This opera shouldn’t have worked. The premise was too ridiculous: that campiest of horror novels, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, superimposed over a classic of Greek tragedy, Euripides’s The Bacchae. Yet composer John Corigliano and librettist Mark Adamo have defied all odds to create a disturbing parable that ranks among the finest American operas in recent memory.

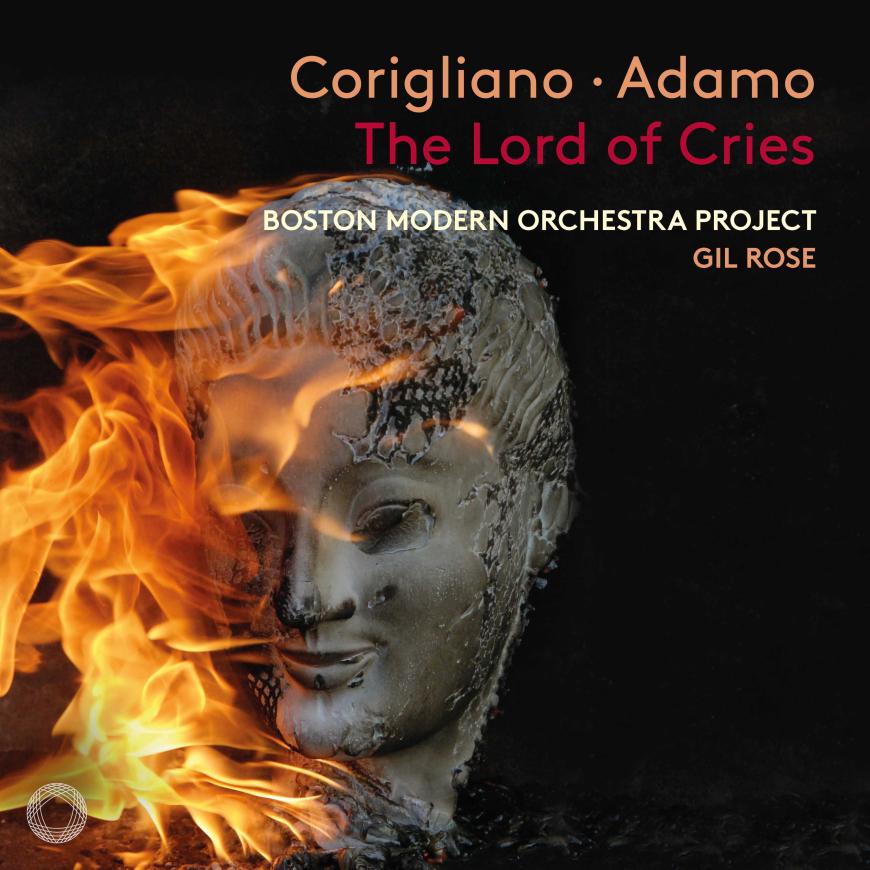

Recorded for Pentatone in 2022 by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP), The Lord of Cries had its staged premiere a year prior in Santa Fe. That’s a full three decades after Corigliano’s first opera, The Ghosts of Versailles, opened at the Metropolitan Opera. The unjustified lambasting of that earlier stage work, as well as its 10-year gestation period, likely turned the composer off the art form. His withdrawal was a supreme disappointment to those of us who recognized the genius of Ghosts in all its extravagant, neoclassical glory. But a slew of overdue revivals beginning in 2009 (including a production at Versailles itself) boded well for Corigliano’s triumphant return to opera.

When The Lord of Cries commission was announced, the B-movie subject matter was admittedly a disappointment. Ever since Anne Rice and Stephenie Meyer ran vampires into the ground, it’s become impossible to take these monsters seriously. Defanged, they seem to persist only in parody and bland entertainment.

It’s precisely the mash-up with Greek theater that has allowed Adamo to resurrect vampiric legends so brilliantly. The ancient rites depicted by Euripides restore the sense of myth and mystery that was sucked from vampire lore ages ago. Dionysus announces in the opera’s prologue that, deprived of the devotion he’s due, he will descend upon late-19th-century England in a new incarnation. The cast of characters he encounters in London are all drawn from Stoker, yet their roles and relationships have been tweaked to mirror the dramatis personae of The Bacchae.

Pentheus, the Theban king, is replaced with Dr. John Seward, head of Carfax Asylum. In the guise of Dracula, Dionysus lays claim to nearby Carfax Abbey and demands that Seward pay tribute to his dark, animalistic ways. Seward stubbornly refuses, blinded by his Victorian mores and ignoring the guidance of his mentor, van Helsing (a combination of Euripides’s Cadmus and Tiresias). As retribution, Dracula and his three sisters whip up the women of London into a frenzy — even seducing the upright Lucy Harker, a married woman after whom Seward pines. The sisters trick Seward into momentarily taking on Dracula’s identity as the Lord of Cries, saying this transformation will allow him to hunt down and destroy his enemy. To his horror, Seward discovers that, in his delirious mania, he has instead beheaded the object of his suppressed desire.

As a composer, Adamo has never been able to replicate the success of his popular Little Women adaptation from 1998. But with four operas under his belt, all to librettos he wrote himself, he has an innate understanding of how to construct a musically oriented text. His regular meters and rhyme schemes are a fresh alternative to the overly prosaic dialogue favored by today’s librettists. And while he accurately replicates the language of 1890s London, his verses never cross over into Gilbert and Sullivan silliness.

Adamo provides Corigliano with a set of recurring mottos that serve as the basis for a corresponding system of leitmotifs. It’s a tried-and-true method of granting an opera musical structure, but one that contemporary composers have forgotten or snubbed. Moreover, the cyclic repetition of certain phrases — such as the three admonitions that Seward obstinately rejects — lends the drama a ritualistic atmosphere.

In response to the libretto’s blend of paganism and Gothic horror, Corigliano has composed a score that radiates eerie, nocturnal energy. “The children of the night — what music they make!” exclaims Bela Lugosi’s Dracula in one of the 1931 film’s most lampooned scenes. But this same line loses all its cheesiness in the opera when the Lord of Cries summons his minions, his calls enveloped in Corigliano’s chilling sonic nightscape. Led by conductor Gil Rose, members of BMOP — often instructed to improvise — conjure the sounds of scurrying, screeching, flitting, and flapping.

Dracula never changes into a bat in this version. Rather, countless instrumental wolf howls — including the primeval blast of a conch shell — indicate his preferred lupine form. But given Corigliano’s knack for the wild and uncanny, it’s surprising that the Act 1 bacchanal never surpasses the level of a mild rumpus. The imitations of Middle Eastern music, meant to evoke some archaic Hellenic mode, feel closer to the hackneyed exoticism of Camille Saint-Saëns’s Samson and Delilah than the sacrificial violence of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

More lyrical passages are redolent of musical theater, especially Stephen Sondheim. In fact, in addition to the shared penny-dreadful setting, there are a handful of numbers that seem strongly indebted to Sweeney Todd: a “London in Chaos” chorus recalling “City on Fire,” a sweet reminiscence song for Lucy that resembles Johanna’s “Green Finch and Linnet Bird,” a tortured mea culpa sequence for Seward with a self-flagellating refrain like Judge Turpin’s in “Johanna.” This isn’t to say Corigliano is a mere copycat — he’s a talented tunesmith in his own right and fashions some thoroughly memorable melodies.

Dracula’s theme, for instance, tends to hypnotize with its slinking phrases and odd 7/8 meter. In the title role, Anthony Roth Costanzo is positively cobra-like, tracing his aria’s deceptively gentle contours with a beguiling and irresistible air. Indeed, the countertenor’s delivery couldn’t be further removed from the deep-throated Draculas of cinema. For much of the opera, he hovers around a vibratoless piano dynamic — hushed, subdued, seductive, yet unnervingly so, as if each word were concealing a threat. When he does strike, there’s venom in his stinging top notes.

Fans of Costanzo’s portrayal of Philip Glass’s Akhnaten will appreciate the same supernatural scale of his performance as the Lord of Cries. His godliness here, though, is tinged with something shadowy and hellish — especially at the apotheotic moment when he reveals his true vampiric nature. Over a blazing E-major chord (intended to clash with Seward’s mock-heroic E-flat), Costanzo unleashes a melismatic line of unearthly intensity. You can practically picture him atop a craggy, windswept rock, bathed in purple light.

Supporting the countertenor are Dracula’s “weird sisters,” played by a close-harmony trio in the vein of the vixenish triplets from The Magic Flute or Das Rheingold. Leah Brzyski, Rachel Blaustein, and Felicia Gavilanes are wickedly mischievous, their voices interweaving in playful counterpoint or blending into an inhuman super-voice. Baritone Jarrett Ott offers a fascinating character study as the unyielding Seward, his tone of sanctimonious pomposity giving way to neurotic self-disgust when he’s left alone with his shame. Even if poor Lucy is ripped apart in the end, soprano Kathryn Henry is still able to endow her with self-liberatory dignity. Goaded by Dracula, she tears off the pearl necklace symbolizing her marriage shackles, rising to a clarion high C of pure ecstasy before being led to the slaughter.

With all this extramarital intrigue, I was struck by the absence of the usual homoeroticism associated with The Bacchae — especially in an opera by a husband-and-husband team. Euripides’s drama has long attracted gay composers like Karol Szymanowski, Harry Partch, and Hans Werner Henze, who play up the undertones of Pentheus’s lust for Dionysus in their operatic adaptations. While Seward briefly remarks on Dracula’s androgynous beauty, his forbidden love for Lucy is squarely heterosexual.

But by the final chorus, it becomes clear that the entire work stands as a larger, more universal allegory for repression — queer or otherwise. Dracula is no villain to be slain but a representation of the overwhelming carnal appetites that devour us when left unsatiated. The Odyssey Opera Chorus, softly yet severely intoning an a cappella medley of the work’s leitmotifs, imparts the terrible lesson of Seward’s downfall: “behold the danger / Of thwarting passion! Naming it sin! / You may assuage the priest without: / But not the beast within.”