In the summer of 1960, Chris Strachwitz was driving through rural Texas, searching for down-home blues musicians to record, when he came across some folks chopping cotton in a field outside Navasota.

“You know any good guitar pickers in these parts?” asked the tall, sandy-haired schoolteacher, who’d gone mad for jazz and blues after immigrating to the U.S. from war-ravaged Germany when he was 16.

The farmhands directed Strachwitz to Navasota, where he discovered the legendary singer and picker Mance Lipscomb, a 65-year-old sharecropper with a vast repertoire of blues, reels, popular songs, and spirituals. Lipscomb had never made a record, or ventured beyond Navasota, until Strachwitz showed up with his tape machine. Mance Lipscomb: Texas Songster and Sharecropper was the first album Strachwitz put out on Arhoolie Records, the renowned roots-music label that over the last 50 years has captured, culled, and released a rich range of vernacular music: country blues, folk, Cajun, zydeco, hillbilly, and Tex-Mex music, plus the sounds of New Orleans brass bands and Hawaiian steel guitar.

“I love music that’s fierce and raw. I don’t like slick stuff,” says the now-silver haired, 79-year-old Strachwitz, an omnivorous music collector who preserved a large chunk of authentic American and Mexican folk music that might have disappeared if he hadn’t been so passionate about recording and collecting it.

Great Music Off the Beaten Track

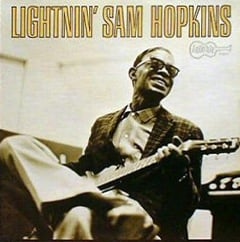

His journeys through the South in the 1960s brought forth a slew of great recordings by bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mississippi Fred McDowell, zydeco master Clifton Chenier, the fiddle-playing country singer Rose Maddox, and others. In the early ’70s, Strachwitz delved deeply into the rousing accordion-based Tejano and norteño music he heard on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border. Among others, he recorded the leading Tex-Mex accordionist Flaco Jiménez and the towering Tejano singer Lydia Mendoza, both of whom appeared in Chulas Fronteras, the classic 1976 documentary Strachwitz made with Bay Area filmmaker Les Blank.

“I only recorded what I liked,” says the producer, a forthright gent with a keen ear and generous spirit. “Record companies record anything that’s commercial. I always had slow-selling, long-playing records,” he adds with a laugh. He’s sitting in his cluttered office at Arhoolie’s El Cerrito headquarters, making arrangements for the three-day Arhoolie 50th birthday bash at Berkeley’s Freight & Salvage Coffeehouse, Feb. 4-6.

Featured Videos

An excerpt from No Mouse Music!, a documentary about Chris Strachwitz' Arhoolie Records

Excerpts from a 1963 German TV documentary on American roots music featuring Arhoolie Records founder Chris Strachwitz

A fund-raiser for the Arhoolie Foundation, the celebration features scores of musicians — including big-name Grammy winners like guitarist Ry Cooder and bluesman Taj Mahal — who have been associated with the label and its beloved founder over the last half century. They span the spectrum of styles Strachwitz has championed.

Cooder, who found his path at 13 after hearing the explosive music of bluesman Big Joe Williams on an early Arhoolie recording, headlines the sold-out Friday night show. The bill also features accordionist Santiago Jiménez Jr. (the brother of Flaco, with whom Cooder recorded two Arhoolie albums), and Any Old Time String Band, among others.

The festivities continue on Saturday night with a blast of Cajun, jazz, and jug band music: the Savoy-Doucet band, the Creole Belles, trombonist Bob Mielke’s All Stars with the venerable jazz and blues singer Barbara Dane, the Washboard 3, and the Tremé Brass Band from New Orleans. The party gets going at 4 p.m. in Berkeley’s Civic Center Park, with the Tremé band leading a second-line parade to the Addison Street club.

Taj Mahal on His Arhoolie Inspiration

Topping the Sunday night bill will be Taj Mahal, heard alongside the down-home southern sounds of Suzy and Eric Thompson, the sacred steel guitar of the Campbell Brothers (music from the African-American Pentecostal church), the traditional Mexican music of Los Cenzontles, and folk-rocker Country Joe McDonald, whose anti–Vietnam War anthem, I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die, was recorded in Strachwitz’ Berkeley living room. The royalties helped the record producer buy the El Cerrito buildings that house the Down Home Music store, Arhoolie, and his vast collection of 78s, 45s, and LPs.

“Chris and Arhoolie have been hugely important to the culture,” says Mahal, who became a fan of the fledging label in 1960 when a fellow University of Massachusetts music student played him Mance Lipscomb’s record.

“It was exactly what I wanted to hear at that moment,” says Mahal, who drew inspiration from many other Arhoolie artists, among them Lightnin’ Hopkins, Fred McDowell, and K.C. Douglas, whose Mercury Boogie later became another source of royalties that kept Arhoolie afloat. “I was introduced to norteño music through Chris, and his Clifton Chenier recordings even got me to like accordion. Chris has always gone for the real stuff. It was wonderful to see someone totally dedicated to this great music.”

Linda Ronstadt Remembers

While singer Linda Ronstadt isn’t performing at next week’s bash, she will appear on a panel discussing “Mexican Music and Beyond.” She’s on the Arhoolie Foundation Advisory Board, along with Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt, and other stellar artists who’ve been inspired by the music on Arhoolie. Ronstadt became aware of the label in the early ’70s while touring with Jackson Browne and David Lindley.

“We’d be on the bus, and every morning around 6 a.m. David Lindley, who slept in the luggage rack, would get up and play Clifton Chenier’s music, really loud” Ronstadt recalls. “We loved it so much we didn't mind. That was my introduction to Arhoolie, as a source of Cajun and zydeco music.” The singer, who grew up listening to and playing Mexican and Mexican-American music in Tucson, praises Strachwitz for seeing the music’s value and shining a light on it. The Arhoolie Foundation is in the midst of digitizing his peerless collection of Mexican and Mexican-American recordings — some 50,000 discs. Later this month, locals will be able to hear the music in the collection, which has been given to UCLA, in a listening booth at Down Home Records.

“We were delighted that somebody else liked and validated and shared our passion for this music,” Ronstadt says. “There’s nobody like Chris. There’s a musical energy around him; whatever he’s interested in, there’s a beating heart in the middle of it. What he’s done is vast.”

Seeking the Wellsprings of American Music

Strachwitz didn’t set out to preserve American roots music, or think of what he was doing in those terms, when he began recording musicians in Houston beer joints and Mississippi shacks.

“I was just a fan,” Strachwitz says. “I thought I was catching some really neat stuff. I loved meeting these people. It was an adventure. It was like a safari. Rich people would go hunting. I didn’t have to kill anything: I just hunted music and records.”

He’d recorded music off the radio, and the work of musician friends like bluesman Jesse Fuller, while studying at UC Berkeley in the late 1950s. “I just loved to record. I thought this was the most amazing invention ever made,” says Strachwitz, who went to Houston in the summer of 1959 to find his idol, Lightnin’ Hopkins.

“That started a pilgrimage for me,” says Strachwitz, who vividly recalls hearing Hopkins in a tiny beer joint called Pops’.

“Here was this guy ferociously blasting away on this electric guitar with just a drummer behind him, singing about how his shoulder was aching and he couldn’t see the road because the chuckholes were covered with water. Then he just pointed at me and said, ‘Whoa, this man come all the way from California just to hear po’ Lightnin’ sing.’ Then he started singing about the woman in front of him. It was like a goddamned conversation. When I left, I told [Texas folklorist] Mack McCormick, ‘I gotta start a recording company to record this man in these beer joints.’ I wanted to get that immediacy.”

Strachwitz returned the next year with his tape machine, but Hopkins wasn’t in town. With the help of McCormick — who suggested he call the label Arhoolie after an old field holler — he found Lipscomb, as well as other old-timers like bottleneck guitarist Black Ace.

“We just started playing detective,” Strachwitz says. He asked the attendant at a filling station outside Lafayette, Louisiana, where people played Cajun music. The guy didn’t know but directed him to the bars in town. He walked into one to find an attractive young female bartender.

“I finally got up the nerve to order a beer and ask her if she’d ever heard any Cajun music,” Strachwitz recalls. “She just broke out laughin’ like hell and said, ‘Oh yeah, just last night me and my boyfriend got drunk and went out to the Midway Club. You’ll hear plenty of it there.’

“So I drove out, and I’ll never forget the sight of it: these little men with these huge women moving counterclockwise around this big dance floor. And this band was playing my favorite song, It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels. One guy sang it in French and another guy sang it in English. And I said, ‘Oh my God, this is unbelievable.’ You know, when you hear this kind of s---, either you hate it or love it. I was totally enamored of it.”

Strachwitz couldn’t have imaged that Arhoolie Records, his all-consuming hobby, would last half a century. He didn’t think he’d live this long, he says with a laugh.

“It’s been an amazing journey. I had fun. I’m glad I caught something people like. I always knew these were audio snapshots that can never be repeated.”