Establishing Telegraph Quartet in 2013, violinists Eric Chin and Joseph Maile, violist Pei-Ling Lin, and cellist Jeremiah Shaw launched a hybrid. Displaying impressive not-just-this-but-that command of both standard classical chamber music and contemporary classical repertory, the quartet earned the 2016 Walter W. Naumburg Chamber Music Awards, a grand prize at the 2014 Fischoff Chamber Music Competition, and performances at Carnegie Hall and Herbst Theatre, among other venues.

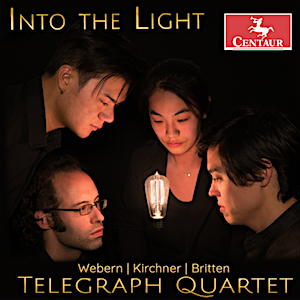

At festivals, outreach programs, and in collaborations, the foursome champion 20th- and 21st-century work; commissioning or performing centuries-spanning repertory including works by Schoenberg, Webern, Britten, Robert Sirota, John Harbison, and more. Their debut album, Into the Light (2018), features three short string quartets by Webern, Britten, and Leon Kirchner, and has been received with critical acclaim. In addition to tours and performances, members of the quartet are instructors at San Francisco Conservatory of Music and conduct lessons in private studios.

At festivals, outreach programs, and in collaborations, the foursome champion 20th- and 21st-century work; commissioning or performing centuries-spanning repertory including works by Schoenberg, Webern, Britten, Robert Sirota, John Harbison, and more. Their debut album, Into the Light (2018), features three short string quartets by Webern, Britten, and Leon Kirchner, and has been received with critical acclaim. In addition to tours and performances, members of the quartet are instructors at San Francisco Conservatory of Music and conduct lessons in private studios.

As if the flurry of private lives, administrative duties they share to keep the quartet in motion, performances, and tours aren’t enough, innate curiosity and never-enough attitudes have the quartet entering unexplored territory once again. “Songs of Love and War, Peace and Exile” is a collaboration showcasing cabaret songs with German composer/vocalist Theo Bleckmann and pianist/composer Dan Tepfer. The performance Jan. 25 is part of SF Performances’ experimental series titled “PIVOT: String Theory.” The PIVOT concert series is now in its fifth year.

In an interview, Eric Chin spoke about the upcoming performance masterminded by Bleckmann, the quartet’s debut appearance at Lincoln Center on Feb. 6, and about Telegraph’s work now and in the future.

What’s exciting and what’s intimidating about appearing with Theo Bleckmann?

The most exciting thing is that he clearly has something fascinating to say. The thing that’s scary is that we don’t know him at all. It’s a new thing. When you jump together and put on a performance, you have to get immediately personal with people you don’t know.

What is Dan Tepfer’s role in the performances?

That’s a good question. The conception of the show is from Theo. We have a huge list of rep but haven’t worked together yet. We actually won’t all be together until January 22nd. We have three days. It’s not a lot, but having even that much time, sometimes is a luxury.

The Berlin cabaret songs: Do they allow Telegraph to demonstrate something new or less common?

We’ve been doing more collaborations with vocalists because of the repertoire we’ve been playing. It’s always interesting to work with vocalists because it’s what we’re trying to do on our instruments. How can we “sing” a line on our instruments?

Good question, how can you rehearse to achieve that quality?

Sometimes we literally sing a line in rehearsals to see how it feels in the body. Intonation is automatically forgiven when we sing, because we’re not good singers, so we latch onto phrasing and character. We can see the rhythm of a phrase in the body because the instrument isn’t in the way. We’re typically so meticulous with our playing that a missed note or rhythm can mean we miss the natural intentions.

Sonic balance is one of the quartet’s distinguishing features. What are the practices, tools, or philosophies you use in rehearsals to achieve and maintain it?

The sonic balance, the different voices, we never think we’re quite balanced right. So we’re always tackling it. We keep hitting from different angles. We change our sound timbre on each instrument so all the voices can come through without being on the same plane.

Can you provide an example of not being on the same plane?

If I’m going for a crimson red, let’s say, I play a faster vibrato and deeper in the strings. If someone else is going for blue, that’s a closer-to-the-bridge tone, maybe not so much vibrato. We don’t specifically say the color “orange,” of course! We leave words behind and refer in general to playing with different colors. It’s less about matching color to color than about complimenting each other.

The four of you have strong, individual voices that combine to create cohesiveness. How is unity reached while not damping your individual strengths?

We all have, inherently, a natural stubbornness. We fight for what we want. We say, “I think this note is as important as that note.” It takes more time to figure it out, and if we were always more agreeable, it would be more efficient. But there’s more personal investment and commitment our way. Spending the time means we’re really inside the music and it’s meaningful to us.

Personally, I think if we’re going to do it, we might as well be in it. There’s nothing more tough than the lifestyle of musician, and also nothing more rewarding. Unless you’re invested in it, I don’t see a point in doing it as a profession.

In performance, listening and responding to others in the quartet is vital. When you’re playing a 19th-century classical work versus playing a contemporary piece that might be scored with improvisational elements, is the listening different?

The listening is quite different, actually, for classical versus more contemporary work. We work hard to learn from both. The classical, the masterworks, even though we have a strong understanding, can be difficult to rehearse because there’s more conditioning, more habit — and stronger opinions based on that. It’s harder with those pieces to know if we’re being open to new things. To really listen is harder.

And it’s possible with tonality, like with Beethoven, it’s easier to take for granted an unusual-for-the-time half-step. The idea of dissonances, to the degree that they affect us now, we take for granted. But in Beethoven’s time, that half-step caused riots. Music now is more emotionally raw, the dissonance expected, so we hardly even hear it. And it no longer makes people want to get up and leave. I wonder what would make people get up and leave during our playing of Beethoven now?

If your approaches mesh well in practice or with particular repertory, what steps do you take to avoid complacency?

We bring in outside help: our colleagues at the conservatory, if they have time. That outside ear is so helpful. Within the group, we can sometimes take one person out (and play a work), but that changes the tone. It’s a tradeoff. If we can find someone from the outside who we trust with letting us know how sound is traveling and communicating, that’s best. Actually, if you can play for anybody — because the audience is mostly just people, after all — it’s good to get a layman’s take also.

Are there contemporary composers whose work fits most comfortably in the quartet?

For some reason, the Second Viennese School, [Arnold] Schoenberg, [Alban] Berg, [Anton] Webern and others. Somehow the struggle of the music seems to match what we look for. The era also takes a lot from old masters and tries to evolve into the future. There’s a very strong bridge; taking old ideas of structures and tonality and pushing past it, shattering the limits, and creating a new language.

Schoenberg tried to encompass everything that had happened before him and pushed, eventually coming up with the 12-tone system. It’s not necessarily that we’re more excited by this music than we are by Beethoven or Haydn, but what we’re communicating comes with more ease. We have the same emotion and commitment to anything — good music is good music — but we like the harder nuts to crack. Why? Because people have an opportunity with Webern or Berg, to “get it.” We hear from people all the time that they never liked this or that composer, but now they do. We’ve opened a door for someone. It’s quietly rewarding.

The living composers are important to us as well. Bob Sirota and John Harbison are composers we’ve commissioned because their work is personal. Their passions come across strongly. Bob’s exploration of his internal feelings is inspiring. John, I love his sense for harmony and his love for the past. He’s a Bach fanatic and a great jazz musician. He has incredible links to different genres and different music.

What, to you or to the quartet, distinguishes a successful collaboration? Does it always culminate in a great concert? Does it ever come in a failed, but informative exploration?

Just doing it is the success, regardless of how it turns out. Modern composers, it’s simply important to support them. We play hundreds of concerts and learn from all of them what works and doesn’t work. Composers learn that too. It’s important to perform new, untested works so that we keep spinning the cycle of new works.

You mention continuing the cycle. What are ways — other than commissions — the quartet contributes to the ongoing vitality of classical music?

For traditional audiences in concert halls or anywhere really, we like to break things down, to talk before performances so people don’t feel left out. The more difficult the rep, the more we explain things the audience can latch onto. We want them to understand the baseline; make them a part of the conversation.

House concerts are actually one of the most rewarding things for the quartet. People are closer and the experience becomes visceral. Especially for new audiences, because to get young people in the hall is tricky. They think it’s going to be stuffy. But house concerts in living rooms; people have drinks, get to know each other.

As ambassadors of classical music to young people who are less prone to listen to it on a regular basis, what is Telegraph’s approach?

We play faster, attention-grabbing pieces of music. We’ve learned we have to “speak” at a pacing they’re used to. This is a smartphone generation that gets bored, switches quickly to something else, then binges on it. Haydn, for example, it’s too slow. Oddly, when we play new music like Webern for elementary students, they love it. They think it sounds like nightmare movie music. Their creative juices really flow. Then, once they’re in the door, we show them how it’s similar to romantic and classical composers. Going the other direction (from classical to contemporary) doesn’t work nearly as well.

What might the quartet do to enhance your visibility?

We want to put up more videos, more fresh material for people. We all juggle three jobs: the quartet, teaching at the conservatory, and private studios. That’s just what it takes in the city we live in. More social media, that’s a topic we keep talking about though: How can we get stuff out there to keep people interested?

What would you like to see and hear more of in the Bay Area?

I always think I’d love for musicians in the Bay Area to be more genuine. Not do things because everyone else in society is interested, but from the energy of genuine interest. I’ve noticed that students especially follow what people are doing — so much so that they’re not sure what they actually want to do. I ask them, “What do you really want to do? Anything [you] want to do, not just music.” It’s shocking to me how often they say they don’t know.

Correction: The article as originally published misspelled Theo Bleckmann’s last name in the headline.