A phone interview with cellist Jonah Kim is a boisterous, animating experience. While revered for his technical skills and energetic and sensitive performances of new and traditional works in the classical canon, he confesses a “hidden secret”: having fun is central to his artistry. His is an artistic practice built on hard work and enhanced through friendships and long-term relationships.

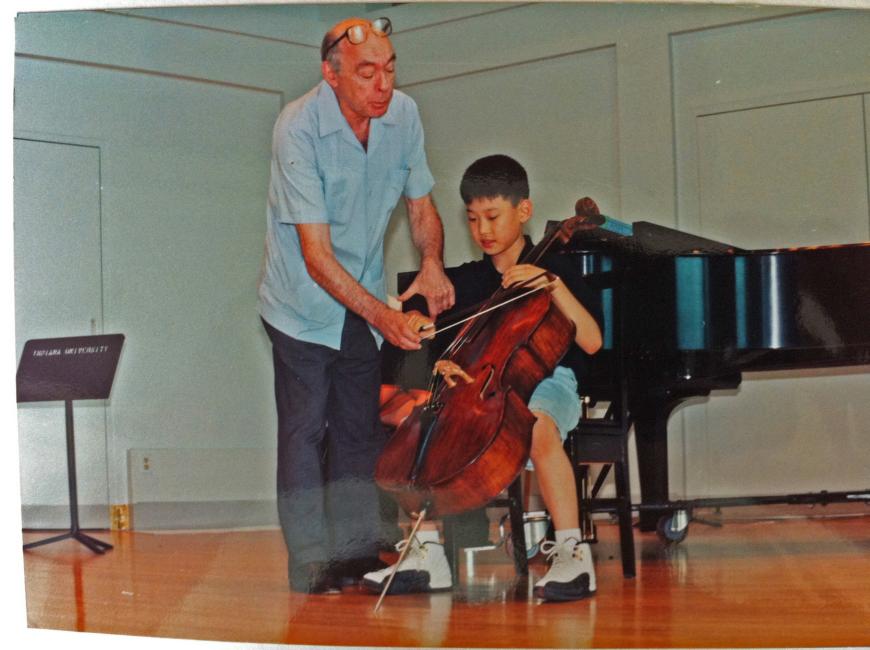

Kim was born in Seoul, South Korea, and in part taught himself to play the cello while watching VHS tapes of Pablo Casals. His family arrived in the U.S. when he was 7, and his father, a pastor at a Korean Presbyterian church in New York, introduced him to the cello. He was awarded a full scholarship to The Juilliard School’s Pre-College Division the same year. Kim’s friendship with János Starker began in correspondences, and the famed cellist later invited him to Bloomington, Indiana, just before Kim’s 9th birthday. He studied with Starker throughout his career at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he enrolled at age 11.

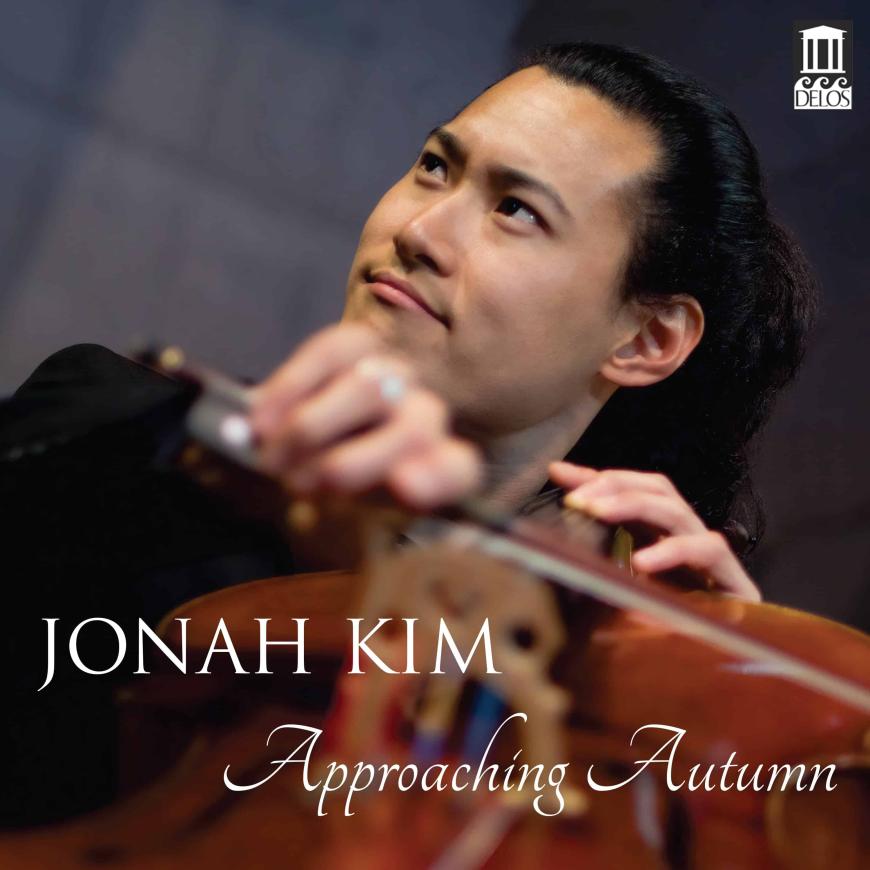

Kim made his solo debut with Wolfgang Sawallisch and The Philadelphia Orchestra at 12 and has since found a particular passion for chamber music. Frequent collaborators include conductor/violinist Scott Yoo, who hosts the hit PBS series Now Hear This; pianist Jon Nakamatsu; violinist Chee-Yun Kim; and members of ensembles such as the Orpheus and New Century Chamber Orchestras and the Guarneri and Tokyo Quartets. Kim’s new ensemble, Trio Barclay, with pianist Sean Kennard and Pacific Symphony concertmaster Dennis Kim, is in residence at Irvine Barclay Theatre in Orange County, California. And with pianist Robert Koenig, Kim has a new album out, Approaching Autumn, which bookends Mark Abel’s compelling title work with Zoltan Kodály’s and Edvard Grieg’s cello sonatas.

We spoke at length about his life during recent times and about the intricacies of his new album.

Because during the pandemic you’ve been doing projects with Julia [Rowe], let’s start with how you met your wife. [Rowe is a soloist with the San Francisco Ballet.]

Our origin story is funny. … We met at my house. I used to throw weekly parties when I moved to San Francisco. I had friends who put me in a house with other artists and ballerinas. We had parties on Sunday night because no one had shows on Sunday nights. We had afternoon matinees and then we’d relax. We cooked good food and arranged some chamber music. My [then-] roommate Diego dances for the ballet, but he also runs a side business and makes paella. So we had little chamber salons. We were kids and also wanted to have fun. We’d read music on this side of the house, and on the other side, they’d have PlayStation going, karaoke boxes. It was the party house. Julia, who wasn’t my wife at the time — she started out in the [SF Ballet] corps for a year and was promoted to soloist — started coming to the house. One week she came when we had a Caribbean theme. I expected coconut water or dessert, and she brought a bunch of real coconuts. I looked at her and thought, “This woman is very interesting.” She asked me if I had a way to open them. Luckily, I had an old machete and said, “I have just the thing.” It was hanging on my wall, and I took it down and we chopped it up and we had real coconut water. That’s how we met, but she was dating somebody else at the time.

A few years ago she came to another party. I had moved and was living alone but continued to throw these parties. We had both just gotten out of relationships, and we started hanging out a lot. We got married right at the beginning of COVID. We had set a date for the end of May, and we had booked everything. We had to delay. Then we kept delaying. A week, a month, then it became six months. So we did it on Zoom in November 2020, online. [The couple ran 300-foot internet cables and livestreamed it in the redwoods somewhere.]

What occupied most of your time during the two years of lockdown when there were limited in-person performances — other than the work on this new album?

Many things started to click for me because we took time to process. Everybody else started their channels, but we took time off because we had been posting things pretty regularly. We took a minute to think about if what we were doing was important, or necessary, or even wanted at all. This is a big thing between me and my wife since all of this began: We keep asking each other, “Are we busy doing a thing right now, or are we actually accomplishing the object of the thing right now?”

Getting our art [to have] meaning was the first step. We said let’s not create anything meaningless. Let’s think about why we’re doing what we’re doing. My thing was that we couldn’t help people who were being hospitalized. We’re not making their lives better in any way. But then, friends came to me and my wife and said they really missed the art. Especially when we’re in homes, hospital rooms, and beds, trying to survive, they said we need art more than ever. My wife and I looked at each other and said maybe there is meaning here. We started taking requests from friends. We made do with what we could. We went on our driveway and made a dance/music video. Our equipment was terrible. We started with iPhones, then upgraded to handicams, then a little Sony video camera. Eventually, our friends upgraded our entire system, and now we have Sony α7 cameras. … We’re able to take the art we were trained to perform and bring it to people in a way they can consume on their phones, laptops, and iPads.

What is most important to your cello playing that has nothing directly to do with the techniques and artistry of playing the cello?

It’s people. The most important thing is the conversation, the story. If that’s not there, it’s meaningless. So much can happen just by drawing a line between even the two simplest dots. Music is the simplest and most direct expression of that. Julia agrees that without that initial attitude adjustment, it’s hard to dance without music.

What defines the preparation time or the approach you engaged in with your pianist Robert Koenig?

Bob and I have known each other for almost 30 years. We didn’t work together until five or 10 years ago. He now has a school in Santa Barbara, and I know his way of working is compatible with mine. We trained in the same places and worked with all of the same people. We had played together several times over the years, and I knew the trust was there. The rapport we have in the studio: I knew he was one of the best and strongest of musicians and with that strength came flexibility. The major rehearsing started in January 2021. He flew up a few times before that so we could read through it together and then do the work at home. We rehearsed in person; he would fly up.

Describe those rehearsals.

We had an idea of how we always wanted to sound together. We went for that from the very beginning. I told him my goals. I wanted to establish a few bullet points that hadn’t been established with cello playing. We’re really starting to push the level with our technique and our musicality, with both hand in hand. We’re playing more rhythmically and more in tune. He helped to keep me on that path. His artistry — he’s such a poet without having to take time. We come from this old school tradition that taught us time is the last thing you want to alter in order to get the expression you want. Do it with color, do it with anything else, before you mess with the time. Cello music is usually not played this way; it’s usually played so freely.

Let’s unpack the perils and possibilities in Abel’s Approaching Autumn that led you to select the work at this time.

Many, many perils. This piece is like Mark looked up every difficult cello piece and made a list of all the most challenging things. It’s like he wrote all of them into his piece. There are so many perfect fourths and sometimes parallel fourths — and that’s not easy to do on a cello. … Mark built it into his piece. Just to play it like a computer can play it, is difficult to do. Yet, it is so much fun. And there’s nothing that doesn’t jibe with the general palette we hear in the world right now. It tells a compelling story, and the rhythmic variations throughout, if the executor can manage the long lines within — the rhythms develop and make a beautiful story.

The storytelling in Approaching Autumn, the melodic fragments laid down and not revisited, the shifting moods — are these the markers of contemporary classical music? And are there other progressive markers?

It’s a style thing, the kind of story Mark chose to tell in this piece. There are other pieces, even by Mark, that don’t do that. In general, pieces are getting shorter, yes. And the segments are getting shorter. I wouldn’t say that the segments of Mark’s piece create movements per se, because they’re very gradual. They tell a story.

With the Kodály, what was most important to achieve?

Mentally, to get past the way it’s always played. I grew up revering Mr. Starker’s recording. Having studied it with him and having a firsthand account on what he felt about it — he wanted to play it as perfectly as he could. Exactly the way it is written, like a machine. At that time, that’s as close as anybody got. Nobody else got even remotely close to what he could do. It’s hard to play it consistently in one tempo. As soon as notes gets faster, it feels more difficult. Our human tendency is to go even faster. When something gets louder, we want to get faster. When gets something gets slower, we want to get softer. In fact, we need to do the opposite for the sake of the listener.

The sonata by Grieg and performing the work with Koenig: Does he bring out certain qualities in your work that other pianists do not?

He’s a doctor: Dr. Koenig. He’s like the leading collaborative pianist in the world. He has a sense of class and quality. There’s certain things he just won’t do. He said to me, “I know you’ve played with so-and-so. They can play everything really fast, they can play every note twice if you want them to, but I just can’t play that way.” We chose tempos that were good for us, pacings good for us. He brings quality. … He’s playing 90 percent of the notes. To play with a pianist or a symphony or a string quartet, you have to have everybody on your team. You can try to overcompensate, but that will make it worse. It won’t get you the expression you are going for.

I want to dive into the challenges of this work, especially in terms of the range it requires, the importance of transitions within each movement, and also the arc or balance between movements that form the whole.

Usually the Grieg is played like a celebrity DJ, kind of tossed off, like a circus thing. Like it’s a joke. It’s unfortunate because I consider it one of the great Romantic sonatas. It’s the one sonata where you get a cadenza and a sonata, so it’s almost like a concerto. It tells a beautiful story. Because it feels ethnic or folky or might feel predictable, people look down on it. That’s missing the whole point of art in general. We’re supposed to be celebrating that very aspect: the culture.

What work or kind of works would you want to record next?

I’m interested in all music. Every note, I fall more and more in love. My new trio has commissioned three new works for our next concert. We recorded Mark’s new piano trio. He pumped it out in a couple months. My friends give me great works to play, people we’ve commissioned. I have so much new music on my desk, I could swim through it. ... I want to do a balance of both [new and classical works]. I think it’s important that we respect tradition and learn everyone we can. I think it’s also important that we try new things.

Are there works in the classical canon — or new things — that you don’t yet feel prepared to play?

If I were a pianist and [had] that much music, I would be able to answer differently. There are only so many works [written] for cello. We are learning a lot of new music to push the boundaries. I’d like to do something like Rostropovich did where he doubled the size of our repertoire. I would love to have more people write cello music, use all the qualities of cello without missing anything. We can play cello now. It’s not like it was 50 or 100 years ago. It’s always been behind, technically. Getting around it is harder to do with precision. But we can do it. Technically, kids today play circles around [cellists] of the past. Right now, there’s probably someone who can play better than I can, and probably [someone] 3 years old!