There aren’t many double concertos in the repertoire beyond the 18th century; apparently there hasn’t been much of a crying need for them. I don’t know why, but maybe star soloists prefer to work alone in the spotlight in front of an orchestra?

In any case, Brahms’s contribution to this format is by far the best known — and to my ears, it’s his best concerto of all. That’s a minority opinion, for sure, and advocates of the Violin Concerto and two piano concertos will beg to differ. But the melodic material of the Double Concerto in A Minor, Op. 102 — particularly the soulful theme in the second movement that the violin and cello play in unison — and the conversations that the two soloists have with each other do more than anything the other Brahms concertos have to offer.

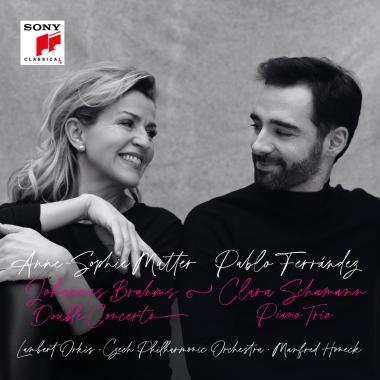

It’s the conversational aspect of the Double Concerto that the well-established violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and the up-and-coming Spanish cellist Pablo Ferrández excel at in their new recording from Sony Classical. Ferrández opens the first movement with a surge of passionate involvement, and Mutter soon joins him in a high-energy duet. Later on, Ferrández applies a soft, feathery touch, with Mutter trilling like a bird, and they carry on musical dialogues that sound like real conversations

In the magical second movement theme, alas, the two aren’t as convincing. They heave, they whisper, and they lose the thread of the line. The finale lifts off like a true scherzo but soon bogs down in spots, and the tone qualities of both turn somewhat abrasive as they press harder on the strings. Manfred Honeck and the Czech Philharmonic accompany the pair and fill in the orchestral portions with thick, heavy-set textures at moderately slow tempos.

While this recording has its virtues, particularly in the first movement, for a full dose of Double Concerto eloquence, turn to the Isaac Stern/Leonard Rose recording with Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic from the mid-1950s (also Sony) — tubby mono sound and all.

Mutter and Ferrández do provide an imaginative coupling — the Piano Trio in G Minor by Brahms’s dear friend (and probable crush) Clara Schumann, with pianist Lambert Orkis joining the string duo. The opening movement almost sounds as if Brahms had written it, but since he was only 13 when Schumann composed it in 1846, there seems to be little doubt in this case as to who influenced whom.

However, Schumann ventures into different spheres in the next two short movements. The second movement begins playfully and stays that way until we get to a lyrical Trio section, and the third has a piano introduction that seems to evoke Chopin in a nocturnal mood before the two string players encounter some cut-and-thrust passages. The finale opens with the most striking theme in the piece and briefly offers up a fugue.

The Clara Schumann Piano Trio has been recorded several times before, but it hadn’t really received its due until recently when women composers became more represented on concert programs. But it doesn’t need that excuse. For its quality of invention alone, the piece deserves an equal spot in the literature alongside the trios of Johannes Brahms and Robert Schumann.