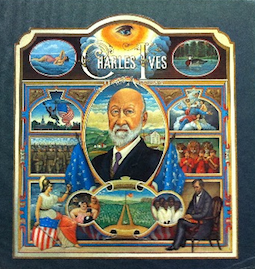

Mad Music is the provocative, but historically and musicologically correct title for Stephen Budiansky's biography of Charles Ives, to be published by ForeEdge, an imprint of University Press of New England, on April 1.

Budiansky has made significant new discoveries about the composer, finding previously unknown correspondence revealing the physical and mental impact of Ives' 1918 diagnosis with diabetes. Until now, the sharp decline in Ives' creative output at around that time was a puzzle to scholars.

Budiansky also explores and brings to life "the places, eras, events, and cultural contexts — rural New England of the 19th century, Yale of the 1890s, New York City and Wall Street of the early 20th century — that shaped Ives' development both as a visionary American composer and idealistic business pioneer."

The author adds: "Above all, what makes the story of Ives' life so compelling and of broader meaning is how he succeeded in putting into practice the transcendental ideal of a life lived for the purity of art."

A "local angle" to the book, although it's not part of it: It is to the credit of Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony to champion Ives so forcefully even in an environment without majority acceptance of the man's genius to this very day. MTT's very first subscription concerts here as SFS music director in September, 1995, paired the Beethoven Ninth with sublime Ives choral works, including "The Housatonic at Stockbridge" from Three Places in New England.

Since then, there have been numerous Ives performances, a grand Keeping Score program, and the Brant transcription of "The Alcotts" from Ives' A Concord Symphony on the orchestra's current European tour.

Even in relatively adventurous San Francisco and in the late 20th century, it was somewhat risky to present Ives on subscription concerts. As Budiansky writes, quoting David Schiff:

Much of the continued resistance to Ives in the concert halls ... was due not to the music's technical difficulties (which loom far less large to today's performers than they did in the past) not even to the chaos and incompleteness of many of his scores, but rather to the fact that his music "resists the context of the classical concert altogether," demanding that listeners be participants, and all the while really suggesting that it belongs somewhere else entirely — a town square, a revival meeting, a football game, a Victorian front parlor, a parade: It was music that challenged the very idea of the place of classical music in America.