Prompted by an article in The New York Times about doctors who volunteer their services at the Metropolitan Opera, I looked into the situation in San Francisco and found a mother lode of fascinating medical-musical lore.

The story at the Met:

Dr. Jenny Cho is one of several physicians who act as the Met’s doctor on call, each serving once a week in exchange for a free night at the opera and the chance to spend time near singers they admire. The doctors’ job is not only to minister to the strained larynxes and occasional fractures of the cast and crew, but also to treat members of the audience, who are most commonly felled by pre-performance overindulgence in wine and rich restaurant food.

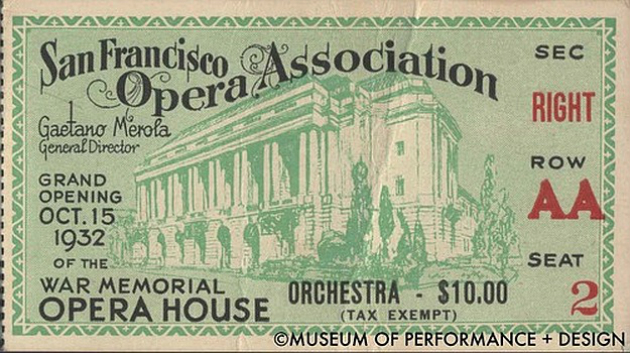

In San Francisco, similar arrangements go back a long time, perhaps to the inauguration of the War Memorial Opera House in 1932 with Tosca. The late oncologist Dr. Ernest Rosenbaum started volunteering in the 1960s, continued for more than 40 years, and at one time led 17 physicians taking turns in volunteering. One of them was Dr. Myron Marx, of the California Pacific Medical Center, who is now the Opera's "Company Doctor."

San Francisco Opera publicist Julia Inouye explains the logistics of the arrangement:

The on-call show doctor volunteers his/her time at each performance and is seated in comp seats on the aisle at the back of the house for easy access. Dr. Marx volunteers his time, and he assigns the on-call doctors for every performance, he also donates company-wide flu vaccinations and round-the-clock phone consultations). Dr. Marx provides us with the doctor's bag/medical supplies for use by the on-call show doctor. When the show doctor arrives, he or she checks in with the Rehearsal Department and his/her seat number and cell number are confirmed; the doctor is also given a backstage credential and a pager at that time.

All large performance organizations employ an Emergency Medical Technician in addition to volunteer doctors. In the War Memorial, for the Opera and San Francisco Ballet, the EMT's office is in the basement; for the San Francisco Symphony, the EMT is on street level at the Van Ness entrance (between the elevator and women's rest room). Volunteer doctors for the Symphony at times accompany tours, but are not regularly in the house. A Ballet spokesperson says "We have paid EMTs and doctors that we can call, but no doctors physically at the Opera House for the performances."

Dr. Marx is very much present physically for his beloved opera company, with vivid memories of from years passed:

In 1987, during a live performance at the War Memorial Opera House, a baritone collapsed on stage in a crowd scene, while others were singing, and was carried off by his colleagues. I rushed backstage and asked if they needed a doctor and I was taken to the stricken singer's dressing room.

He had fainted and the staff had him propped up in a chair and were putting water on his face in an attempt to revive him. The man looked liked he had fainted, and the best way to revive someone from a faint is to place them on on the floor on their back and lift their legs up, which was done. Twenty minutes later this singer was able to return to the performance, which had continued in an uninterrupted fashion with audience being unaware of what had just transpired.

Then-General Director Terence McEwen and Artistic Administrator Sally Billinghurst were appreciative. Two weeks later I rushed backstage again when I saw another mishap on stage. This time a soprano clearly sprained her ankle and had to limp through the remainder of the act. The ankle was examined, there was no fracture, and it was wrapped for support and she continued until the final curtain.

At the request of McEwen and Billinghurst, Dr. Marx went to work, volunteering. In opera, he says, the singers' instrument is their body and they are quite in-tune with it and appreciate the easy access to a physician while they are in town and especially before a performance. "If I cannot handle their particular medical problem between performances, I rely on my access to the medical community to get them seen in a timely fashion by the appropriate specialist in a way that interferes the least with their professional duties and obligations."

Going beyond his title of "Medical Adviser to the San Francisco Opera," Dr. Marx also administers about 250 flu shots every year, helping to prevent more work for doctors.

At the Met, where there have been numerous on-stage injuries recently and a dangerous situation walking on and sliding down the last Wagner Ring cycle's 45-ton sets, Dr. Cho revels in her volunteer work: "A bad day at the Met is better than a spectacular day anywhere else.” She has been through many bad/spectacular nights, having treated patrons for heart attacks, stagehands for back strain or even broken bones. An ear, nose, and throat specialist, she is very popular with singers especially.

But during performances, she also listens for noises from the nearby standing room gallery, indicating when a patron faints. "I can hear the thud,” she says.