“Music is a fundamental human right.” — Gustavo Dudamel.

There are times when natural phenomena can cause a compass to swing crazily from pole to pole, making navigation almost impossible. That is the situation that orchestras and opera companies throughout the country find themselves in as a result of the coronavirus pandemic: there is a dawning awareness that since no one knows what the future will look like, there’s also no way to know what it will take to survive, and how long it will take to get there.

According to Chicago-based arts consultant, Drew McManus; Jesse Rosen, President and CEO of The League of American Orchestras; Marc A. Scorca, President and CEO of Opera America; and Deborah Borda, CEO of the New York Philharmonic, the initial impact of the pandemic shutdown was a nation-wide wave of panic. But as inter-organization communication has increased the atmosphere has shifted to one of strategically focused long-term planning, instead of, as McManus puts it, “planning 20 minutes into the future.”

The problem was succinctly defined by Deborah Borda on May 5, during the opening session of the League of American Orchestra’s annual (now online) conference.

“How do we make decisions about a future we don’t understand? There are a number of challenges we are going to have to face, particularly in the absence of a coherent national policy about social distancing, testing, and contact tracing as a re-entry strategy. So we’re out there on our own.”

As expressed by Jesse Rosen, “Organizations are being forced to plan and be ready to implement multiple scenarios, which is unusual for an art form that has traditionally been able to rely on a consistent performance template. It’s requiring orchestras to face very difficult decisions and have the courage to engage with patrons and subscribers directly and honestly. Transparency is going to be critically important.”

In order to return to the concert hall, Borda feels, the first priority has to be safety— for audiences, staff, and musicians. But if a return also requires social distancing, that will present a serious economic reality.

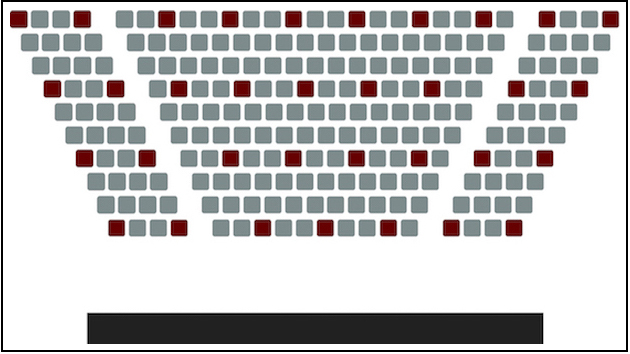

“We ran a model for David Geffen Hall using the CDC guidelines for social distancing,” Borda explained. “The hall has 2,700 seats. We found we could bring 380 people in! I didn’t believe that because it was such a discouraging number.” But when Borda contacted her counterparts at Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center she found they had run a similar model and come up with the same disastrous results.

There is, however, a proposal that could significantly alter those figures, said McManus. It’s called “pod seating,” which would allow families or couples that are cohabitating to sit together. How the liability issues surrounding pod seating would be handled is another question.

I asked McManus what he thought the signposts were that would allow a return to the concert hall.

“I think now is the wrong time to be asking that question,” was his response. “Many people say they won’t feel comfortable returning to the concert hall until there is a vaccine. Right now, we are still in an information desert when answers are being driven by existing information and fear. If you’re looking for signs on the road to recovery they’re going to be marked by improvement in the amount of reliable information. That’s what will change audience responses combined with the psychological effect. You can’t stay locked down forever, but it may come down to a balance of risk and liability. And it all touches on the political environment, especially at the presidential and state level. The dangerous trap to avoid is anything that makes people feel more anxious, even if it means opening later.”

In fact, the first test of a live-concert in the U.S. was to have taken place May 18, with a socially-distanced performance by country singer Travis McCready at TempleLive in Fort Smith, Arkansas. However, on May 12 the state’s Republican governor, Asa Hutchinson, announced the state’s health department would be issuing a cease-and-desist order for the concert due to the extension of the state’s coronavirus lockdown measures.

Had the concert proceeded, it would have taken place in a hall with a capacity of 1,100 reduced to 229. The audience would have had their temperatures taken when they arrived, been directed to their seats along one-way walkways, with a limit of 10 people in the bathroom at any one time. Seating would be in “pods,” defined as “small gatherings restricted to friends and relatives comfortable with sitting together.” Each group, between two and 12 in number, would be seated together while the rest of the audience sat six feet from one another other. In addition, the concert’s Ticketmaster page said TempleLive planned to sanitize the venue using fog sprayers and would require masks to be worn by the audience and staff. The three-member band would maintain social distancing onstage but had not planned to wear masks.

Even with these limitations, the concert was sold out. Would it have been a preview of coming attractions?

Getting Together From Home

As this article was being prepared and published the League of American Orchestras is continuing its monthlong annual conference, through June 12. The topics under discussion cover a wide range of topics among them: “Scenario Planning in the Time of COVID-19”; “Philanthropy in Transformational Times”; “Engaging Audiences at Home”; “Outside the Box: An (Unconventional) Orchestra Musician’s Perspective”; “Surfing the Digital Wave”; “Increase Your Orchestra’s Footprint in Local and Global Arenas”; and “Addressing Gender Equity On and Off Stage.”

According to Jesse Rosen, over 2,020 people registered to take part in the League’s online event. “That is more than double what we’ve ever had at a conference before,” he said. The registered attendees include managers of professional and youth orchestra, musicians, conductors, CEOs, composers, music publishers, marketing managers, and artist managers. It is a gathering that Rosen sees as a real “positive” and an indication of how successful digital outreach can be.

Another example of the expanding realm of online interaction will be the four-week conference organized by Opera America that began on May 13 and runs through June 3. The themes for each of the four weeks include: “Having a Vision for the Future” (moderated by Anne Meier, Director of Music and Opera, National Endowment for the Arts); “New Technologies and Their Impact” (from innovations in lighting to HD transmission); “Creating Real Belonging” (facing questions of diversity); and “Making Change” (innovating business practices to meet cultural/economic changes).

Ever since the pandemic struck, McManus said, the demand for the tech support side of his company has gone through the roof. “Organizations and individuals have needed a substantial amount of help.”

Many organizations that had planned to make technological improvements to their web platforms and online presence in the future have pushed those projects forward because their ability to maintain brand presence and connect with patrons now relies almost exclusively on their internet profile — whether it’s streaming past concerts, in-home performances, educational webinars and podcasts, or clever events like Mainly Mozart Festival’s five o’clock Happy Hours on Zoom, which comes complete with a designated drink of the day.

The problem, McManus observed, is that this rush to find a spot on the internet has led to a digital glut of competing programming.

“This shotgun approach,” he said, “is self-defeating. The trick is to find a strategy that avoids that trap. The first thing you have to do is create really worthwhile content presented on an attractive delivery platform. Then when you’ve established your audience you can focus on click-through rate analytics to divide subscribers into specific topic groupings. It’s a way to maximize brand presence with content targeted to specific topic groups like patrons and educators.”

Orchestras are also facing the issue of whether, at this point to continue to sell season ticket subscriptions, forcing patrons to make what McManus describes as a “Sophie’s Choice”: pay now for a season that may not take place in order to secure your seat(s) or wait until a time when the return to the concert hall is assured, though you will have had to sacrifice your current seats.

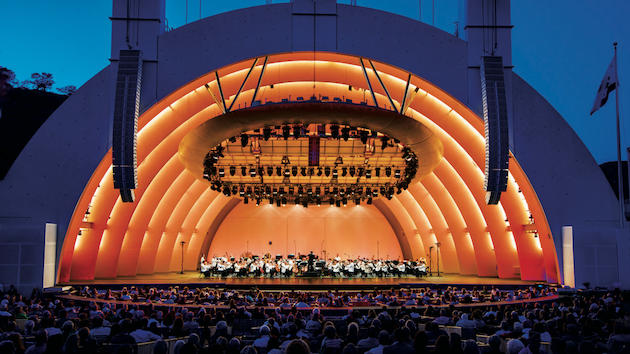

Selling subscriptions now is risky, as the real possibility exists that seasons may be canceled, a recent example being the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s decision to cancel its (economically crucial) summer season at the Hollywood Bowl, resulting in layoffs and a reported $80 million budget shortfall.

And then there is question of refunds. Many long-term subscribers may be willing to accept rainchecks for canceled performances or even turn their tickets into a donation. But the potential for mass refunds is a real possibility.

If symphony orchestras face complicated issues surrounding re-opening, the equation becomes vastly more complicated for opera companies, which must face the challenge of social distancing for an art form that thrives on emotional proximity: the ability to rehearse singers, orchestra, chorus and dancers. Then there is the question of how to open scene shops, costume shops — that’s all before you can get onstage.

These are the issues that Marc Scorca and the organization he leads, Opera America, have been confronting.

“Our members are not producing, but Opera America is over producing,” Scorca explained. “We’re a service organization and this is a service organization nightmare. We were not prepared for all our members to be emailing and needing us at the same time as the panic set in. There was a sense of overall bewilderment about what to do next. Since then we’ve gone from panic to a relative state of calm — not because our members are not upset, they’re definitely stressed. But now we’re facing a new reality squarely in the eye and figuring out how to navigate it. There is uncertainty, but there is also clear-headedness.

“We held our first set of conference calls on March 16. Since then we have done an average of 20 video conferences a week focused on general directors, development and marketing personnel, professional, education, artistic administration, you name it.”

As the shutdown continued, Scorca said, Opera America found itself pivoting to become a networking, clearing house for information and interconnectivity. “Our members are now in closer contact than ever existed before. Our prime topics of concern have turned to issues involvement government relief packages, contract obligations, the implications of force majeure, electronic media rights, and advocacy.”

As with orchestras, Scorca stresses the need for multiple scenario planning — for good and for bad.

“Every organization has to invent a plan for what they hope will happen, and a plan for what’s least likely to happen, because that’s the plan you may be forced to live with. Our goal is to keep our members unified and informed. It’s not just about getting through this crisis, but what it will look like on the other side. It’s not a happy picture.”

CORRECTION: The ending date for League of American Orchestras conference is June 12, not May 29, as originally reported.