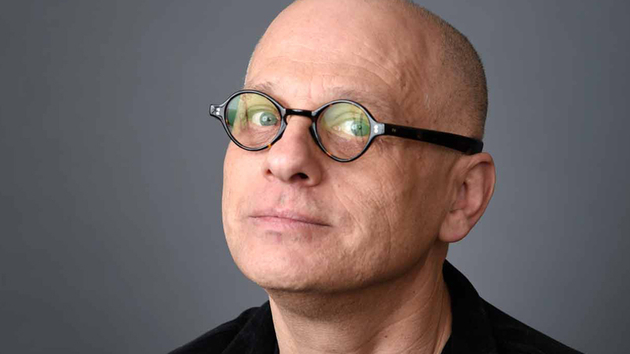

For 12 hours during a marathon performance ultimately aimed at building bridges between classical and new music in 1987, composer David Lang and other musicians earned swift and appreciative acclaim for what he called “banging on a can.” As fans of innovations in sound know, the energetic music collective Lang co-founded with Michael Gordon and Julia Wolfe is today the performing arts organization Bang on a Can. Its growth has led to recordings, commissions for emerging composers, a summer festival to develop experimental composers, multi-disciplinary residencies and partnerships, “All-Star” tours, and more.

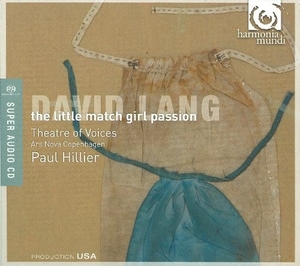

Lang has independently enjoyed accolades: notably winning a 2008 Pulitzer Prize and a 2010 Grammy Award for the little match girl passion. In 2016, Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations arrived for simple song #3, part of Lang’s score for Paolo Sorrentino’s film Youth. His works are performed all over , and used in films and by ballet and modern dance companies. He has been on the faculty at the Yale School of Music since 2008.

But in an interview two weeks prior to the world premiere of teach your children, a new choral work commissioned by the San Francisco Choral Society, Lang says building bridges continues to be a slog. In an era of arts spending cuts and noticeably less music journalism, bridge-building demands diplomacy, even tiptoeing.

“Now, with all the criticism and cuts to music and negative conversations, I feel bad offering criticism about any aspect of the arts, especially mainstream journalism, which is getting reduced and reimagined. Hopefully, not-for-profit places—or independent music news sites like SFCV — will take up the slack. It’s a luxury I had ten years ago — to criticize how music is talked about in the press. Now, I feel a little guilty because there’s so much less music being talked about in the press.”

Lang says there is audience enthusiasm for connecting classical music to new genres and art forms, but institutions are slow to adapt. A New York Times Opinionator blog Lang wrote in 2011, “A Pitch for New Music,” he says remains applicable. In the essay, Lang compares baseball and classical music and ponders why loving, respecting, and “talking about it in a holy way” enhances the enjoyment of a baseball game, but when reverence for classical music traditions coexists with listening to new music, listeners’ enjoyment is restricted. “Outside, it’s more open, but institutional things like schools, music criticism, or scholarship, that’s where (acceptance of new music) is not changing.” He mourns the intrusion of good/bad judgement in reviews and recalls as a student at Stanford reading in The Village Voice Tom Johnson’s coverage of the Minimalist music scene. “He’d go to a cool concert and tell you why it was cool. His job was to report on the vitality of the new scene, not why this part was good or that part was bad. That’s it. I miss that.”

With increased visibility as a composer of new music, Lang says it’s not uncommon for people to call him and say, “Do something weird for us.” Of course, what he hopes for are callers who tell him they love and respect his work so much he can do whatever he wants. “No one in their right mind would do that! They have obligations and ask me to do something based on what their needs are. My job is to get someone excited to do something different than what they asked. But it is true that now, when I answer with something preposterous I want to do, people are more comfortable thinking I might know what I’m talking about.”

Even so, he says, “It’s easy in a career to do something people like and think ‘Ok, great, I never have to do anything else and everyone will be happy.’ But you won’t be happy. So it’s amazing that I’m allowed to ask myself how I can satisfy my own curiosity and make everyone else happy too.”

Counterintuitively, what makes Lang happy is tackling something that makes him extremely uncomfortable. He positions himself behind a topic he’s unsure of, conflicted about, or avoiding, then drives full force into the vortex. “If I’m avoiding, I get curious. That happened with the little match girl passion. I spent 50 years of my life wondering how I could fit into a world of singing, appreciating, and loving music worshipping Jesus when I’m not a Christian. I always thought I wasn’t going there: What is the value of Christian music for people who are not Christian? I decided I’d open up the wound and put my finger in it to figure out what the wound really does. That became the match girl opera.”

In the case of teach, the new work written for the Choral Society, Lang says Artistic Director Robert Geary phoned and offered a commission for “a big piece” with a children’s choir. “I got excited because I’m a parent and have three grown children. I sometimes feel I wasn’t as good a parent as I wanted to be. They learned all my worst habits. I messed my children up! I’m constantly thinking, ‘How could I get a message to them? How could I have protected them from my worst habits?’”

Lang consumes “tons of news” and wastes “lots of time” on Twitter and social media sites daily. While thinking about the new work and the Piedmont East Bay Children’s Choir, he realized, “All I heard online were stories of exemplary children: either those who were really good, like activism from Parkland shooting students, or people who were really bad, like kids wearing ‘Make America Great Again’ hats and doing terrible things.

“We were talking about them as if they’re discreet units. But all of those children were raised in an environment that either encouraged or discouraged them to be good or to have other values. What were those messages they were getting? Everybody wants to pass on what’s important to their child. Regardless if we agree on the things, we all agree, universally, that we want to pass on lessons.”

In search of universal-type answers, Geary says Lang used the auto-complete function of online search engines to create a catalogue of lessons we should teach and lessons children learn. Prompts included “we must teach our children to…” and “the truth is, we all…“ and “when I was young, I learned to….”

The libretto for the first movement sets the lessons taught — to swim, be good with money, be good listeners, and so on — to text. Lang deleted any product-centered, pornographic, hateful, or person-specific replies. The second movement is based on an actual lesson structure Lang found in a second-century Hebrew text. “It’s by a Jewish author, Ben Zoma,” he says. “It basically asks ‘who is wise, rich, strong, deserving of honor?’ A wise person listens, a person satisfied with what they have is rich, a person who gives honor to everyone is deserving of honor. “It seemed like a beautiful statement of what we all need,” concludes Lang. “A solo soprano [Marnie Breckenridge] gives the lesson to the children’s choir. They respond and ask questions. They’re hungry for knowledge.”

The final movement features heavy, serious answers Lang received when the search began asking the secrets/answers we hold off from our children. “We will never be able to end climate change with hopes and dreams” and “we all die” are examples. To prepare children to deal with these heavy things, Lang says, is the job of parents and adults.

Geary worked previously with Lang on battle hymns, which received its West Coast premiere by SF-based Volti, the Choral Society, and the Piedmont East Bay Children’s Choir at Kezar Pavilion in 2013. Although noting similarities — homophonic text settings, brief statements followed by moments of silence, triadic- and modal-based harmonies — hymns was unaccompanied and teach is scored for orchestra. Traditional classical harmonies are not an element in the new work. Geary says, “[Lang] invites the listener to live in the musical suspension of time, which allows reflection on the meaning of the text. He’s not telling us a story with a conclusion, he’s inviting us to be part of the story.” Because the Choral Society often performs classical repertoire, the more modern approach is refreshing. “Singing harmonies that are not simple or that don’t follow the predictable patterns of history requires an open-mindedness and a willingness to practice the unknown,” he says.

Which leads to final questions for Lang. What is left to explore? Which sounds and whose stories are of proximate interest? Lang says he’s dealing interactively with theatrical work that questions what it means to be a citizen: What is our obligation to each other? How is society organized to either bring us together or push us apart? How can we stand up against the things that push us apart?

“I look at fractures in society and think about the issues. I make pieces that don’t hit you over the head but allow me to think (in this case) about what we owe to our fellow citizens.”

Composers — Lang among them — can never be sure a new piece will have lasting value. But he knows the feature he recognizes in music with lasting value. “Work that’s worthy of hearing more than once is work that doesn’t resolve itself. A work that ends with all the ribbons tied up neatly may be successful, but it’s one you don’t need to hear again. Traditional opera, I love, but it invents a problem; then the problem gets solved. Tosca, everyone becomes evil. At the end, everyone is dead. Problem solved. That’s satisfying, but my life doesn’t solve problems that way. My problems are solved temporarily, if solved at all.” Composing, in the end, is a lot like parenting.