“It’s almost like chamber music with a groove.”

That’s how Jane Lenoir, an Oberlin-trained flautist, describes the Brazil-based repertoire of the Berkeley Choro Ensemble, which will sweetly welcome the New Year with concerts this month and next around the Bay.

Choro, pronounced “SHORE-oo,” developed in Rio de Janeiro in the late 19th century, where “it was a fusion of European styles,” says Lenoir. “These included waltzes, polkas, dances, and classical music, from European immigrants, but the rhythm itself came from Afro-Brazilians. On the sugar plantations, they had orchestras made up of slaves, and they imported French musicians to teach the slaves how to play opera, masses, and other things. Later, a core of musicians, whose ancestors may have been slaves, assembled in Rio.”

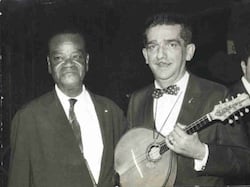

This was an instrumental music, at first delivered by an ensemble of flute, guitar, and cavaquinho, a four-stringed cousin of the ukelele. After the earliest recordings by Pixinguinha, an Afro-Brazilian “child prodigy on the flute who incorporated his classical training,” the clarinet joined choro groups. In more recent years, the bandolim (mandolin) has also had a significant voice in the music, with many virtuosos following the lead of the legendary Jacob do Bandolim.

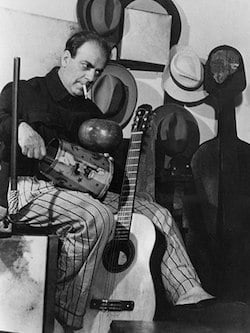

Aside from Lenoir, the Berkeley Choro Ensemble includes Harvey Wainapel on clarinet, Rio native Ricardo Peixoto on seven-string guitar, and Brian Rice on pandeiro (a large Brazilian tambourine). “Harvey is coming from a jazz background,” Lenoir points out, “but choro is a style of music that can accommodate many different approaches.” Classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos created his own choros, as did pianist and composer Ernesto Nazareth.

“The style is classical in form,” says Lenoir. “An ‘A’ section is repeated, then a ‘B’ section, then the ‘A’ section is repeated again, then a ‘C’ section is repeated twice, similar to Bach, Haydn, and Mozart. But there’s also a lot of ornamentation, and improvisation, somewhat like Early Music. And the name of choro comes from the Portuguese verb ‘chorar,’ to cry. In a sense, it’s a lament, a blues. From the start, it gave Brazilian slaves a music they could express themselves through.”

A sizeable population of expatriate Brazilians in the San Francisco Bay Area has helped engender local interest in a variety of forms of their music at restaurants, clubs, and festivals, including samba, bossa nova, and, for a brief period, the sensual lambada. The summertime California Brazil Camp in Sonoma County, this year celebrating its 20th anniversary, has included on its faculty performers and composers from the home country. In addition, several Bay Area-based virtuosos, including Wainapel and mandolinist Mike Marshall, have regularly visited Brazil and brought back choro and other music shared in concerts, recordings, and workshops and private lessons. In 2013, Lenoir and her colleague Rice staged the first of three Festivals of Choro to date, showcasing both domestic and Brazilian performers, among them world-class Israeli-born clarinetist and saxophonist Anat Cohen. Other jazz celebrities, including guitarist Harold Alden, have found themselves drawn to choro and to collaboration with the Berkeley Choro Ensemble.

Lenoir, who still gigs classically at Grass Valley's Music in the Mountains festival and elsewhere, is thrilled with choro’s bourgeoning popularity. Her ensemble has received two grants from the San Francisco Friends of Chamber Music, the first helping to fund their second festival, including the commission of Wainapel’s arrangement of a choro for octet. The current SFFCM grant will support the Ensemble’s first recording, in March of this year, with the commission of a new choro by Peixoto.

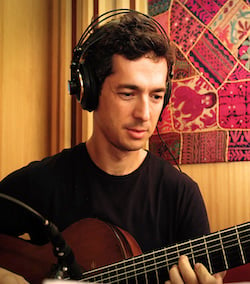

The Ensemble’s current concert series, including on January 15 at Old First Church in San Francisco, and on January 19 and 20 in Davis and Berkeley, with visiting Brazilian guitarist Nando Duarte, will include material from the upcoming album, as well as older standards. In May, the Ensemble will perform with the ECHO Chamber Orchestra.

Lenoir recently returned from recording in Sao Paulo with Alessandro Penezzi, who’s led classes in choro harmony at the California Brazil Camp. She reports the state of choro as healthy in its homeland, and she hopes the Berkeley Choro Ensemble will be able to promote visits from Brazilians over the next few years. “We’re all really good players,” she says, “but we’re still Americans, and we have so much to learn from them.”