One day in the late 1970s, the celebrated American composer Lou Harrison phoned Eva Soltes. “Hello, dear,” the deep, jolly voice boomed. “Glub glub glub, I’m drowning in papers. Can you save me?” Harrison’s growing fame as a pioneering figure in American music, coupled with a car accident that reminded him of his mortality, spurred him to start getting his papers (music, files, correspondence) in order, and Soltes, who was producing 100 concerts a year at Berkeley’s chamber music organization called 1750 Arch Street, seemed to him to offer a solution.

They’d met earlier when Soltes was studying classical Indian dance with the famed teacher and dancer Balasaraswati at Berkeley’s Center for World Music. One day after leaving the class, she walked across the street and saw two bearded men making musical instruments, and occasionally playing them. The center had given the great composer Lou Harrison (1917–2003) and his life partner, Bill Colvig, the workshop space as part of Harrison’s teaching assignment there. Soltes, then a student in her late 20s, often stood in the doorway, just to watch and listen.

Related Article

Lou Harrison Composer Biography

They grew closer when she produced a concert celebrating the centennial of the pioneering American composer Charles Ives, whom Harrison had known. He’d edited much of Ives’ work and had conducted the 1943 premiere of Ives’ Third Symphony, which won Ives the Pulitzer Prize in music.

Soltes recognized the respect that the brilliant, charismatic polymath Harrison commanded. “When you were in Lou’s presence, you’d stand straighter or sit taller or listen a little better,” she remembers. Despite detesting paperwork and already having a full-time job, she agreed to help. Eventually she found Harrison an assistant, but Soltes stayed in his orbit for the rest of his life, producing concerts around the country for him, bringing some order to the chaos of his expanding career, and contributing significantly to Harrison’s emerging recognition as the grand old maverick of American music.

In 1984, Harrison invited Soltes to an event honoring his old mentor, composer and critic Virgil Thomson, who was visiting San Francisco. She brought a video camera that she’d been given by a foundation to document the life of her dance teacher, who had died a week before they were to begin. And Harrison was a year older than Balasaraswati. If her life deserved preserving on film, Soltes reasoned, then surely so did that of an American homegrown, creative genius like Harrison, whose prodigious career stretched from his early percussion ensemble concerts with John Cage in the 1930s through music inspired by Ives and his teachers Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg, and included ballet scores for such choreographers as Jean Erdman and Mark Morris; tuning experiments sparked by his friend Harry Partch; symphonies, concertos, and solo works; and finally the multicultural fusions with the music of Asia, particularly Javanese gamelan music, that culminated his enduring legacy. That day, she shot footage of Harrison and Colvig walking arm in arm in a church — her first video of the legendary Aptos-based composer. But far from the last.

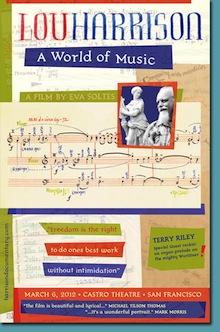

On March 6, the Castro Theater will screen the debut of Soltes’ film, almost 30 years in the making, Lou Harrison: A World of Music. Composer Terry Riley, a friend of Harrison’s, will perform on the theater’s historic Wurlitzer organ, and the event will feature other live music by additional Harrison friends and colleagues, including guitarist David Tanenbaum.

Soltes contributed significantly to Harrison’s emerging recognition as the grand old maverick of American music.

Soltes toted her camera to hundreds of events Harrison participated in, from concerts to lectures to residencies to hikes in the woods to the building of the beautiful straw bale house that he designed for himself in Joshua Tree, California, completed not long before his death, and that now hosts an artist residency program that Soltes administers and that the film premiere event benefits. But she didn’t initially regard her frequent documentation as part of a film biography. Then Harrison spent a year in New Zealand on a Fulbright grant. “I realized how much I missed him and his music,” she recalls, and she realized that his amazing generation of maverick West Coast artists would be disappearing soon. “I understood the impact his music had on people, like it had on me. He was a really great composer who touched people in a deep way. Little by little I came to the idea that we were the first generation that had the ability to preserve the music and words of our treasured artists on video. We’re in the same clan, and he’s my elder. If I didn’t do it, no one else was going to do it.”

With no background in filmmaking, Soltes assumed that she would eventually hire professionals to make the actual documentary, but a film editor who saw her work urged her to make it herself. “Your work has the life in it,” he told her. “Filmmaking is like dance,” she says. “It’s music and movement and content.” She wound up teaching herself much of what she needed to learn, at first by producing radio documentaries for the BBC (about West Coast composers) and for National Public Radio. She made a short film about another composer she worked with, Conlon Nancarrow, that he could take with him on tour, and a longer one about Indian dance. She also enlisted experienced film editor Robbie Robb, who coedited the film with her. Harrison allowed Soltes to use his voluminous address book to contact his friends for support, and she also obtained grants from the Hewlett Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, along with investing her own time and money into the long-gestating project.

“He was a really great composer who touched people in a deep way.” – Eva Soltes

The bigger obstacle turned out to be the sheer wealth of material she gathered. Harrison lived a long, rich, full, active life — and Soltes was there to film much of it. “It was like trying to eat a whale all by myself,” she says. How to cut it down to manageable length? She solved that problem by deciding to make not one but 10 films from the material, including one about his relationship with Colvig, another about the long, troubled creation of his opera Young Caesar, and more. This film focuses on the development of his music. Sometimes working up to 20 hours per day, Soltes completed the last marathon round of major editing after moving her editing equipment to Harrison’s desert straw bale house in 2010, which provided the isolation, focus, and inspiration she needed — including portraits of Harrison and Colvig gazing down at her from the walls).

Using photos, interviews, and of course Harrison's ever-alluring music, the film chronicles his years growing up in Portland, Oregon and around the Bay Area, his early percussion and dance works in San Francisco, his turbulent decade in 1940s New York, and his initially impoverished but ultimately triumphant decades in Aptos, when Harrison became one of the trailblazers in connecting the classical music of East and West. Soltes’ favorite moments include moving shots documenting his 33-year partnership with Colvig, who died in 2000. “I was happy that I was close enough to them to be a fly on the wall,” she says. Harrison long refused to allow her to film him actually composing — “those things are private,” he told her — but finally relented, yielding another precious sequence.

Harrison earned a multitude of of fans during his decades in the Bay Area, but even those who don’t know either his fascinating life or his alluring music will find much to enjoy the film, Soltes says. “He was not only a great composer but also a personality who’s fun to watch. He was always a performer, onstage from the time he was two years old,” she explains. “He was a visionary, a hugely important musical figure, and his life is very inspiring" — especially in the way he persevered in finding his own path despite being so far ahead of his time. Like MTT [San Francisco Symphony Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas, who’s cosponsoring the premiere event with Mark Morris] said, he not only always marched to his own drum — he even made his own drum.”