Rudolf Nureyev’s career was as extraordinary as the fact that many people no longer know about it. That will likely be remedied with the de Young Museum’s new exhibit, “Rudolf Nureyev: A Life in Dance,” which opened on Saturday, displaying 80 costumes from France, primarily doublets and tutus by famous designers, that he and his partners wore, along with performance photos.

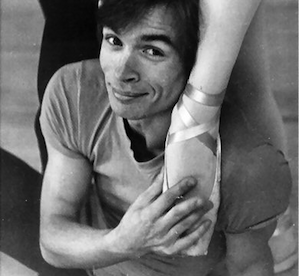

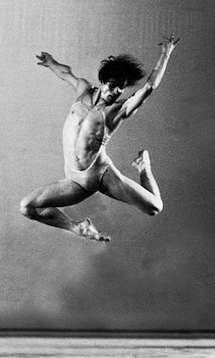

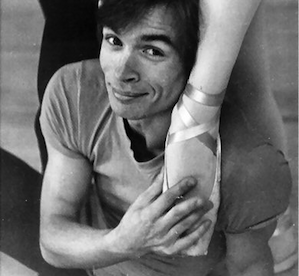

Nureyev, who leapt into view in 1961, was the first dance superstar. His fan base created the phenomenon known as Rudimania. And he had a will, or some might say a whim, of iron.

He was a dancer both gifted and driven. He danced stunningly, then competently, and finally relentlessly, well beyond the moment when he should have stopped. He professed indifference to the critics who said the world’s greatest dancer was in the process of taking it all back. “I don’t want anybody, anytime, to tell me I should go away,” he told me once. “It’s not their life. I don’t tell them to go back to Harvard to study English.”

He was a famously mercurial dance director with a detailed knowledge of the great classical ballets from Imperial Russia. He brought them to the Paris Opera Ballet, where he was artistic director from 1983 to 1989, beginning with La bayadère, which, like other works he staged, was reproduced in other classical companies around the world. He revitalized the career of Royal Ballet prima ballerina assoluta Margot Fonteyn, twice his age, whose stardom, in exchange, helped bring him international prominence. They shared an artistic and personal (how personal, nobody seems to know) partnership that lasted 17 years.

Dressed to Stun

The de Young show, sponsored by the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation, is a reminder of a superstar’s magnificent obsession with exquisite textiles and designs, as much as with the infinite details of the ballets that framed them. The show was curated by Delphine Pinasa, director of the Centre national du costume de scène (CNCS) in Moulin, some 190 miles south of Paris.

The museum, founded in 2006, holds the objects remaining from Nureyev’s estate. The CNCS also contains the costumes and scenery from France’s venerable national theaters, including the Opèra de Paris and the Comédie-Française. This, the de Young’s first costume stage exhibit, will be the only presentation in the U.S. Under the direction of Jill d’Alessandro, curator of costumes and textile arts, it pays tribute to the late Nancy Baer, the de Young’s former costume collection curator. It continues into next year, the 20th anniversary of Nureyev’s death at age 54 from AIDS.

It’s almost impossible to think of Nureyev’s costumes without his animating presence inside them, but let’s try. Nureyev wanted his costumes to be as thin as possible, said curator Pinasa, “to emphasize his body.” Her favorite of the collection is his black and white costume for the 1974 production of La bayadère, designed by Martin Kamer. Nureyev’s doublets, according to the catalog, all had a similar cut to allow free movement of the head, neck, torso, and arms, without gaping during lifts.

Onto these were applied decorations such as embroidery and jewels, vertically on the front, at midsleeve, and on the wrists. Designs by Franca Squarciapino (for Swan Lake), Nicholas Georgiadis (Raymonda), Hanae Mori (Cinderella), Cecil Beaton (Marguerite and Armand), and Toer Van Schayk (Le Spectre de la rose), among others, exemplify the range of Nureyev’s repertoire.

In 2010, de Young Museum trustees Bernard Osher and John Buchanan saw the exhibit in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and wanted to bring it to San Francisco, which just shows how the world has changed since the day 51 years ago that Nureyev, only 23, defected from the Kirov Ballet of Leningrad, the Soviet Union, where he was a rising star.

A Dramatic Escape

The company was on tour, dancing in Paris. Nureyev spent his evenings hanging out with Paris Opera Ballet dancers and their friends, leaving his hotel alone, in defiance of rules requiring the dancers to be escorted by minders associated with the KGB. They decided to take him away from the tour. With his company at the airport as they waited to fly to London, Nureyev learned that he was about to be flown to Moscow, instead. The pretext was that he was to dance in a special show for Nikita Khrushchev. And he knew that he probably would never be allowed out of the Soviet Union again.

“Rudolf didn’t need courage. He had so much courage that it wasn’t even courage anymore.” – Mikhail Baryshnikov

His revised flight was short but momentous. With the help of a French friend, Nureyev crossed to the other side of a bar in le Bourget airport and told the French police who had been summoned there, “I want to stay in France.” The police firmly rebuffed the attempts of his KGB minders to yank him back, saying, “You are in France!” Nureyev’s was le Bourget’s most famous landing since Charles Lindbergh’s.

Nureyev was the first of the dancing defectors, leaving before Natalia Makarova, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Alexander Godunov. He had no road map to speak of. Baryshnikov, quoted in Diane Solway’s magisterial biography Nureyev: His Life, summed it up neatly: “Rudolf didn’t need courage. He had so much courage that it wasn’t even courage anymore … it was like a bird in a cage, and suddenly the door is open.”

Once in flight, he began exploring nonclassical tradition, devouring movement of all kinds, but especially American modern dance; he danced with Murray Louis, with Martha Graham, with Paul Taylor. But first there were the classics.

I initially saw him in Washington, D.C., in 1963, dancing with Fonteyn. Even from the balcony, his face was unmistakable, and the dynamism promised by the black-and-white evening news clips was all there, and even better. In excerpts from Swan Lake, Nureyev flew, landing his leaps as if on a plush carpet. I cannot remember what he wore. Fonteyn, twice his age, all in white, contrasted, with her exquisite calm and perfect placement. It was a decade before the ballet boom, but this was like seeing the Beatles. The crowd went wild.

Living Large: The Grand Style

Fittingly, for one of the greatest dancers the world has ever known, Nureyev never stopped moving. He had homes all over the place: in Manhattan, in the Virginia hunt country, on the Quai Voltaire in Paris, in Italy (where he owned three little islands), on St. Bart’s in the Caribbean. To those homes he often brought friends or family; his relationships were legion, platonic or not. But he was singular and single and often alone. “In the end, you marry yourself,” he told me.

It was a decade before the ballet boom, but this was like seeing the Beatles.

Nureyev’s private aesthetic tilted toward the baronial. His Manhattan apartment in The Dakota on Central Park West had a dining room roughly the length of a football field, with a huge table covered with tapestry; the floors and walls held priceless carpets. He had a well-known collection of paintings of male nudes. He had statues and busts and photographs and Warhols. He collected damasks and cashmere. After his death, most of his estate was sold off after a series of nasty lawsuits, brought by some family members and close companions, were settled. What remains, though, will have a special exhibit space at the Moulin museum.

Nureyev liked velvet and slippers and soft suede boots. At the end of his career, dancing on Long Island, he once snuck to the doorway of the theater, in his lush velvet Moor’s Pavane costume, to see whether a critic whom he’d newly anointed his sworn enemy was in the house. He wore hats like no one else; a dark-green velvet beret was long a trademark. At Lincoln Center between rehearsals, he wore a white tennis cap as a disguise. With cheekbones like that, he didn’t have a prayer. Frankly, Nureyev could have walked across the plaza with a sack on his head and he still would have been unmistakable. I asked him about his charisma. He paused, wrinkled his eyebrows, considered, and finally spoke. “You exude …,” he chuckled, “essence!”

“You exude … essence!” – Nureyev, on his own charisma

He could be mod or modish; he was part of the ’60s swinging London. He ran with Jaggers Mick and Bianca, Kennedys Jackie and Ethel. He and Fonteyn hung out on their tours: In San Francisco in the ’70s, they partied in rich-hippie garb, and even spent a night in the police station after being caught in a raid on a pot party. But Nureyev grew up in wartime poverty, and there was that strain in him: He mended and mended again his costume from Le corsaire, ragged and patched blue breeches that will be in the de Young show, and his ballet slippers usually looked as if they’d been through a wringer.

A Star’s Demands

He was beyond fussy about his costumes and those of the ballerinas who danced with and for him. He was interested in historical detail as well as nuances of ornamentation. And he remained insistent about who was the center of attention — as if anyone watching him would have a moment’s confusion. For a Swan Lake at the Cour Carrée in the Louvre in 1973, he decided that his black jacket for Act 2 (the ball, with the treacherous Odile) wasn’t fancy enough, and wore one from another production. But he decreed that the black-and-gold tutu of his partner, Paris Opera ballerina Ghislaine Thesmar, was too fancy. “Christmas tree!” he sniped, and the ballet directors backed him up. (I happened to catch that show, and you couldn’t take your eyes off him.)

Nureyev totally revised the Paris Opera Ballet’s tutus, which he thought were too short and overemphasized the derriere. He made them longer and wider, and added two more layers of fabric to the skirts. The tutus crossed the Channel and were adopted by Dame Margot’s company, so the Royal Ballet’s “British tutu,” Pinasa said, is really French. As is this exhibit, she noted. Nureyev “always came back to France. He had a strong link with this country, and the work he did with the Paris Opera Ballet changed the quality of the company.”

It’s not a part of the de Young show, yet the ballet that best illustrates its theme has to be Vaslav Nijinsky’s Afternoon of a Faun. The Faun seizes the gossamer scarf dropped by the Nymph who has fled his attentions, caresses it, lies on it, makes love to it. It created a scandal at its Paris premiere in 1912. Watch Nureyev perform it on YouTube: Dancer, dance, object, beauty, sensuality — all are one.

So this exhibit, like Nureyev, transcends the narrative of a life cut short. His tombstone, at Saint-Genevieve-des-Bois cemetery near Paris, was created by Ezio Frigerio, who designed Nureyev’s final production of La bayadère for the Paris Opera Ballet. It’s a mosaic rendition of an oriental carpet, its folds draped over a traveler’s trunk.