Every Wagner fan dreams of a trip to the Bayreuth Festival, a pilgrimage to hear Richard Wagner's operas in his very own opera house, the Festspielhaus, complete with its famously beautiful acoustics, notoriously uncomfortable seats, and lack of air conditioning. I was lucky enough to obtain tickets this year to all of the productions, seeing seven operas in eight days.

These were Frank Castorf's production of Der Ring des Nibelungen, conducted by Kirill Petrenko, the incoming chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic; a new Tristan und Isolde, by Katharina Wagner, the composer's great-granddaughter, conducted by Christian Thielemann; Jan Philipp Gloger's Der fliegender Hollander, conducted by Axel Kober; and the very last performance of the famous “rat” Lohengrin, production, directed by Hans Neuenfels and conducted by Alain Altinoglu.

The productions are all set in some more or less current time period, with cars, rolling luggage, subways, hypodermic needles, electric fans, above-ground swimming pools, and oil wells on stage, and the performers in modern dress. After seeing them, it's clear to me that what counts in such productions is not the scenery, costumes, and props, but how close the director is able to come to the emotional heart of the operas, as expressed in the Personenregie (direction of the individual performers). As in any opera production, the purely musical success depends largely on the conductor and the singers.

Of the seven operas, surely the most unified and dramatically effective was Neuenfels' Lohengrin, which has become something of a Bayreuth classic in its several bring-ups. I had seen some photos from the production since its debut in 2010, showing the principal singers in modern dress and the chorus in rat costumes, but none of that prepared me for the mysterious beauty of the whole.

The production uses an abstract, starkly sterile unit set, all black and white, with only the chorus costumes and a few props in other colors. There is no sense that there might be a natural world anywhere. The presence and behavior of the rat-costumed chorus reinforces this sense. Sometimes they're in black rat costumes, sometimes white; a group of rat-children wears pink. The chorus members constantly rub their rat-paw prostheses together or groom their rat-heads. At one dramatic juncture, the men step out of their rat costumes and underneath they're wearing safety-yellow formal dress. Later in the opera, the female choristers appear in pastel dresses and hats … trailing rat tails behind them.

The effect is strangely charming despite the sinister implications of the rest of the staging: Are the characters trapped in lab? Or an insane asylum? At one point, supernumeraries dressed in blue lab outfits appear and inject a couple of unruly rats with...what?

The behavior of two of the principal characters reinforces the sense that the opera takes place in an asylum. King Henry is strangely craven, cringing and sometimes afflicted with tremors. He also needs to be managed by his Herald.

Elsa appears to be truly disturbed, and physically afflicted as well. She staggers around as if she has incomplete control of her feet and legs. She enters dressed in white and punctured by numerous arrows, St. Sebastian-like, perhaps suggesting the torture inflicted on her by the suspicions that she has killed her brother. When she challenges Lohengrin after their wedding, she fears him, and her fear seems to go beyond her legitimate concerns about who he is and into a more existential fear of emotional and physical intimacy with another human.

Neuenfels' brilliance goes well beyond the physical production and its various symbols, to beautifully detailed direction of each singer. Their movements were always economical, yet the emotional intention was powerfully projected. And Neuenfels had singers fully able to execute his vision, most of whom had appeared in the production before.

What does it all mean? Well, I don't really know: It could be about the mindlessness of rodents in a lab, or of average people in a political machine. (Germany certainly had plenty of experience with those in the 20th Century, between the Third Reich and Soviet control of East Germany.) It could be some kind of fantasy in the hearts of madmen in an asylum. Regardless of your interpretation – and you can see this production on video with almost the same cast – it's a great theatrical experience.

I've long been aware of and curious about Klaus Florian Vogt, who sang Lohengrin. He has a voice of unearthly beauty, with a sweet timbre and grace that bring to mind trecordings of John McCormack, from early in the past century, more than any other tenor. And yet, in the grateful acoustic of the Festspielhaus, this Mozartean voice had all the power and projection needed for the swan knight. Add to this his physical beauty and superb acting – you could hardly take your eyes off him - and you have a dream Lohengrin.

Annette Dasch, singing Elsa, doesn't have nearly as distinctive a voice as Vogt, but she gave a performance of great dramatic depth and conviction, from Elsa's hopes and fears to the collapse of her dream. Petra Lang's Ortrud is rather terrifying, in a good way: intense, creepy, full of hate. Vocally, she sounded better than in the same role in San Francisco, but she also seemed under some stress by the end of the performance. It remains to be seen how she will handle the much longer role of Isolde in next year's Festival.

Jukka Rasilainen made an unusually strong Telramund, less abject than usual, and sang with great tonal beauty. Wilhelm Schwinghammer was a memorably neurotic Heinrich, Samuel Youn an excellent King's Herald. The Bayreuth chorus, a mighty group, sang superbly, with near-perfect unison and beautiful tone. Alain Altinoglu's conducting had poise, balance, and a great feel for the music at both its grandest and most intimate, in a direct and natural way.

At the close of the performance, the audience went more or less crazy, giving the cast and crew, and Neuenfels himself, the greatest ovation I have ever heard. The cast and conductor deserved every last minute of that ovation.

The greatest part of my time in the Festspielhaus was, of course, taken up with Castorf's Ring production, which was performed for the third time and will be revived in 2016. This production has been variously characterized as a mess, anarchic, and anti-directorial. I can certainly understand why, but I am going to call it complicated. So much is going on in the production that I don't believe anyone can take it all in with just one viewing. I didn't exactly like the whole, because a great deal of it is rather far from our usual conception of the libretto and the music, but Castorf certainly gives his audience plenty to think about. I hope that the Festival is filming this production, because I'd like to wrestle with it further.

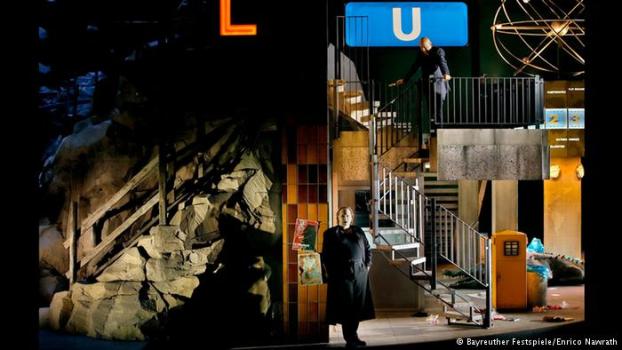

Castorf, born and raised in East Germany and trained originally to be a railway worker, has created a Ring production that's deeply connected with political history and his own origins. A gigantic frieze that's clearly modeled on Mount Rushmore looms over much of Siegfried, but instead of presidents of the United States, the sculpted heads are Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. He incorporates a subway entrance and clock from Berlin's Alexanderplatz into the same opera.

In Die Walküre, an Azerbaijani oil well is the set for Hunding's house and Valkyrie rock. A sign marking an industrial city, famous in East Germany, dominates one Götterdämmerung set, and in the same opera, a baby carriage bumps down a staircase and spills a load of potatoes, a scene straight out of Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin.

Castorf's approach is to focus tightly on just one or two aspects of the operas and their characters. You won't find much in this production of the natural world, or of the magic and majesty portrayed in most Ring productions. The director largely omits dragons, craggy mountaintops, rainbow bridges, and the like. Almost the only typical effect is the thunder and lightning in Donner's call to the mists.

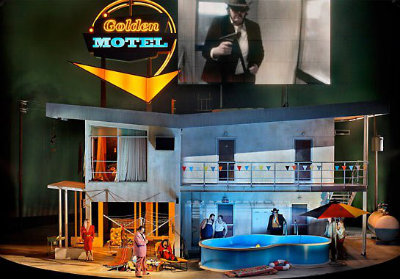

In Das Rheingold, set primarily in and around the Golden Motel, the Rhinemaidens are vicious floozies who torture, rather than tease, Alberich. The gods are gangsters, with little of the noble stature implied by Wagner's music. This isn't an unreasonable proposition, given Wotan's trickery and desire for power. Castorf's staging of the opera is exceptionally complex, with the action unfolding on three separate levels of the motel and with each character assigned an immense amount to do.

For example, before the gold is measured against Freia, one of the gods nearly tears apart an upstairs bedroom in the motel, breaking a window and tossing bedding, pillows, and the mattress out the window frame. Then Freia is dragged upstairs, nearly raped, thrown on the bed while several other gods crowd into the room, and covered with the gold. Meanwhile, as is the case throughout the cycle, live cameras capture what's going on in the motel room and some of the action elsewhere in the motel, and the video streams are projected onto screens set on the room of the motel.

Especially in Das Rheingold, this is rather exhausting for the audience. The live action and video streams both demand your attention, with the video, and other stage action, sometimes commenting on and sometimes adding to what's prescribed by the libretto.

Castorf adds another layer of complexity by including a silent actor who has his own script to follow. This character appears in all four operas; he manages the store in the gas station next to the Golden Motel and takes various other parts later in the Ring. He represents Everyman, and as such, he is regularly abused by Wagner's characters, who represent The Powers That Be. He stands in for the bear in Siegfried. He's beaten, chased around, and finally murdered and stuffed in the trunk of a car in Götterdämmerung.

The director places Die Walküre in the Azerbaijani oil fields, on which the Soviet Union had significant economic dependence before the dissolution of the USSR. Hunding's “hut” is a huge structure surrounding an oil well. The tender scenes between Sieglinde and Siegmund take place outside the structure, while the dinner confrontation among the three characters is on a deck high above the stage. The video feed is used to show Sieglinde making nice to Hunding in a room not visible to the audience, then drugging him.

Valhalla is an oil-processing facility, with various machines and samples of oil visible behind the action, as well as supernumeraries working in the facility. Castorf stages the long dialogs and monologues of Acts II and III fairly conventionally. His interpretation of the relationship between Wotan and Brünnhilde is unique in my experience. You might think that Wotan hates his daughter, because there is no tenderness anywhere in their interactions. When he attempts to kiss her, well before the farewell, she pushes him away because he has just tried an incestuous, romantic kiss.

Castorf conceives of Siegfried as a complete lout. He has none of the innocence and curiosity implied by the score, and he doesn't even seem to be a youth. While he does reforge Siegmund's sword, when he finally kills Fafner, it's with a machine gun, and Fafner isn't a dragon, either. His interactions with the Forest Bird, who is on stage and quite beautifully costumed, do have some charm … until he has sex with her right before your eyes.

Götterdämmerung continues the violence of this Ring's intrapersonal relationships. Hagen tries to force himself on Gutrune, echoing Wotan's behavior toward Brünnhilde. The Rhinemaidens try to beat up Siegfried to get the ring back from him; he has sex with one of them, and so do Hagen and Gunther. Siegfried is seriously drunk in his last scene, and Hagen beats him to death with a baseball bat.

For all of the peculiarities in Castorf's staging, the production also benefits from his attention to each individual's acting, and his decisions here are mostly brilliant and deeply detailed. One need only consider how he handles some key scenes in Götterdämmerung. When Waltraute visits Brünnhilde and tries to persuade her to surrender the ring, Castorf has Waltraute try to forcibly take the ring away. When the kidnapped Brünnhilde comes to Gibichung Hall, in shock and looking half dead, she makes a regal descent down a staircase, terrifying Gutrune and perhaps planting some doubts in Gutrune's mind about marrying Siegfried. She then rounds on Gutrune and Siegfried before being pulled away from them. And Gutrune's short scene after the Funeral March, when she hears Siegfried's horse neighing, was wonderfully spooky.

The singing in this production was quite strong, although I don't know whether all of the singers would fare as well in a less supportive acoustic. Wolfgang Koch was an outstandingly expressive and intelligent Wotan. Albert Dohmen, a late addition to the cast after the tragic death of Oleg Bryjak in the Germanwings plane crash, sang well and made a brutal Alberich. Catherine Foster seemed lightweight for Brünnhilde, her cool, clear soprano best in the upper register rather than in the middle where most of the role lies, and she had surprising pitch problems off and on. The end of Siegfried marked the first time I've heard the tenor sounding better than the soprano!

Stefan Vinke was utterly tireless as Siegfried, despite some unnecessary oversinging. He could sound sweet when he backed off, and should have done that more. Johan Botha isn't much of an actor, but his Siegmund was a wonder, with beautiful tone and a crisp sense of rhythm. Anja Kampe made a touching Sieglinde, again with exceptionally beautiful tone. Claudia Mahnke's high mezzo made her a near-perfect Fricka, Waltraute, and Second Norn. Nadine Weissman's sassy Erda looked and sounded great. Stephen Milling's vocally and physically towering Hagen nearly stole the show in Götterdämmerung, as did John Dazak's scheming Loge in Das Rheingold.

The production also boasted exceptional Rhinemaidens, Norns, and Valkyries, with one or two of the latter sounding about ready to sing Brünnhilde.

Conductor Kirill Petrenko has led the production since the beginning, and I understand that he has mostly gotten excellent reviews. I was unimpressed and thought his Wagner simply not very good. Das Rheingold was oddly boneless, conducted very fast and with little attention to the structure of the piece and how the internal climaxes move it forward. Any given moment sounded good, with the orchestra beautifully balanced, but the whole never coalesced from a structural standpoint.

The exception to the rule, Die Walküre Act III, was thrilling in every way. But in the other acts and in the last two operas, his conducting was decent, but in no way outstanding. Besides lacking a structural sense, Petrenko's command of local rhythm and phrasing was lax. The beautiful chords that precede Brünnhilde's awakening at the end of Siegfried exemplify his problems. They lacked majesty and failed to bloom, largely because of Petrenko's poor handling of their timing and dynamics. The chords sounded perfunctory, and Petrenko's inability to make the music sound important marred the entire Ring. The beautiful chords that precede Brünnhilde's awakening at the end of Siegfried exemplify his problems. They lacked majesty and failed to bloom, largely because of Petrenko's poor handling of their timing and dynamics.

On the other hand, sufficient superlatives do not exist to describe Christian Thielemann's brilliance in the new Tristan production. Act II was the greatest 90 minutes of Wagner conducting that I have experienced live, between the conductor's extraordinary sense of the shape of the act and the astonishing beauty of the orchestral sound. The outer acts, inherently less beautiful than Act II, made equal musical and dramatic impact.

Thielemann's Wagner is in no way mannered or extreme; it is simply right in every way. He balanced each phrase perfectly, so that you could hear every voice in the orchestra, and yet at the same time, the instruments blended into a magnificently unified sound. He paced the work ideally, the many and complex tempo changes presenting no challenges, with each act reaching its multiple climaxes with complete inevitability, as though it could not be done any other way.

Katharina Wagner's production is extraordinarily dark, both emotionally and physically, and it's sometimes at odds with the libretto and music. Act I takes place in an Escher-like maze of stairs and platforms. Tristan and Isolde are at odds to the point that she physically attacks him. When they are ready to drink the potion, they instead join hands and pour it out, an acknowledgement of the emotional truth that they have already fallen in love, and that they are doomed, regardless of whether they drink a love potion or poison.

Act III is beautifully bleak, with Tristan, Kurwenal, the shepherd, and two attendants set in an isolated pool of light. During Tristan's long delirium, he repeatedly hallucinates Isolde's presence. She appears at several points standing or seated in a triangle on or above the stage as Tristan sings to her.

The staging of the outer acts is largely appropriate. Act II, though, despite its musical joys, is set in a torture chamber which is under observation from above by spotlight-wielding outsiders. During the duet, Tristan and Isolde hide from the spotlights, Tristan is more or less hurled into the torture chamber through a door, and Kurwenal, on stage long before his actual entrance, is beaten at least once.

Most strangely, the director portrays King Mark, the most benevolent of betrayed husbands, as an abusive torturer rather than a man deeply hurt by his beloved wife and nephew. He is clearly responsible for the Act II surveillance of the lovers, and he has Tristan tied up during the sorrowful monologue at the end of the act. And it is beyond shocking when, after Isolde sings “Mild und leise,” he drags her bodily offstage, after having stated that he's there to free her from their marriage vows and reunite the lovers.

The singing in Tristan was mostly quite good. I don't entirely understand the general enthusiasm for Evelyn Herlitzius (Isolde). She sang with inconsistent tone and frequently started pitches a third or fourth down before hooking up to them. She was not unusually vivid on stage. Stephen Gould (Tristan) has a fine tenor voice: He punched at notes occasionally in Act I but otherwise sang tirelessly, with good legato and intelligent phrasing. The greatest pure vocalism came from Georg Zeppenfeld, as Mark, who has a gorgeous basso cantante. Christa Mayer made a lovely Brangäne, especially in the long lines of her offstage solo in Act II. Iain Patterson was a sympathetic Kurwenal.

Then there was Jan Philipp Gloger's Der fliegender Hollander (The Flying Dutchman). The director is young – 34 this year – and this production, seen last in the string of performances, seems to collect every last cliché of Regietheatre shows. Instead of taking place in a village port, it takes place inside a printed circuit board that doubles as an airport, and a factory. Everyone wears 20th-century business suits or dresses, and the male choristers behave like Japanese salarymen.The Dutchman arrives pulling a wheeled suitcase. Instead of spinning wheels, the spinning chorus refers to a new design for a small electric fan. Senta and the female choristers work in the factory where it is being produced. Senta drags around a hideous statue representing the Dutchman, making her obsession with him seem more deranged than usual. Erik is a mechanic in the factory. The Dutchman's ghostly ship is never seen.

Unlike the other productions, this updating appeared arbitrary; it never meshed emotionally with the story or provided any special illumination of the characters and their behavior. It got a decent performance, led by Samuel Youn's resonant and strongly-sung Dutchman and Kwangchul Youn's vivid Daland. Ricarda Merbeth took Senta's entire ballad (“Traft ihr das Schiff”) to warm up, and none of her singing could really be termed beautiful. Her performance was extroverted and unsubtle. Christa Mayer was fine as Mary, exercising supervisory powers over the factory girls. Tomislav Mužek, singing Erik, looked and sounded rather like the young Ben Heppner, only better, because he was at absolutely no risk of cracking. Benjamin Bruns was amusing as the Steersman, or perhaps the lead salaryman, singing well and nudging the male chorus together for a group portrait taken with a cell phone. Axel Kober conducted propulsively.