised solos abound — conceived for Davis’s octet Episteme, who here played with acute instinct among the Met Orchestra’s ranks under conductor Kazem Abdullah.

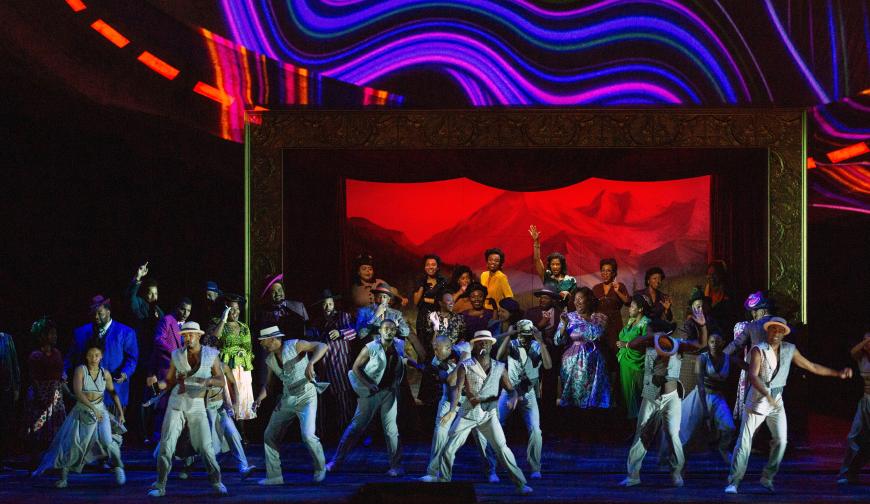

In O’Hara’s production, the audience first sees Malcolm X with his back turned, silhouetted in a power pose below an oculus-like ring. He’s surrounded by a mighty cadre of dancers who one at a time break their frozen stances with jagged, outstretched movements that almost seem to portend tragedy — there’s nothing to give away, as the audience surely knows how the story ends. The choreography by Rickey Tripp takes a modern approach, elegant but expressive; when the dance corps moves in unison, it’s in a perfect synchrony that still allows for individual flair.

A fully grown Malcolm X doesn’t speak until nearly an hour later, in the final aria of the first act. Baritone Will Liverman inflected those first stanzas, delivered from a prison interrogation room, with spite and indignance, reinforced by an unsettling preamble of clarinet multiphonics (here, a jarring noise produced by simultaneously singing and blowing into the instrument). As Malcolm X the orator, Liverman continued to lean into those snarls, his rich, booming tone conveying defiance and action. But when Malcolm X leaves for his pilgrimage to Mecca — and when he returns enlightened — Liverman smoothed those edges, highlighting his character’s transformation in voice and affect alike.

Soprano Leah Hawkins brought urgency to the role of Malcolm X’s mother, Louise, her breaths theatrically audible, as if panting under an oppressive force. As Macolm X’s wife, Betty Shabazz (whom Thulani Davis interviewed while writing the libretto), Hawkins’s tone turned from disillusionment to concern. Mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis and bass-baritone Michael Sumuel excelled as Malcolm X’s siblings — Sumuel’s resonant voice was the only one to dwarf Liverman’s onstage. And tenor Victor Ryan Robertson gave jazzy verve to Anthony Davis’s take on dancehall swing as Street, the fictional character who situates a young Macolm X in his new Boston community; as the prophet Elijah Muhammad, Robertson’s light, piercing voice took on austerity and gravitas.

But X was also the choir’s show. Davis’s choral writing is intensely polyphonic, full of vamping modules that build and stack into walls of sound. Even as the text-heavy melodies pile up, Davis weaves them with astonishing transparency, the chatter of consonants never overbalancing new text or musical material. Decked in Afrofuturist-inspired costumes by Dede Ayite that played more with shape than color, a pared-down Met Chorus executed the fiendishly difficult and highly involved score with clarity of pitch and phrasing rare from the 80-strong mobs that the house usually employs.

The Met’s newer offerings (broadly defined) usually tend musically conservative, even if they push boundaries in other areas — think of the syrup of Kevin Puts’s The Hours or Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking. With high sales and broad critical acclaim, X proves that the Met can indeed find success in exploring modern musical idioms that are fundamentally their own, no comparisons required.

Earlier that same December day, the Met showed its prowess with one of those newer operas which mines older idioms. The music of Daniel Catán’s 1996 Florencia en el Amazonas, the first Spanish-language opera the Met has mounted in nearly a century, is often drop-dead gorgeous, but it’s just not that original. On the voice, the score evokes Puccini in its virtuosic attention to phrasal direction and peak. For the orchestra, harmonic extensions and dreamy flutters come straight from the book of Maurice Ravel. Sure, Catán adds a healthy dose of percussion that hadn’t yet made it to early 20th-century France — but if Ravel had had access to a marimba, Florencia shows how he would have made it sound.

Still, derivative as the score may be, it complements the opera’s fantastical storyline perfectly. Marcela Fuentes-Berain’s scenario and libretto draw heavily on the magical realism of her mentor, literary giant Gabriel García Márquez. What results is an ensemble drama of passion, love, and tragedy, rooted in but not strictly confined to reality — and a worthy addition to the historical legion of operas about opera.

Most productions of Florencia mount a full-sized barge on their stages as the steamship El Dorado cruises down the Amazon to Manaus, Brazil. At first, Tony Award-winning director Mary Zimmerman’s decision not to do so appears as a cost-cutting measure. Zimmerman instead creates the ship’s space with cleverly placed banisters and foghorns, set against greenery-covered walls that curve to emulate the Amazon River’s mouth. It’s an economical choice, one that lends more abstract expression to the ship itself — when a storm briefly besieges the El Dorado, the boat’s tottering comes in the form of striking choreography by Alex Sanchez that whips the outer banisters into organized chaos.

Zimmerman’s production also puts the singers on the same visual level as the river they traverse, allowing el Amazonas to show the wildlife it houses. More than any other aspect of the production, it was the lifelike puppets, by set designer Riccardo Hernández, that were jaw-dropping — not quite as gaunt or elaborate as Julie Taymor’s famed Broadway Lion King marionettes, but the comparison stands. A school of silvery piranhas wobbled atop actors’ headpieces. Bright-pink water lilies drifted along, pulled on broomsticks by puppeteers whose matching outfits almost evoked Pokémon. A menacing crocodile made several appearances, its sectioned body melding into the stage floor as if floating on either side of the surface.

As the singer Florencia Grimaldi, incognito aboard the El Dorado to reclaim the lost love that began her operatic career, soprano Ailyn Pérez sang with yearning fervor, her crescendos blossoming from near nothing to full, resplendent fortissimos. Soprano Gabriella Reyes played Rosalba, the journalist researching the cloistered Grimaldi’s biography, with appropriate zeal and wit — her pained cries as piranhas devoured her research notes hit a little too close to home. As Rosalba finds first love in a duet with Arcadio, the tenor Mario Chang, Reyes’s voice gained a youthful sparkle against Chang’s creamy tone. Mezzo-soprano Nancy Fabiola Herrera and baritone Michael Chioldi gave the distant couple Paula and Alvaro acerbic humor, and bass-baritone Greer Grimsley thundered through the captain’s lines.

But perhaps the most compelling character was the mysterious first mate, Riolobo, here played by baritone Mattia Olivieri. Riolobo is the only principal character who is squarely of the Amazon, and costume designer Ana Kuzmanić outfitted him as such; his burlap top, head wrap, and dangly earrings contrasted with the flowy dresses and linen suits of the ship’s guests, highlighting Florencia’s colonial atmosphere. (After all, how did opera get to Latin America in the first place?) Riolobo is the all-knower, the character who introduces the cast in the prologue, the one who continuously breaks the fourth wall, sharing inside jokes with the audience, a twinkle in his eye. He is the character that makes the opera, and Olivieri lent the role rambunctious comedy and a sweet voice, always carefully caressed, even at its loudest.

Yes, the vocalists sounded tremendous, when they were audible over the orchestra — Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s enthusiastic baton threatened to cover the singers at most mid-to-loud dynamics, an annoying but endemic problem from one of North America’s highest-paid music directors. Still, one can’t complain about the orchestra’s realization of Catán’s brilliant color palette, flutes fluttering, percussion ambling, a piercing trumpet leading the loud sections, as in Puccini’s late oeuvre. A few intonation issues were cringeworthy, but in a day with two strenuous shows, who could possibly blame the players?