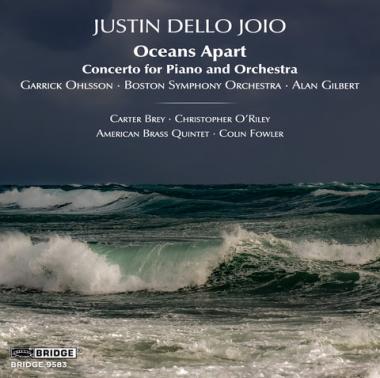

It’s no military secret that we live in turbulent times, and the world outside the ivory towers of classical music has affected Justin Dello Joio’s long-gestating new piano concerto, Oceans Apart. Dello Joio, 68, the heir to several generations of musical Dello Joios, suggests that the title could have several meanings: the political polarization of the nation, misinformation that drives people further apart, the distance between current composers of concert music and their audiences, and of course, climate change. All of which may be plausible, but the overwhelming impression you get from this 19-minute, single-movement, predominantly tonal piano concerto is of ocean waves — per the cover art for the piece’s new recording.

The whole thing is spectacularly played by pianist Garrick Ohlsson and the Boston Symphony under Alan Gilbert in a live concert setting (with the applause left in). Ohlsson has been a Dello Joio advocate of long standing. Having recorded Dello Joio’s Two Concert Etudes and Piano Sonata back in 2006, he was promised a piano concerto by the grateful composer via a BSO commission, but it took several years of work to make it finally happen in 2023.

Oceans Apart starts with a pair of prepared-piano thunks, followed by rippling, rolling waves of chromatic scales from the piano, whooshes from the cymbals, rustling strings, simulated sounds of the wind. It’s like a second or third cousin of Become Ocean, John Luther Adams’s orchestral soundscape, but much more concise, building to a crunch about 17 minutes into the fray before finally descending into the gloom of the wind and various dim orchestral growls. Dello Joio’s piece requires monster technique, which Ohlsson has to burn — and his clearly articulated playing revels in the score’s brilliant splashes of color.

Filling out the recording with more Dello Joio, New York Philharmonic principal cellist Carter Brey and pianist Christopher O’Riley (of NPR and Radiohead transcription fame) play Due per due, which consists of “Elegia: To an Old Musician” — a doleful, lyrical meditation that also opens with a thunk — and a “Moto perpetuo” that maintains its promised momentum only in spurts. Finally, Blue and Gold Music, for the spangled combination of the American Brass Quintet and organist Colin Fowler, makes a grand, festive impression with plenty of satisfyingly deep bass from the organ and some humorous touches from the brass.