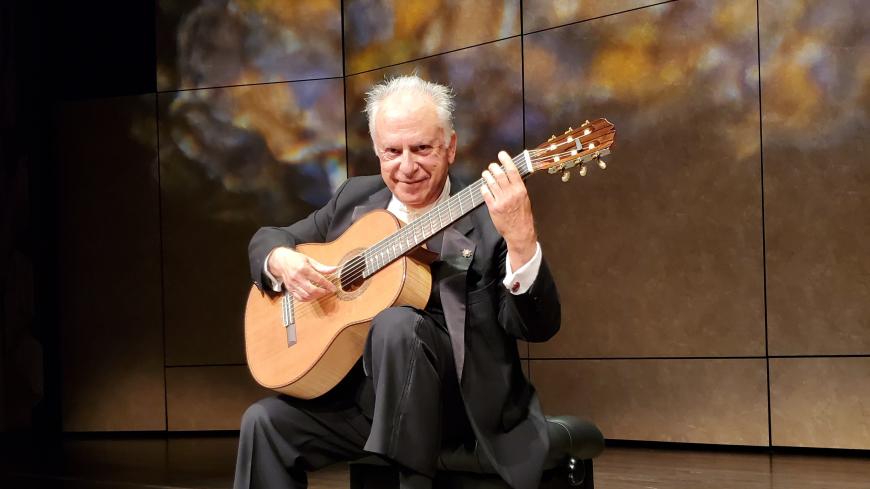

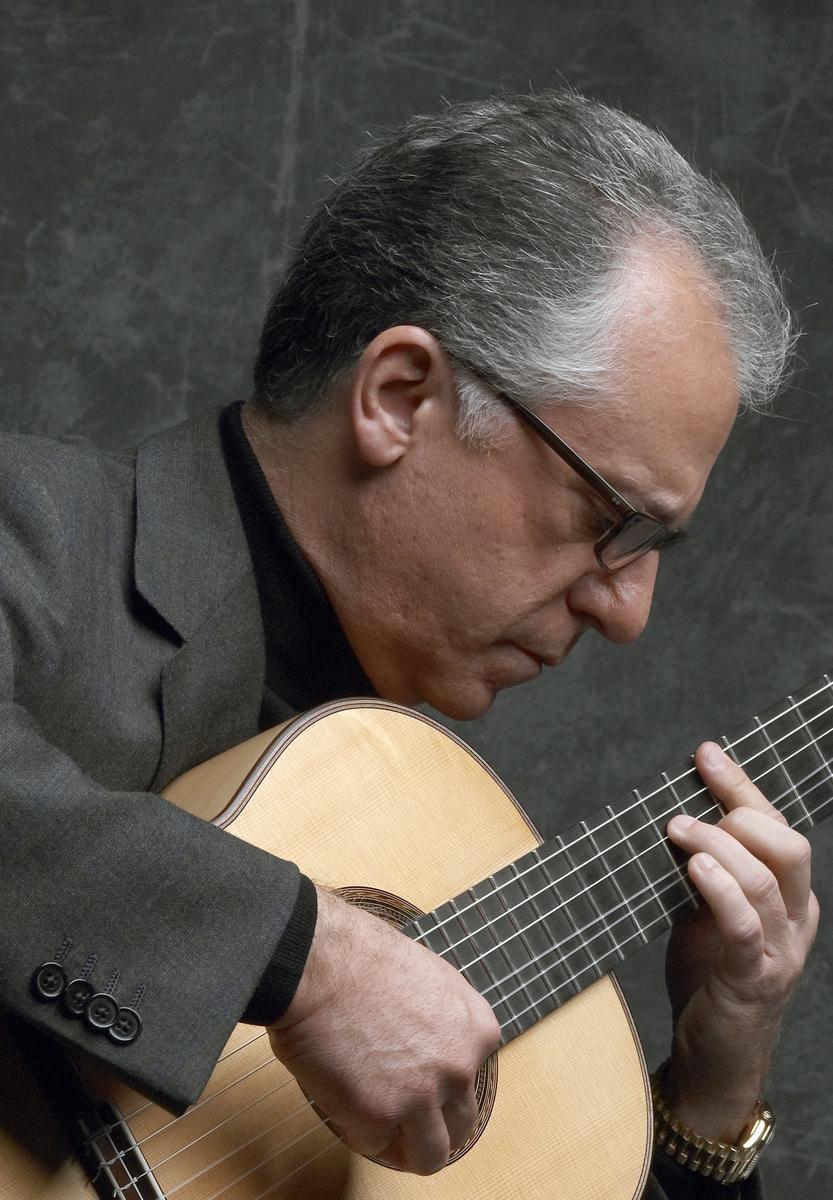

The legendary classical guitarist Pepe Romero joked to his audience on Saturday evening at Herbst Theatre that he began his study of music 80 years ago, when his father played J.S. Bach for him just minutes after he was born. Celedonio Romero, in addition to being a well-known soloist and founder of the Romero Guitar Quartet, was the most influential guitar teacher of the 20th century.

Pepe’s years of study were evident in his deeply moving recital for the Omni Foundation and San Francisco Performances. It was almost business as usual for this man who gave his first San Francisco recital in 1960, at age 16, in the Masonic Temple.

The concert was an exploration of seven centuries of Spanish guitar music and began with Luys Milán’s Fantasía No. 16. Romero’s performance invited the audience into an intimate world characterized by quiet reflection and the sharing of deeply personal emotions. The composition conjures up an improvisation; in his influential 1536 book El Maestro, Milan emphasizes the importance of varying the tempo according to the style. Romero played with great elegance and dedicated the performance to the memory of his father, who loved this work.

Gaspar Sanz’s Instrucción de música sobre la guitarra española was a popular collection of dances for guitar in the 17th century and remained influential long after. Manuel de Falla utilized Sanz’s themes in his 1923 work El retablo de maese Pedro, and Joaquín Rodrigo did the same in his 1954 guitar concerto Fantasía para un gentilhombre. Romero published his own selection of Sanz’s music as Danzas Españolas and played it here with gorgeous and intricate ornamentation.

Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos’s Five Preludes were the one exception to the recital’s Spanish theme. Romero told the audience that when he and his guitar virtuoso brothers were children, his father insisted they have completely different repertoire to avoid competition within the family. Much to Pepe’s chagrin, his older brother Celin got the Villa-Lobos Preludes.

Happily, in the ensuing 50 years, they have come to an agreement that Pepe can now play the music, and his love and admiration for the Villa-Lobos shone forth in every note. Romero is known for his soulful tone, and the depth of feeling in his performance of Prelude No. 1 (“Lyric Melody”) was profound. In Prelude No. 2 (“Homage to the Rascals of Rio”), Romero’s flexibility of rhythm was impishly playful, while in Prelude No. 3 (“Homage to Bach”), he took a profoundly slow tempo reminiscent of the Baroque composer’s sarabandes.

Romero played Prelude No. 4 (“Homage to the Brazilian Indians”) with a wild abandon that evoked an untamed jungle wilderness, and in Prelude No. 5 (“Homage to Brazilian Social Life”), he gave us a joyous, urbane portrait of the musical nightlife of Rio de Janeiro. Collectively, the Five Preludes were the high point of an outstanding recital and presented a huge variety of feeling that evoked the atmosphere, temperament, and spirit of Brazil.

Arroyos de la Alhambra, by Ángel Barrios, Serenata Española by Joaquín Malats, Spanish Dance No. 5 (“Andaluza”) by Enrique Granados, Nocturno by Federico Moreno Torroba, Capricho árabe by Francisco Tárrega, and Torre Bermeja by Isaac Albéniz represented the Spanish guitar repertoire of the 19th and 20th centuries. Barrios and Tárrega were guitarist-composers; and Malats, Granados, and Albéniz were pianists who were inspired by the sound of the guitar and composed music that guitarists have made their own; and Torroba was a well-known composer who was inspired to write directly for the guitar by Andrés Segovia. Romero played all these pieces like someone who has the music of Spain in his blood and uses it to express the depths of his soul.

The emotional climax of the evening was a performance of Celedonio Romero’s Fantasía Cubana. The composer’s sympathy with Spain’s Republican government during the Spanish Civil War had an adverse effect on his career when Franco’s forces were victorious, but in 1958, the elder Romero was able to immigrate to the United States. Fantasía Cubana, inspired by the folklore of Cuba, is full of delightful guitaristic effects: rasgueado (flamenco strumming style), punteado (plucking), ponticello (playing close to the bridge), tastiera (plucking over the fingerboard), extended left hand-only slurs, and more. Pepe Romero played with an obvious love for all his father gave to him and all who love the guitar. The audience was enraptured.