Jeff Anderson, San Francisco Symphony’s principal tuba, is looking forward to an eventful March, unusually (and happily) up front in the life of a musician with an instrument mostly relegated to the back of the orchestra. The fact is, tuba concertos are few and far between. Well, yes, there is always “Tubby the Tuba,” but ...

Anderson, who regards the instrument in a far different light, will be featured on the cover of the S.F. Symphony programs as “musician of the month,” including at concerts he is headlining as the soloist for the U.S. premiere of Robin Holloway’s Europa & the Bull, a 20-minute work that depicts, as the composer puts it, “Jupiter’s lustful hankering for the beautiful nymph, Europa.”

First mentioned in the 8th-century B.C. Iliad, Europa, the Phoenician woman for whom the continent of Europe was named, became the mother of King Minos of Crete, who, in turn, fathered such great operatic figures as Ariadne and Phaedra. It’s a musical royal lineage. The March 23–24 concerts, titled “MTT Conducts 20th-Century Greats,” also includes Cage’s The Seasons and Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

Europe & the Bull tells the story in seven parts, with the role of the bull/Jupiter portrayed by the tuba soloist. The sections express a dynamic range of action and emotion, from the tuba’s declamatory entry and gentle wooing, to the aggressive abduction and ensuing violence, and a solemn, hymnlike conclusion.

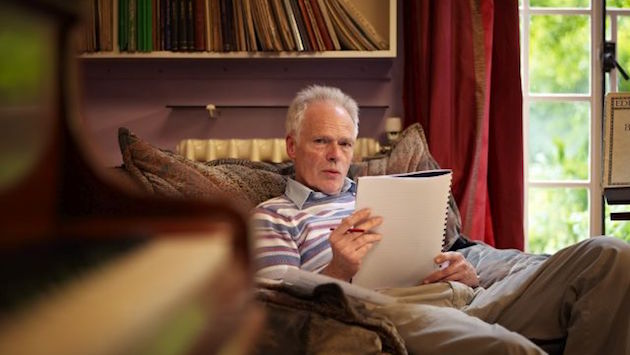

Explaining that he found the story to be “ideal imagery for the tuba,” Holloway drew equal inspiration from the instrument itself: “I was initially inspired by my love of the noble solo instrument that is usually confined to roaring or brooding at the bottom of the brass section, plus admiration for some outstanding players of it when a rare moment of exposure reveals, as well as sheer power, their powers of cantabile and eloquence.”

Holloway’s association with SFS began in 1990 and the U.S. premiere of his Serenade in G. The orchestra has since performed the U.S. premieres of his Third Concerto for Orchestra, in 2000, and his Viola Concerto, in 2002, as well as the world premieres of Clarissa Sequence, in 1998, Fourth Concerto for Orchestra, in 2007, and Peer Gynt, in 2013.

The commission for Europa & the Bull originated with an extended trip to San Francisco, in 2013. In several performances of his works, Holloway was impressed and inspired by Anderson’s playing.

The work was co-commissioned by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society, for its 175th anniversary, and the San Francisco Symphony. At its Liverpool premiere, in 2015 — with Robin Haggart, that orchestra’s principal tuba, as soloist — the work was praised in The Guardian for Holloway’s “exploration of the lyrical, even seductive qualities that give the instrument a certain nobility.”

Anderson sees many positive aspects of his instrument. He is not only the principal tuba player, but also the only one — it’s not like string instruments or even other brass: the tuba is singular:

It affords me a great opportunity to play with all the sections. Composers write in such a fantastic way for the tuba, I can be the foundation of the brass section, which is usually thought of as the tuba’s main purpose, but it’s also such a versatile instrument.

I can blend in with the basses in a Prokofiev symphony, I can be the foundation of that organlike sound in Bruckner, and there are the solo opportunies — in Petrouchka, the opening of the third movement of Mahler’s First Symphony, with string bass and bassoon, and others. The tuba doesn’t sound the same; I vary it from brassy with the brass section, dark with the lower strings, color to fit in with percussion, the woodwinds, and so on. The instrument is capable of clear, foggy, dark, brassy, woody sounds.

Composers guide us in different ways. Berlioz and French music in general is often more clear and accented; Prokofiev wants a more dark and brooding sound, Wagner is yet something else.

The Cage piece, The Seasons, a 1947 collaboration with Merce Cunningham, was originally called “a horror” in the Dance Magazine review and fared only slightly better in Dance News, which found it “a generally pleasant piece, purposely fragmentary but unintentionally, one supposes, aimless.” Susan Feder’s program notes provide a sympathetic explanation:

Structure for [Cage] was principally rhythmic, as opposed to his teacher Schoenberg’s reliance on the structure of pitches. Cage used rhythmic patterns as an organizing principle; the resulting music had a certain static quality, lacking traditional climaxes. ...

Fully notated, the score presents a world close to nature: Sounds are shimmering, gurgling, twittering, occasionally threatening, but mostly gentle. Movement is slow and relaxed, the passage of time barely perceptible.