Photos by Cory Weaver

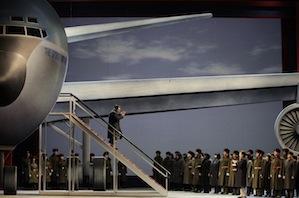

For political junkies in an election year, the arrival of Air Force One might mean a chance to see Barack Obama give a speech. For opera fans, the arrival of Air Force One means that John Adams and Alice Goodman's brash and exhilarating Nixon in China has at last reached the stage of the San Francisco Opera, 25 years after a reading at Herbst Theatre and the opera's premiere at Houston Grand Opera. Strongly cast, beautifully played, and presented in a handsome and effective production from Vancouver Opera, the opening performance affirmed Nixon's standing as a musical and theatrical masterpiece and one of the great operas of the 20th century.

Goodman's libretto is not a narrative of the events of Nixon's 1972 trip so much as it is a fantastical, poetic, and often quite funny meditation on what the participants might have been thinking or feeling during particular incidents, from the commonplace to the paranoid to the oracular to the nostalgic. It's an opera of character, intensely dramatic despite an episodic structure and a plot that has almost no direct conflicts among the characters. The political situation and philosophical clash of Communism and capitalism provide their own background drama, of course, but we see this more in verbal jousting than in outright conflict. And you can have only the deepest respect for a libretto that succeeds in presenting the disgraced and widely despised Richard M. Nixon in a sympathetic light, as a complex human with his own fears and loves.

Adams sets this untraditional libretto to a score of kaleidoscopic brilliance, layering complex cross-rhythms and syncopations atop one another and orchestrating each number with the hand of a master colorist. In how many operas do you find two pianos and four saxophones in the pit? And how many operas make you want to get up and dance, repeatedly? Not many, but the sheer rhythmic vitality and drive of Nixon can make it mighty hard to just sit still and listen.

But listen you must, because Nixon is as musically compelling as anything to reach the operatic stage in the last century.

But listen you must, because Nixon is as musically compelling as anything to reach the operatic stage in the last century. However quirky the libretto might be, Adams handily employs traditional operatic forms, in ensembles and in Pat Nixon's lyrical Act 2 soliloquy or Chiang Ch'ing's coloratura mad scene/rage aria, “I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung.” Elsewhere, he writes with a more conversational tone, in the many asides and conversational stretches.

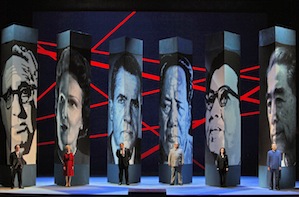

Erhard Rom's attractive production uses a combination of strong geometric designs, colors, and projections, designed by Sean Nieuwenhuis, to delineate the space on stage and set the scene. Photos of Mao and projections of the American and Chinese flags dominate some scenes. Red is used prominently, reminding the audience that red has strong traditional associations in China, and also that the country was so often referred to as “Red China” in the 1970s.

Charmingly, the prompter's box is painted red rather than blending into the set, and is used as a prop from which several characters stand and sing. Pat Nixon is dressed in red for about half the opera; she really did wear that red coat on the China trip. The costumes, by Parvin Mirhady, are all true to the 1970s and closely reflect what can be seen in photos of the trip. Michael Cavanagh's lively direction works well for both the character interactions and the details of the staging.

Nixon in China has a technically difficult score, between the idiosyncratic scoring, the layers of syncopation, and the harmonic language; it's a challenge for any orchestra that doesn't play Adams on an everyday basis. Nonetheless, the opera orchestra sounded strong and gorgeous, under the firm and experienced leadership of Lawrence Renes, who led the UK premiere of Adams' Doctor Atomic several years ago. The large orchestra includes some players not credited in the program, on instruments that give the orchestration much of its unusual color. They all played like champs, so let's name them here: Matthew Piatt on keyboard sampler; David Hanlon and Robert Mollicone on piano; and Dale Wolford, David Henderson, James Dukey, and Kevin Stewart on various saxophones.

Baritone Brian Mulligan has appeared in San Francisco several times in the last few years, but never before in so prominent a role as Richard Nixon. He sang with lyrical beauty and at times looked and moved spookily like the late President. Lyric soprano Maria Kanyova, who has sung Pat Nixon a number of times, looked fabulous and was technically solid, but fell short in warmth and tenderness, sounding too detached to catch the First Lady's naivite and charm.

Hye Jung Lee was a terrifyingly fierce presence as Madame Mao, reaching the stratospheric heights of the role and singing the coloratura with ease. Tenor Simon O'Neill sang Mao Tse-tung with power and brilliant tone while also strongly projecting the character's physical decline. Patrick Carfizzi's Henry Kissinger was well sung and suitably creepy (Kissinger is the only character to be treated like a cartoon rather than a human), and Chen-Ye Yuan was a strong and sympathetic Chou En-Lai. All of the singers were comfortable with the musical style and all embodied their characters' known physical quirks. Ginger Costa-Jackson, Buffy Baggott, and Nicole Birkland made a fine trio of secretaries to Mao, though I wish they'd been given more prominence in the amplification mix. The opera chorus sang sharply and splendidly.

Despite the overall strengths and many virtues of the cast, or perhaps because of them, no individual singer knocked me out. I rather think that it's the sheer power of the opera itself that had this effect. The singers are called upon to impersonate historical personages whose physical and personality quirks are well documented, and they all succeeded in this. While Nixon has been successful as new operas go, in its 25 years history it has received 36 productions, far fewer than La Traviata or La Bohème receive in any single year. Nixon doesn't yet have an established tradition within which singers can begin to differentiate themselves.

No production is perfect, but there's little to fault in this Nixon. Brian Mulligan was intermittently covered during Nixon's entrance aria; later in the opera, there were no issues with hearing him. Perhaps the balances between the orchestra and singers — all amplified, per John Adams' aesthetic preferences — had been adjusted during intermission. You have to wonder whether Lee and Kanyova would have sounded warmer without the close miking. And while the Red Detachment of Women ballet is beautifully danced by principals Chiharu Shibata and Bryan Ketron, one of the three accompanying corps dancers was, distractingly, consistently behind the other two.

No matter. Even though it took 25 years and having the original Houston co-commissioner David Gockley now as SFO's general director, Nixon has finally, splendidly, arrived. Get your tickets now.