A refugee is trapped in an airport, unable to enter the country. That scene played out in airports around the United States two weeks ago, and it played out on the stage of Yerba Buena Center for the Arts this weekend. As eerily topical as it is, Jonathan Dove’s opera Flight was written for Glyndebourne in 1998. It has proven popular, with at least 20 productions across Europe, the United States, and Australia since its premiere. Opera Parallèle presented this sparkling score February 10–12 in a polished production with an all-star cast.

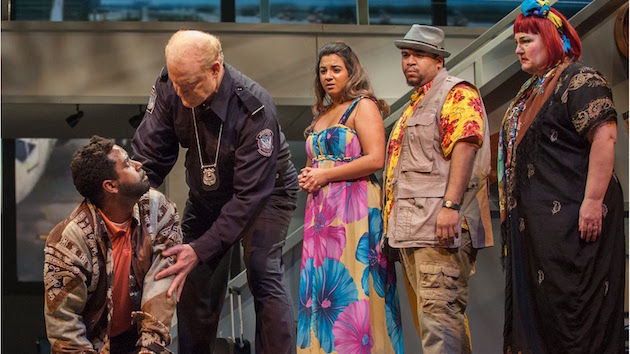

The refugee’s predicament is serious and real. It is based on the story of Iranian refugee Mehran Karimi Nasseri, who lived at Charles de Gaulle for 18 years. (His story also inspired Steven Spielberg’s film The Terminal.) Still, the opera is a comedy, a modern-day Figaro or Barber of Seville. The ensemble cast’s ten singers play the refugee, the airport controller, the immigration officer, and seven airport visitors. A young couple (Bill and Tina) are traveling to rekindle their relationship; a pregnant woman and her husband are headed to Minsk for a diplomatic assignment; a steward and stewardess delight in quick, frantic sex whenever they cross paths; and an older woman waits for her 22-year-old fiancé. When a storm delays their flights, they end up stuck at the airport with the refugee.

Jonathan Dove’s musical idiom in Flight is halfway between John Adams and British choral music. Minimal, modern, vocal lines and orchestral patterns alternate with lush, melodious ensembles. Dove builds the atmosphere into his music: The celesta contributes irritating announcement chimes, and the storm crackles and crashes outside the airport’s windows. There’s even a hint of Sondheim in the opera’s devilishly tricky rhythms and rapid-fire lyrics.

Conductor Nicole Paiement drew a large and nuanced sound from the orchestra. The music covers a wide dynamic range, and it felt immediate and exciting at both extremes of volume. The instrumentalists navigated Dove’s varied style well, precisely tapping out sparse patterns between flights of aching lyricism.

Opera Parallèle has assembled a cast that any larger house would envy, including seven Merola Opera Program alumni. The steward (baritone Hadleigh Adams) and the stewardess (soprano Maya Yahav Gour) showed off clear voices and unabashed commitment to their roles’ physical demands. Adams followed what seems to be a local operatic tradition of also showing off his toned abs. Renée Rapier sang the Minskwoman with a ringing mezzo-soprano, most stunning on her single, long “No!” as she refused to board the plane with her husband (sung by Eugene Brancoveanu in a cavernous baritone).

Amina Edris proved an ideal vocal fit for Tina, producing a big sound with lots of ping and smooth phrasing. Her enraged coloratura in the opera’s second half was particularly funny and technically impressive. Chaz’men Williams-Ali played her unhappily married husband Bill, singing with a strong tenor and delighting the audience with his awkwardness when Bill was discovered pantsless after the storm.

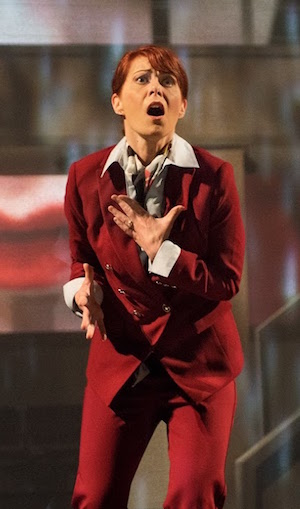

Soprano Nikki Einfeld confidently sang the controller’s stratospheric notes and difficult intervals with piercing intensity. The full-voiced bass-baritone Philip Skinner was luxury casting for the small role of the immigration officer. As the older woman, Catherine Cook displayed a booming mezzo and a flair for comedy — in both her facial expressions and her accessories.

The opera’s most beautiful vocal writing is reserved for the refugee, sung by countertenor Tai Oney. The textures in his voice ranged from a haunting, incisive straight tone to a rolling vibrato. Oney’s gorgeous sound and careful control have already earned him a high-flying career, and I expect to see him at top houses for years to come.

The set (by Dave Dunning) was a perfect, slightly tongue-in-cheek rendering of an airport. Uncomfortable-looking banks of black and chrome seats dotted the lower level, with the “OP Airlines” check-in desk dominating the scene. Suitcases embedded in the wall around a flight status monitor evoked typically bad airport art. Stairs up to the control tower and boarding area allowed the blocking to play with elevations. Supernumeraries purposefully strode across the set to board their flights at the appropriate moments.

The production’s rare misses were in the staging. As the Minskwoman delivers her child (in what must be the world’s shortest labor), the tension in the score builds. But for most of this exciting section of music, she was offstage. A birth should be a wonderful opportunity for a coup de théâtre, but director Brian Staufenbiel missed the chance.

The projections also failed to live up to their potential. The images were individually good: planes arrived and departed, the storm raged, and the Minskman looked worriedly out the plane window for his wife. But they were tiled badly. Too many videos played at once, and some partially covered others. The result was distracting.

In the end, everyone in Flight helps the refugee just enough to feel like they’ve fulfilled their obligations and get on with their lives. They ensure he doesn’t get deported, but he remains stuck in limbo, living in the airport under the controller’s cold gaze. In Opera Parallèle’s staging, he ignored the controller’s pleas to look at her and instead focused on his lucky stone. The ambiguity saved the opera from a saccharine ending. It also serves as a reminder: The refugee’s dilemma isn’t resolved. There is more that we can and should do.