I’ve never shot fish in a barrel (has anyone?), but this list could be as close as I get. Librettos and librettists are regularly raked over the coals, and there are plenty of classical music aficionados who find opera, with a few important exceptions, embarrassing. Even a true Italian opera-lover like me, able to swallow the improbabilities of La sonnambula without batting an eye, may flinch as the huge wet-blanket ending of Don Carlos approaches: The not-really-dead Emperor Charles V conducts his wayward grandson into a monastery cloister. To do what? — watch old episodes of Glee on TiVo?

Still, we all know that Don Carlos doesn’t have a bad libretto, just a good one with some major flaws. The same is true of many great operas. A larger problem is generic: Many folks (Italian opera-lovers aside) have problems with romantic melodrama, that staple form of Italian opera.

The scorn constantly heaped on Il trovatore and its brethren is mistaken, though. Melodrama thrives on outsized emotions and multiple plot reversals. As in an action film, not providing enough interest is a much bigger sin than stepping over the line of believability. So Trovatore has risible moments, but also hair-raising ones. The character of Azucena is one of Verdi’s most original characterizations, and anytime you have Dolora Zajick or another commanding artist in that role, it’s a great show. Maybe not great art, but fantastic entertainment, which is what Italian opera-lovers really want (when they’re not busy judging singers).

Melodrama thrives on outsized emotions and multiple plot reversals.

This list of phenomenally bad librettos can’t hope to be exhaustive, but by getting into the truly bad, we gain perspective on librettos in general, separating true dreck from the merely flawed. All the librettos on this list share one thing in common: They totally sink the operas they’re associated with, even though, in most cases, there’s good music in the show.

There’s a broad swath of bad writing represented here, rather than a focus on the limitations of a single genre. I also avoided loading the list up with contemporary operas, since I know most of them only by report and the really bad ones leave few traces. The top few on the list, of course, are so ludicrously execrable that they constitute their own form of dementia (or, in one case, coercion).

If you can stand to look, here’s the Top Ten ugliest wreckage on the operatic highway (only the first five bad librettos, with the final five to be described next week):

10. Edgar

(Femme Fatale Division) Want to know why Puccini was so careful about selecting librettos and librettists in his career? Because he had worked on Edgar with Ferdinando Fontana. Edgar (1889) was Puccini’s second opera, and it has enough good music in it that the composer tried to save it, editing and reworking it several times and using some of the music he cut to fashion the great Act 3 duet in Tosca.

Edgar has a totally original plot, in which a wayward young man is caught between the love of a pure young woman and a free-spirited, sensual, Gypsy woman … what, you know that story?

The stereotyped characters have to be aggressively over-the-top to assert their individuality. As libidinous, amoral man-eaters go, Tigrana may not be the bottom of the barrel, but she works so hard to get there that her defiant sallies seem pushed on her by the heavy hand of the librettist:

Sia per voi l’orazion, È per me la canzon! Vo’ cantar, vo’ trillar! Chi non vuole ascoltar Torni in chiesa a pregar! (You can have your prayer, I’ll take a song! I’ll sing it, I’ll trill it! And whoever doesn’t want to listen can go pray in the church! — Act I, scene 6)

The bizarre plot turns similarly come from beyond the characters’ motivations. Instead of simply running off with Tigrana, Edgar wounds his best friend in a knife fight and burns down his father’s house, because you should know that Tigrana is a bad influence on him.

The craziness comes to a tipping point, as it must, in the last act, in which Edgar pretends to be dead, so that he can, in the guise of a monk, test Tigrana’s fidelity. Predictably, she fails, while Fidelia, true to her name, comes through like a champ. Unfortunately, Tigrana stabs her to death in the next scene. Oh, the irony!

Believe it or not, this was not the last libidinous, amoral, man-eater, Gypsy character that was pushed on Puccini. Maybe because of the scars left by Edgar, when the subject of the psychotic Conchita came up, Puccini refused it. Riccardo Zandonai set it, and it was a big hit.

9. Fierrabras

(Un-Moored Division): Of all the great composers who never produced a great opera, Franz Schubert has to be the most surprising. One of music’s greatest melodists, supremely adept at creating atmosphere and conveying character and emotion in song, Schubert is the natural who went astray thanks to incompetent librettos. Neither of his grand operas, Alfonso und Estrella and Fierrabras, has been able to break into the repertory, despite some inspired music. The latter (completed in 1823) can’t even manage as many performances as Bizet’s incoherent, unbelievable Indian fantasia, The Pearl Fishers. Now, that’s a bad libretto.

Alfonso has taken a lot of bashing because its librettist, Franz von Schober, was a rank amateur whose product suffers from a lot of beginner’s mistakes in pacing, dramatic exposition, and plain crappy lyric-writing. But I cast my vote in the Bad Schubert Libretto contest for Fierrabras, libretto by the equally inexperienced Josef Kupelwieser, which, in addition to those faults, is way more than three hours long and has a tendentious plot that would make even an opera seria fan despair. Many great operas have been based on the geste of Roland, Charlemagne, and the Franks’ conflict with the Moors of Spain. This is not one of them.

You might think that the title The Bloody Nun would put your average operagoer off his feed.

It’s far from easy to keep things straight in this opera: It has fourteen characters, two of whom are named Roland and Boland. There are two tenor heroes, one of whom disappears for the entire second act and plays a supporting role in the third. Unfortunately, the disappearing tenor is also the title character (whose name, incidentally, the librettist couldn’t even spell correctly — it’s Fierabras in the 1811 romance from which the opera comes). He does get one of the two proper arias in the opera but, despite converting to Christianity, doesn’t win his girl.

Fierrabras was written at the request of the management of the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna, but when they saw the piece, which they had already advertised, it was put aside and not performed until 1897.

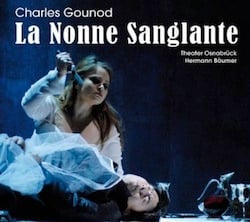

8. La Nonne sanglante

(Gothic Horror Division) You might think that the title The Bloody Nun would put your average operagoer off his feed. Hardly. The libretto rights to La Nonne sanglante were held, for a while, by Hector Berlioz, who composed a bit of it before giving up. Verdi passed on it, and so it fell to the up-and-coming Charles Gounod. The first production, by the Paris Opéra in 1854, had the happy result of getting the general manager fired.

The libretto for The Bloody Nun was written by Eugène Scribe, one of the foremost professionals of his day, so its problems are not caused by amateur mistakes. The plot is a little bizarre, not to say gruesome, but then it’s taken from one of the most popular horror tales of the 19th century, Matthew Lewis’ story The Monk. Rodolphe, the tenor, plans to elope with his beloved Agnes, who will be disguised as the ghost of the bloody nun who supposedly haunts the castle. However, the ghost herself appears and he runs off with her by mistake. To get rid of her, Rodolphe must take revenge on her murderer, who turns out to be his father.

The real culprit here, though, is the whole genre of French grand opera, whose conventions demanded a historico-political superstructure, a ballet, couplets for the page boy, lots of chorus participation, and a five-act layout, all of which fatally delay what should be a taut thriller. And at the end, when the father is making his fatal decision and then rushing into the chapel to be murdered (and thus expiate his sin) — a moment when the horror should be overwhelming — Rodolphe and Agnes conduct an argument about her right to know all the plot details. You want Stephen King but you get half-baked Racine. The Bloody Nun should never have been cast in the mold of classic tragedy.

By the way, one of the first, and most durable, hits of French grand opera was Robert le Diable, which features a ballet of the ghosts of debauched nuns. So one measly bloody nun was hardly likely to cause offense, right? (Wrong: The new manager took the piece off, in the name of decency.)

7. The Maid of Orleans

(Cecil B. DeMille Pageant Division) Fresh off his brilliant Evgeny Onegin, Tchaikovsky decided to do something really populist that would make his name a household word. He decided to take on Schiller’s famous play The Maid of Orleans, which had already been butchered several times on the operatic stage (see, for example, Verdi’s not-so-wonderful Giovanna d’Arco). Premiered in 1881, the opera was, in fact, hugely successful with its first Russian audience. But two weeks later Tsar Alexander II was assassinated and the opera season was shut down.

Just as with all other operatic adaptations of this material, Orleanskaya deva is a colossal mistake. In this version, Joan of Arc is furnished with a lover from the enemy camp, the Burgundian soldier Lionel. Because, apparently, a chorus of God’s angels singing in her ear is not enough motivation for her. Also, those are the rules of French grand opera, on which model Tchaikovsky’s opera is founded.

But there is a dance of page boys and dwarves and clowns: There’s your entertainment value!

The real problem is that the source material is just too episodic to ignite into an effective opera. One thing follows another, yet there are no compelling characters or through lines. But there is a dance of page boys and dwarves and clowns: There’s your entertainment value!

You have to hand it to French grand opera: Here’s a form with a better than 50 percent failure rate among the greatest and most successful opera composers of the 19th century. That’s a pretty special record.

6. Natoma

(Indian Kitsch Division) Early attempts at writing an opera on American themes produced a lot of faceless flops from long-forgotten composers. But in the general wreckage, Victor Herbert’s Natoma is especially noticeable, not just because its 1911 premiere at the Metropolitan Opera was hyped to the max and cast with stars (Mary Garden and John McCormack), but mainly because its libretto is so sensationally execrable.

Everything is wrong with Natoma: There’s not one natural moment in it, from the prissiness of the lovers (“One kiss upon those tell-tale eyes”) to the laughable imitation Longfellow in which Natoma is forced to speak:

-

Soon there came an awful famine,

And his people paled with hunger,

Paled with hunger and the famine.

Then he went down to the ocean

Where the waters roll unceasing,

And he prayed unto the Spirit,

To the Spirit of the mountain,

To the Spirit of the waters.

As another cartoon Native American might have put it: “Ugh!”

The libretto is impossibly wordy (“methinks that if the young lieutenant from the big ship asked you to his wigwam, you would not say him nay”), and, with all the big set pieces it features, there’s barely time for any action at all. In fact there is only one action: Natoma foils an attempted kidnapping by killing the kidnapper. This scene has no fallout or consequence. The entire third act is a set-piece church scene in which Natoma gives the lieutenant (her former lover) and his new love an amulet and then walks out of the church. So go ahead, make up your own ending. (An earthquake, and then Natoma’s grandfather emerges from the crypt smiling and holding a Wii console…).

Natoma was a legendary flop, so much so that The Music Man composer Meredith Willson, who was not yet 9 years old when the opera premiered, included an account of it in his autobiography. Herbert, thankfully, took some time off from the composition of his grand opera to write Naughty Marietta (1910), then survived the wreck to write a few more hit operettas.

(The final five terrible librettos will be dealt with in the next issue.)