This has been an unusual summer for Gustavo Dudamel. Besides the obvious reason, or perhaps because of it, Dudamel has been spending a lot of time at the Hollywood Bowl — four weeks of programming instead of the usual two or three during the main summer season, plus a tacked-on Mozart concert near the end of September.

Meanwhile, the Bowl’s season of diversity marches on. It remains to be seen whether the sudden influx of music by Black and female composers into general concert life will stick, or deserves to stick, when judged on the music’s own merits after getting in the door. What we do know is that there is a plethora of irresistible music by Latin-American composers that also doesn’t get programmed often. And it has long been obvious that Dudamel is their ideal current interpreter; he gets it, he feels the pull and swing of the rhythms, and sweeps the Los Angeles Philharmonic along with him.

So on Tuesday night (Aug. 24) it was the Latin American composers’ turn to shine at the Bowl — at least it was in the first half, with the second half turned over to a permanent Russian resident of the Bowl, by the name of Tchaikovsky.

First up was just a wisp of Brazil’s Heitor Villa-Lobos, the brief Preludio from his Bachianias Brasileiras No. 4. The whole cycle of nine Bachianas Brasileiras is something that Dudamel and this orchestra ought to explore in depth, and the Preludio from No. 4 kind of gives you the general idea of what the concept is about — gorgeous, minor-key, post-Romantic music infused with forms and rhetoric derived from the language of J.S. Bach, though without the overt Brazilian element of other parts of the cycle. Gustavo and the LA Phil strings played it slowly, passionately, and with as lush a texture as they could manage. To steal a word from a late music critic of yore without malicious intent, you could almost call it “Bach-maninoff.”

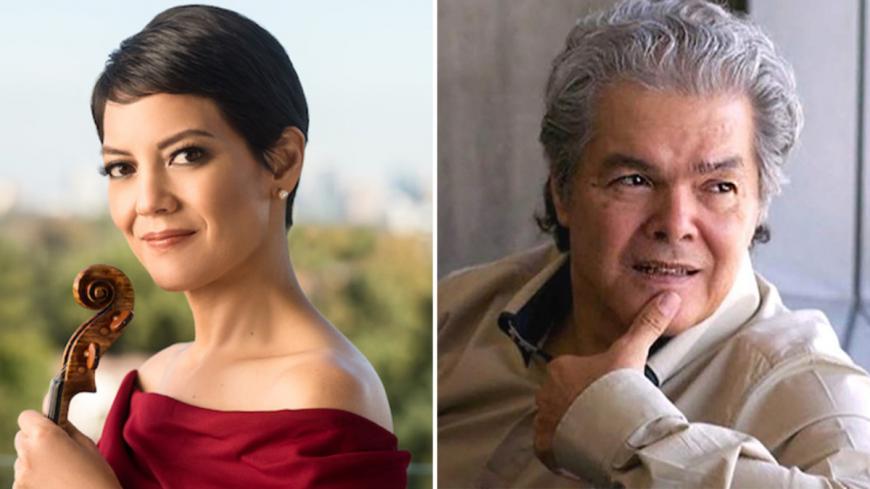

I wondered why the orchestra did not play the entire four-movement Villa-Lobos piece instead of limiting it to an excerpt less than four minutes in length. The next piece offered a clue; it was the world premiere performance of a newly commissioned violin concerto titled Fandango by a Dudamel favorite, Mexico’s Arturo Márquez. It’s a big, formal, three-movement, essentially Romantic concerto with sporadic Latin grooves, written during the pandemic for violinist Anne Akiko Meyers (who was on hand as soloist) and lasting nearly 33 minutes — thus probably crowding out the possibility of performing and preparing on short rehearsal time the full Villa-Lobos piece.

It was the young Dudamel who, in the midst of his break-out years, also put the now-70-year-old Márquez on the international map with his championing and recording of Danzón No. 2 — and if you know that piece, along with Conga del fuego, you’ll know much of what to expect from Fandango. After a tempestuous opening with a passionate solo violin line, the Afro-Cuban clavé rhythm surfaces and we go through a series of dances and developments with connecting interludes and not a whole lot of difference between the three movements upon a first listen. Fandango sometimes seems too long for the good of its material, but with Dudamel giving the rhythms a sharp push and Meyers maintaining her poise particularly when the third movement cranks up the level of virtuosity, the piece made an invigorating impression outdoors.

The appearance of the words “Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5” on a program often telegraphs the onset of routine for bored symphony orchestras, but this time, there was a compelling subtext that had to influence the performance. It was in this very piece, in this very same Hollywood Bowl, that Dudamel made his North American debut in 2005 with the LA Phil.

Those who expected an electrifying reprise of his debut performance got it. Those who wondered if he could improve upon his sometimes-lugubriously-paced, so-so 2008 recording of Tchaikovsky No. 5 with the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon) would have been heartened by the faster tempos in every movement, the crackling climaxes, the greater attention to details in phrasing, rhythm and color that give music life and flow. Once Gustavo and the Phil sailed through the Allegro vivace signpost of the finale, the thing just went in a furious rush up to and after the penultimate march. If the 2005 performance ended anything like this, no wonder that events just snowballed from there for Dudamel.