Whenever authoritarian forces seem to be gaining ground upon democracies — as is happening now around the world — inevitably the iconic example of Germany’s Weimar Republic turns up in the zeitgeist as Exhibit A. That said, it’s a pretty good time right now for the Los Angeles Philharmonic to be holding its Weimar Republic Festival. There was supposed to be a Weimar program at the LA Phil last April, but it was postponed — and in any case, this one looks to be far more encompassing in the LA Phil’s by-now-habitual multidisciplined, multimedia way.

As in the abandoned 2019 program, Esa-Pekka Salonen was in charge — and you knew that sparks were going to fly, for everything he programs these days as conductor laureate turns out to be an event. The LA Phil ups its game even beyond its usual high level; the programs are cannily constructed, studded with things that you only tend to hear on recordings.

None were more unusual than — nor as much fun as — the opening work on the opening program (heard Saturday night, Feb. 8), Paul Hindemith’s brief Rag Time (on a theme of J.S. Bach). It’s not really ragtime at all, not in the American sense. This was the wild young Hindemith, 26, sending up the C-Minor Fugue from Book I of Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, pushing the tune around in a loud, chaotic, brassy, funny romp with a Mahler-sized orchestra (indeed one of the permutations of the tune sounds like a lick from a Mahler symphony). Salonen’s revved-up performance blew all of the recorded versions I’ve heard out of the water.

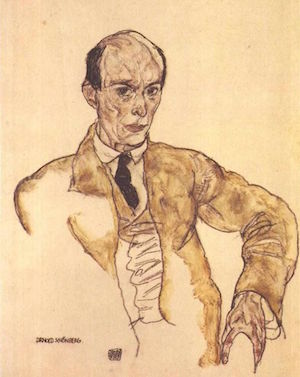

In dealing with the Arnold Schoenberg of the 1920s, rather than venturing into 12-tone territory, Salonen linked Schoenberg’s treatment of Bach with that of Hindemith by playing two chorales, “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele” and “Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist” that Schoenberg gussied up for a huge orchestra. This was a much more serious homage; Schoenberg wanted to hear more varied colors in these chorales than a pipe organ could provide, and Disney Hall was just the place to capture and spotlight as much of the tapestry of kaleidoscopic detail as could be heard.

Hindemith’s 1934 masterpiece, the Symphony: Mathis der Maler, falls slightly outside the Weimar Republic’s timespan (1918–1933), but never mind; it was shrewd programming to illustrate how his style had mellowed somewhat from his flaming youth. Back in 1999, Salonen made a recording of it with the LA Phil that for some reason (the alleged toxicity of the name Hindemith to the American CD-buying public?) was not released in the U.S., not even in Los Angeles. Fortunately, it now exists on the stream for all to hear — and Salonen took the piece just a mite faster than he did 20 years ago. Yet Salonen’s way still unfolded at a slower, more luxuriant pace than most, beautifully illuminating that lusciously serene chord that opens the symphony, having the golden brasses sing out, and building the percussion crashes in the third movement with shattering impact. A really distinguished performance.

Early birds got a look and listen at a Kandinsky-inspired installation in BP Hall by Nicole Miller called Transition, which featured swirling, flashy laser art on the wall and narratives and songs in a soul/gospel idiom from singer Kyshona Armstrong and violinist Lady Jess (Jessica McJunkins). Although the sounds were supposed to electronically trigger the sights, the laser art had nothing to do with what Armstrong was saying or singing — and the thing grew wearisome over the span of half an hour