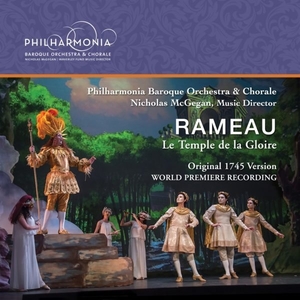

If fortune favors the bold, then Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra brought themselves months of good luck with Le temple de la gloire. Back in April 2017, Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra spread itself to stage the world premiere of the reconstructed original version of the opera-ballet by Jean Philippe Rameau and librettist Voltaire, from 1745.

At the time, having spent a large amount of money for a mid-sized organization, on sets and costumes, not to mention a troupe of Baroque-specialist dancers, the focus was on the production. A new recording captured live in the inhospitable confines of UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall on the orchestra’s own recording label, serves as a reminder that the orchestra and the top-rank vocal soloists kept the musical values at the forefront of the show.

As you might surmise, The Temple of Glory is allegorical and not deeply dramatic. Each act presents a different historical ruler trying to get into the temple. Bélus is too bloodthirsty, Bacchus too frivolous (and, of course, Envy, in the prologue, is, well … too envious). Only Trajan (who doesn’t seek entrance) gets in, amid much rejoicing. Each of the rulers has a lady love who provides whatever emotional payoff the scenes have. The best arias are for the women, and Chantal Santon-Jeffery, Gabrielle Philponet, and Camille Ortiz deliver in stunning fashion. Santon-Jeffery’s opening scene in the first act, plus her “O Muses, puissantes déesses” (O muses, powerful goddesses), and Philponet’s opening scene in the third act are obvious musical highlights of the set, where the artists touch on deep currents of feeling.

The rest of the cast is not behind hand either. Marc Labonnette’s smooth, well-projected baritone graces several roles, Artavazd Sargsyan deploys a robust tenor and a fine sense of humor as Bacchus, Philippe-Nicolas Martin is a perfectly acceptable Bélus, and Aaron Sheehan’s tenor shines in his role as Apollo and, especially, as Trajan. Everyone’s diction is exceptional, a basic requirement for this repertory.

The orchestra, stretched to 40 players (triple winds plus extra percussion and a musette [bagpipe]), captures all the rapidly shifting moods brilliantly. There are tons of short, contrasting movements, the essence of this court entertainment, and Music Director Nicholas McGegan puts the orchestra through its paces, thoroughly characterizing each one. While there’s plenty of pep in the score, McGegan is with the singers, underlining their words deftly, and keeping the scenes balanced. The chorus sounds as superb as ever and David v.R. Bowles’s production and engineering is spacious, allowing this large work to sound full but not boomy, and with less loss of clarity than a listener in the actual theater would have experienced.

A la mar — Los Cenzontles and Shira Kammen

Subtitled “Reconnecting Early European and Mexican Roots,” this album brings together the Bay Area band and cultural arts center with indefatigable early music string player Shira Kammen. Los Cenzontles founder Eugene Rodriguez, who studied with S.F. Conservatory guitarist David Tanenbaum, conceived of the project, which fits well with a number of recent releases in early music connecting traditional folk music to Baroque and earlier classical traditions.

Kammen sounds completely at home on tracks like “El Siquisirí,” an original duo by Rodriguez based on a traditional theme, and even more on tracks where the band is in full cry and she is playing an obligato line. Perhaps most striking is the dirgelike “El Zacamandú,” in which Kammen plays vielle against the voices of Lucina Rodriguez and Fabiola Trujillo over a drone bass. Some of the son jarocho numbers seem to gain depth in this context as well. The recording itself, produced by David Luke and Emiliano Rodriguez, and mixed by Greg Morgenstein, is professionally done and released directly by Los Cenzontles.

The Magnifick Consort of Four Parts — Wildcat Viols

Released a year ago, this is a recording about the group as much as the repertory. Formed in 2003, Wildcat Viols has been one of the U.S.’s finest viol consorts, though life has scattered its players (Joanna Blendulf, treble; Julie Jeffrey, tenor; Annalisa Pappano, tenor; Elisabeth Reed, bass) to various places. When they come together, the sound they make on these instruments, so ubiquitous in the 17th century, is not just incredibly powerful, it’s beautifully blended, truly concerted, like the best chamber music.

The centerpieces on the album are nine fantasias by Henry Purcell (from 1680), probably the most famous pieces in the viol repertory. They have been recorded many times by great musicians. But Wildcat has a claim on your attention in these works, because they perform them beautifully. The group have also interspersed the fantasias with two suites by Purcell’s teacher, Matthew Locke, from a collection of six called The Consort of Four Parts. (The title of the album comes from a reviewer’s compliment from Locke’s time.) Wildcat Viols also squeeze in two short sonatas by Giovanni Legrenzi. The CD is professionally done and released directly by the group, and available for download or purchase at CDBaby online.

If Wildcat Viols performances are likely to be in short supply in the next few years, this will be a welcome reminder of their top-flight musicmaking, and of the extraordinary sound of the underrated viol.