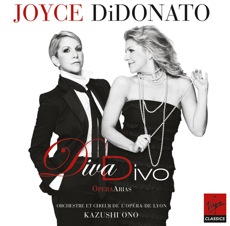

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato’s 2010 disc, Rossini: Colbran the Muse, sure is a tough act to follow. Not only did it net the Kansas-born artist Gramophone Magazine’s 2010 Recital of the Year award, but it also helped crown her that magazine’s Artist of the Year. Which is all the more reason to stand up and holler about her latest recording, DivaDivo (Virgin Classics), which displays an artist so on top of her form that it has a good chance of snaring another round of awards.

First and foremost, there is the astounding versatility of the voice. For a mezzo distinguished in part by the dark fullness of her lower range, DiDonato begins the recital on an ecstatic high note, sounding like a soprano in Massenet’s high-lying aria, “Je suis gris!” from Chérubin. Catch her glorious high As and soaring spirit on the clip that accompanies this review. If ever there were a recital opener designed to make you sit up and take notice ...

Listen To The Music

Massenet: “Je suis gris!”Rossini: “Nacqui all’affanno”

From there, it’s one high after another. Some may miss the sense of innocence a singer like Kathleen Battle brought to Susanna’s “Deh vieni, non tardar” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro. Nonetheless, DiDonato’s very individual response to the opening recitative, “Giunse alfin il momento ...” sets her interpretation apart from all others (in a good way). And if it's high-spirited virtuosity that rocks your boat, try her breathtaking rendition of Rossini’s sparkling “Nacqui all’affanno,” his crown jewel at the end of La Cenerentola. DiDonato is one mezzo who doesn’t wait for the recap before she starts throwing in one dazzling variation after another. Only Cecilia Bartoli among today’s current bumper crop of mezzos can sing as brilliantly and as fast, and with such high spirits. The performance is sensational.

Equally remarkable is the album concept. Not only does it showcase DiDonato in both skirt and pants roles — seven “trouser roles” are represented — but it also counter-poses different composers’ takes on the same character. With both male/female and composer dichotomies playing against each other, DiDonato unifies the concept with the sheer brilliance of her artistry.

Here’s just a taste of what she offers. From different centuries, we’ve got Mozart’s Cherubino and Massenet’s Chérubin. Even more delicious, the juxtaposition of Massenet’s Prince Charming from Cendrillon with Rossini’s Cinderella from you know what. Gluck’s La clemenza di Tito gives us the trouser role of Sesto, while Mozart’s opera of the same name provides the skirt role of Vitellia. Characters from Gounod, Berlioz, Bellini, and Strauss present further contrasts.

The final impassioned selection, sung by the Composer in Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos, may form a nice bookend with Chérubin’s soaring opener, but it’s from such a different milieu than everything else that I find it a little unsettling. Nonetheless, it again underscores the mezzo’s versatility. Some may prefer a sound more virginal, innocent, or fragile for some of these characters, but no one in their right mind will scoff at the quivering sentiment and sheer beauty of tone with which DiDonato infuses these portrayals. A tour de force and then some.