Until the demise of Jerry Garcia in 1995, gigging as one of the legendary Grateful Dead’s guitarists, vocalists, and songwriters was a reliable source of both income and inspiration for Bob Weir. Now Weir has a new dream: writing for and performing with orchestras, in concert halls. The dream will be coming true close to Weir's home base here, despite a delay.

Last weekend was to have witnessed First Fusion, a unique amalgam of rock and classical musics. It would have positioned Weir and several trusted colleagues on stage at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium with Alasdair Neale and the Marin Symphony and several subsets of classical musicians, including Quartet San Francisco. The program would have included Weir’s resettings (with help from local composer-arranger Giancarlo Aquilanti) of favorites from the Dead canon, as well as new Weir songs and improvisations.

But the concert has been postponed and is expected to be announced in 2011. All the musicians remain on board.

Weir is making good use of the extra time, coming up to speed with arranging for ensembles of nonrock instrumentation and with deploying state-of-the-art technology to create those arrangements. His bag of musical tricks has expanded to include Pro Tools, the digital audio computer program; the Vienna Symphonic Library, which provides online orchestral sound samples; and the Ztar, which looks like a stringless guitar and functions as a MIDI interface between the player and Pro Tools. And Weir is constructing a new studio in San Rafael, due to open this winter, which will function both as his laboratory for further experimentation in rock, classical, and film music genres, and as a “production facility for broadcasting,” for “anyone who wants to put something out over any medium.”

Classical Role in Classic Rock

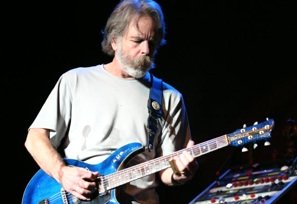

In the gated aerie high above Mill Valley that he’s called home during most of the Dead’s run and after, the bearded and ingenuous 63-year-old Weir spent a breezy hour with Classical Voice, showing off his modern equipment but also harkening back to classical influences on his music. His adoptive parents “weren’t much into music,” he remarks, but “I remember, when I was 4 years old, listening to records by Enrico Caruso. I was totally swept away, and from that point on, there was no question in my mind about what I wanted to do: I wanted to play and sing for a living.”

His potential was groomed by a teacher at the boarding school he was sent to in Colorado Springs. This mentor “pretty much identified me as a musician, and he used to take me aside and play me stuff, Berlioz and late Romantic or early Impressionistic stuff. I loved Debussy, Ravel, those guys — the dreaminess, the fact that you could go anywhere. And through the Romantic era, at least to my ear, a lot of the music was oftentimes elaborations on folk music. But these guys started doing splashy stuff with it, tonal clusters or textural stuff that was new. And it was dreamlike.”

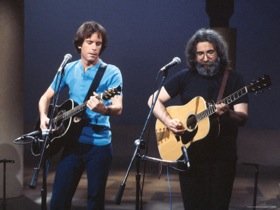

When Weir “left home at 17 or 18 and ran off with a rock ’n’ roll band,” he hadn’t had any formal musical training, but he “learned through doing.” And he discovered that his goals of sourcing folk music and of dreamy elaboration were shared by his Grateful Dead bandmates, who at first included guitarist and banjo player Jerry Garcia, bassist Phil Lesh, keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, and drummer Bill Kreutzmann (later joined by a second drummer and percussionist, Mickey Hart).

As they evolved as one of rock’s first jam bands, and began to accrue a huge, devoted fan base during the high times of the late 1960s and early ’70s, did the Dead ever discuss classical music? “Hell, yeah. — ‘What are you listening to these days?’ ‘I particularly dig this part of what this guy’s doing here.’ — then we’d go back, and if Jerry told me something or Phil told me something, I’d go listen to it, particularly for their insights into whatever they were talking about, and within a few days it would be happening for us on stage.

“Somewhere along the line,” Weir continues, “I developed this facility where I could pretty much play what I’d been listening to, if you could do it with five fingers on your left hand. For instance, one night I discovered Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, and the next day I just sat down and wrote an ascending chord sequence that was reminiscent, to me, of that. And I worked with a lyric with my friend Gerrit Graham and came up with Victim of the Crime, which is a sort of a controversial song in Dead lore, an edgy lyric and an edgy musical presentation, maybe a little too edgy for some folks.”

In their basic song structure and choice of tunes to cover, the Dead were also beholden to folk sources, and, in their elongated jams and improvisations, to jazz and North Indian classical music. “We were hungry for any kind of music from anywhere,” Weir recalls. “On a good night, we were probably doing [Indian] ragas. We could hear the declarations from the heavenly bodies, if we relaxed and just let ourselves go there, and be there when we found the right notes, right chords, right relationships.”

Riding the Orchestral Wave

Weir has helped keep the Dead spirit alive with periodic reunions of the band, and with related small ensembles, including RatDog, formed with bassist Rob Wasserman, and Furthur, spawned by Weir and Phil Lesh. Wasserman and drummer Jay Lane also joined Weir in the group Scaring the Children, and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti has served in several of these groups. Weir hopes that Wasserman and Chimenti will be there to partner him in the rescheduled First Fusion, and he senses great potential in a more direct connection to the classical world.

“If you’re working with an orchestra, suddenly you’ve got a whole lot of colors on your palette, some that you just can’t get with a traditional rock ’n’ roll ensemble,” says Weir. “Strings are good for a lot of stuff; they’re particularly good for dissonances. But I don’t want to lean on ’em too heavily — it’s not gonna be ‘The Grateful Dead with 101 Strings.’” Collaborating with Robert Hunter, the stalwart Dead lyricist with whom he worked on such Dead hits as Sugar Magnolia and Truckin’, Weir is writing new songs that may be showcased in First Fusion. He’ll enhance the orchestra with some among his dozens of custom-made guitars, as well as his sweet and mellow baritone vocals. “It won’t be quite opera,” he chuckles, “but I’m expecting to catch a pretty huge wave.”

Weir has been careful about selecting members of the Marin Symphony with whom he can effectively interact in small ensembles in the first part of the anticipated program. “A lot of symphony musicians don’t improvise; they’re technicians and they play what’s on the page,” he points out. “What I want to look for is people with wings, with ears and wings, and I’ve found some.”

Beyond Marin, Weir will look to classical hook-ups across the country, which he’s investigated while touring with RatDog and Furthur. “We play a lot of sheds, and some of the sheds are nice ones, and in those nice ones, someone from the board of directors will show up, and word has gotten around that I’m up to this [classical fusion]. ... So I may do a run next summer to places like Tanglewood and the Mann Center [in Philadelphia], and use their pops orchestras, for the purpose of getting new butts in the seats.”

That’s also a prime directive for the Marin Symphony, and Weir is committed to “bringing in some people to help with funding and marketing” to ensure that First Fusion succeeds next year. He also hopes to deploy his new and exciting “patent-pending method of recording ... so that you’ll be able to buy a recording of that evening, that evening.” Concertgoers who pay extra for a wristband on their way in will be able to walk out with a CD that has captured the event by matrixing audio from the soundboard with input from a couple of high-quality condenser microphones. “You’ll get the sweetness of the room and a little bit of crowd reaction,” Weir promises.

And he won’t be surprised if that crowd includes both Deadheads and classical diehards. “Some of those folks are gonna be saying, ‘Holy Jesus, I didn’t know a symphony could do that!’ And for those for whom it’s their first symphonic experience, they’ll be blown away, and they’ll say, ‘I’m gonna go back and hear Beethoven! This is good stuff!’”