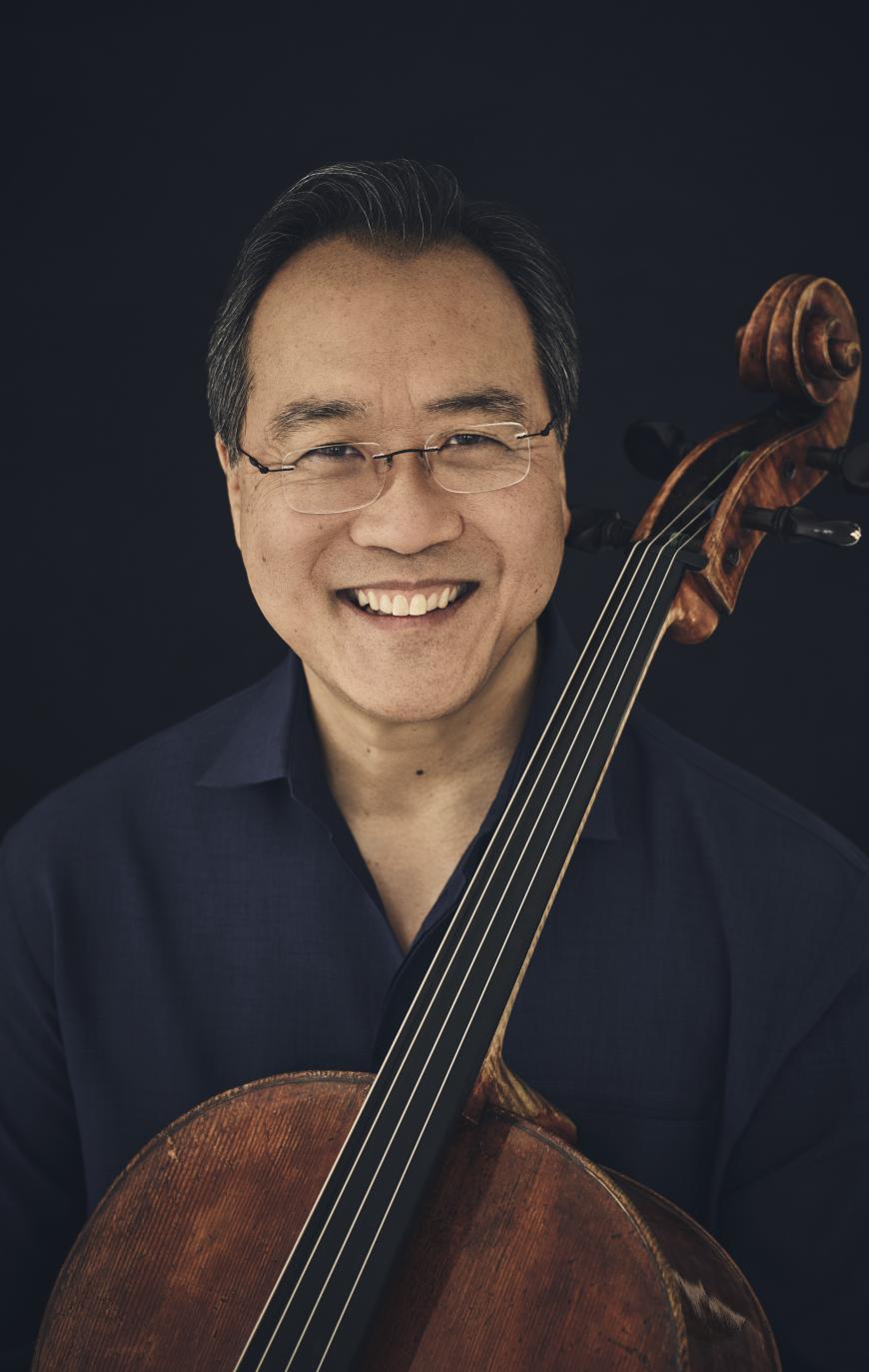

Years ago, an American pianist who had attended Juilliard when Yo-Yo Ma was a young student there said to me, “We all knew he was different, as if there were a halo on his head. He was set apart even then.”

Few musicians have represented traditions of excellence for as long and as dependably as Yo-Yo Ma. With an artist so distinguished, from the Kennedy administration to the present, there is also bound to be dissent, the naysayers and critics who take aim and fire.

On April 2 at Davies Symphony Hall, Ma offered what is likely his final program with pianist Kathryn Stott, a longtime collaborator who retires at the conclusion of 2024. The program, which was designed by Stott and which the duo repeated at Walt Disney Concert Hall the next night, was, in Ma’s own words, “a celebration of the time we have spent together, and in each piece a glimpse of the explorations we have shared.”

Those explorations — works often beyond the classical canon — have been a sore point in some corners for decades. Talk of crossover music, soundtrack music, and the like have clouded the matter of what a supremely talented musician should devote his time to.

Nevertheless, on Tuesday evening, the duo — one of the strongest pairings in recent history — continued their explorations with eight works, four from the 20th century, along with two encores: an exquisite and timely reading of the “Prayer” from Ernest Bloch’s From Jewish Life and Cesar Camargo Mariano’s Cristal.

While our ears were adjusting to Ma’s refined, sometimes faint, multi-timbred sound in Gabriel Fauré’s Berceuse, Op. 16, it seemed the pair took a few bars to find each other rhythmically — or that was the impression of Ma’s soft opening to Stott’s softer ostinato. There is nothing complicated about this jaunty, gently lilting lullaby in 6/8, but its rhythmic structure didn’t seem to project adequately to the ends of the hall.

And there is the crux of the matter: Ma’s mastery is so far past the point of nitpicking that to do so is truly to miss the woods for the trees. As a musician, I have never experienced a more moving, more skilled communicator. And that is why I voice my dissent with the obstinate haters, for the experience of Ma’s music-making still is truly unique, no matter the repertoire.

How many musicians evoke the larger questions of life, about existence or a greater power, while they’re playing, as Ma did in Nadia Boulanger’s “Cantique,” ethereal beyond description, sung heartrendingly on the cello above Stott’s brilliantly weighed rhythmic ostinato? He did it again in Arvo Pärt’s seemingly bare Spiegel im Spiegel, performed with slow alternating depictions of the planet on a projector.

And in Sergio Assad’s “Menino,” with just a wave of the bow and the subtle rhythmic nuances and countless gradations of color that followed, Ma conjured in the listener’s mind cherished memories of loved ones. These things just don’t happen at every recital, but with Ma, they seem to happen every few minutes or so.

The duo completed their first half with a kaleidoscope of emotions in Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata, Op. 40, a work of whimsical beauty. Ma found rare depths in the Largo with his long, multilayered dynamic bowing, offering a vast array of tonal differentiation. Stott, in turn, lightened the mood in the preceding Allegro, sprinting up and down, perfectly coordinated in a passage reminiscent of Sergei Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto.

But the centerpiece of the evening, César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major (arranged by Jules Delsart), was what we came for. Ma’s prodigious technique has been reexamined and retried by every succeeding generation of cello students, and Tuesday revealed that his intonation and powers of communication are as secure and expressive as ever.

Ma delivered some of the opening material with an easy, debonair elegance, while other sections were preserved with authority and a touch of modesty. He made beautiful sounds in the singing of the Recitativo-Fantasia, where an array of vibrato — all coming from different parts of the arm up to his knuckles — evoked changes of mood and transported us to the triumphant conclusion of the Allegretto poco mosso and that wondrous key change to C major, delivered con brio, which encapsulated the celebratory spirit of the evening.

It is a shame Stott and Ma will likely never perform together again in San Francisco. The city could use a reminder of the power of this art form when barriers are broken. And Ma’s recordings simply don’t do his ravishing live sound justice. I am convinced, with every listen, that his forays into the outer limits of the classical repertory (and beyond) continue to refine what is at once his greatest and rarest gift, one recognized long ago by his peers at Juilliard: transcendence.