If you ask composer and instrumentalist Cheryl Leonard what she does, you’d get an ordinary answer right up to the point where she talks about the instruments she composes with. She uses objects found in the natural world — rocks, shells, pinecones, tree bark, the bones of long-dead penguins she found during a trip to Antarctica sponsored by the National Science Foundation. She also makes field recordings and turns them into musical pieces. And this has been her artistic practice for decades.

While it seems “out there,” the use of found objects and field recordings in European-style composition has been going on for 80 years or so and is common now. Other Minds, the Bay Area-based new-music organization, has been running a series called “The Nature of Music” since 2016, involving composers such as Annea Lockwood and, most recently, Hildegard Westerkamp. Not surprisingly, the first composer on that series was Leonard herself. Of her work, Other Minds noted, “Leonard is fascinated by the subtle intricacies of sounds. She uses microphones to explore micro-aural worlds hidden within her sound sources and develops compositions that highlight the unique voices they contain.”

By its very existence, Leonard’s work raises questions we often overlook. “All art is really driving people to perceive the world in new ways,” she says. “What is natural in an actual sense? Like, in Western culture we have this idea of natural as separate from human but really humans are part of nature. We don’t really have the language to describe how we’re part of nature; it’s very constructed.”

But there’s definitely not a dichotomy in Leonard’s work, more of a continuum. She’s trained in European art music, has a degree from Mills College, teaches piano from her private studio, and plays guitar and viola as well. “I studied piano and counterpoint and theory, I actually like analyzing pieces and I do think that makes its way into my music. I am thinking about form and structure in my pieces and development and motive and instrumentation,” she told me. Her pieces are layered and event-filled, it’s just that the events are often smaller scale than changes on conventional instruments.

It’s Leonard’s thinking outside the box, however, that attracted the attention of Christy Funsch, the choreographer and artistic director of Funsch Dance Experience, which she founded “to question representation, narrative, and conventional depictions of women through deeply investigated, specific movement vocabularies.” “I first heard Cheryl’s music and tales of her Antarctica field recordings through a mutual colleague. I was drawn to what I experienced as a mixture of natural and fabricated sounds,” Funsch recalled. She invited Leonard to be the musician for her planned 12-hour performance EPOCH, which premieres at the ODC Theater on Oct. 2 and is scheduled to run from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m.

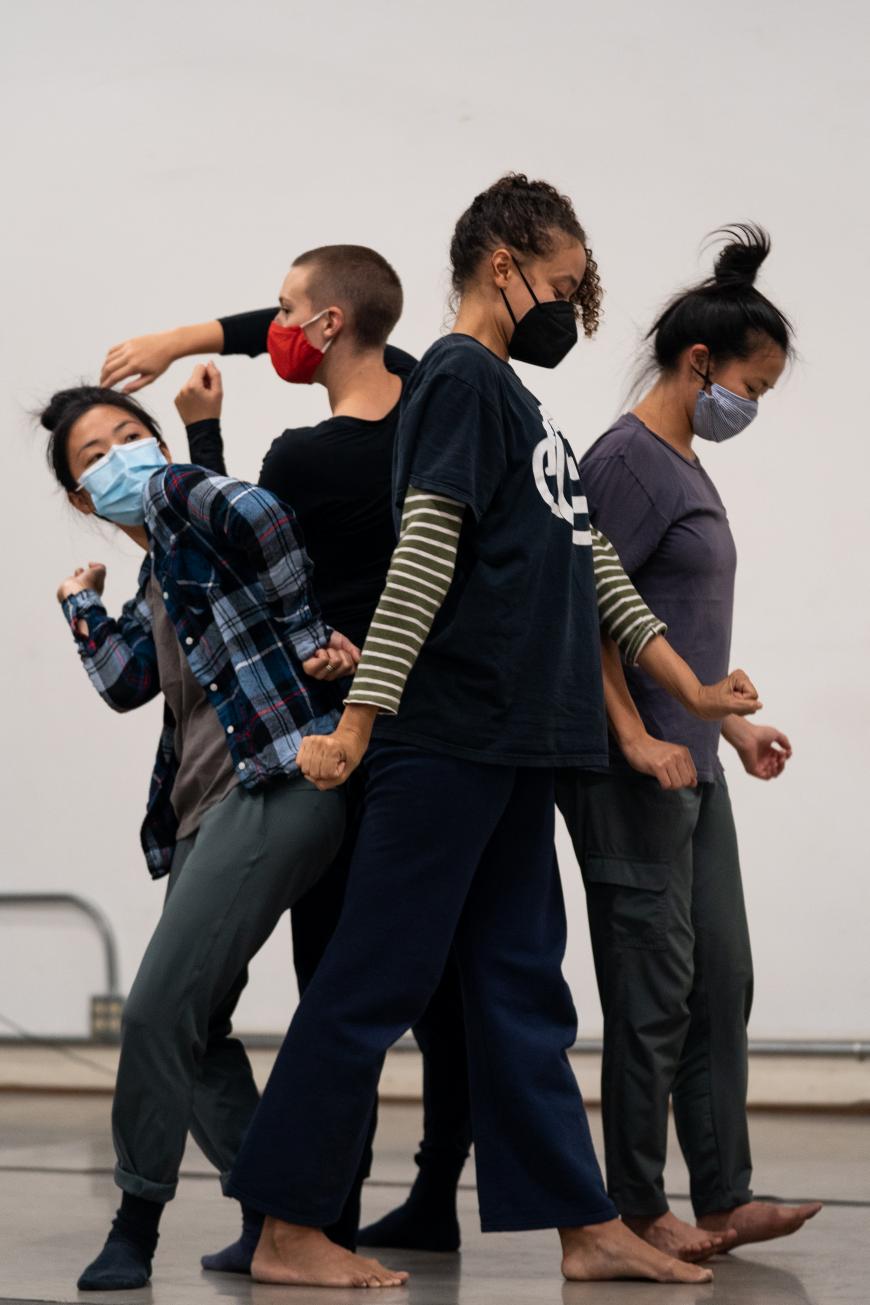

No one, least of all Funsch, expects audiences to sit through the whole thing. The audience is expected to come and go throughout the day. “I wanted to design a performance event that invited lingering, in defiance of the constant and frenetic hustle that so many of us operate in,” Funsch wrote me. “In EPOCH, I have set up parameters for performers to practice what they excel in — being present. This virtuosic ‘beingness’ is complicated by the duration; and still they are excelling!” As the work goes on, the audience will experience what they might think of as “down time.” “Moments of nothingness are, to me, moments of unconventional performativity (sincere eye contact) and/or chore-based action (e.g. sweeping a floor),” Funsch explains.

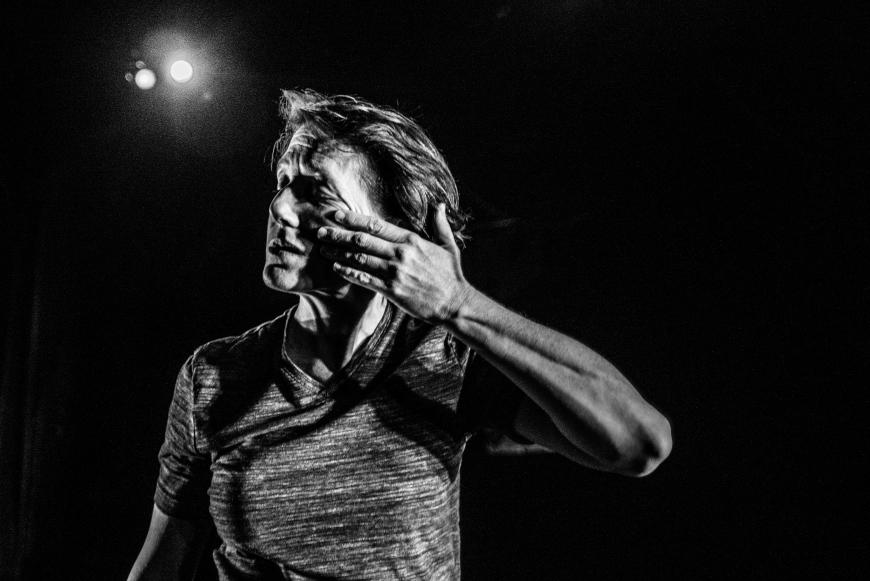

Leonard, like all the performers, had “nothingness” work to do: “My devotional task was going out into the Marin Headlands and doing field recordings and hiking around, listening to the landscape. And so, we hired a camera person to follow me and film me just doing that and improvising. So, these videos of me out in the Marin Headlands — again, not trying to do a performance but experiencing a place through sound and physically moving around in the space, that’s also part of the performance.”

EPOCH is designed to oppose art as a consumable good by creating something that can’t be defined in the usual ways that a capitalist society would think about art, a piece that would highlight another possible set of values. Leonard clued me in to one of the inspirations for the piece:

So, one of the things we’ve talked about is Norwegian slow TV. Do you know about that? In Norway, there was a producer at the public TV station who had this idea to literally just put cameras on the train that goes from Oslo to Bergen — no actors, nobody’s doing anything — and people could just tune in for the length of that train ride and just, like look out the window of the train. And people loved it. And then they took the same concept and put it on the Hurtigruten Ferry that goes all the way up to the Arctic. And that’s like 10 days or two weeks or something. Again, impossible to consume the whole thing — you just can’t stop your life for two weeks and watch the camera on the ferry. But people loved it. They would pop in and out and it became an unexpected hit.

So, we’re not doing slow TV, but we’re reframing what a performance could be.”

EPOCH’s scale is such that Leonard also plays a 50-minute set of three of her pieces in the performance, playing them live three times with different dancers. Recorded versions of the pieces then accompany other segments. Only one of them, Unstable Material, was created specifically for this performance and is based on the sound recordings she made at the Marin Headlands. “I was listening to birds and the ocean and then the buoys. There’s this one buoy that my friend says sounds like a cow. But I really like it, it’s like a sigh of the ocean. And then there’s wind going through different things and then I started recording the wind and the waves resonating inside the bunkers — or the ventilation pipe of the bunker.” In the piece, the sounds are layered but not processed.

Leonard prefers to talk about her art in practical terms and that’s how she explains her process: she’s responding to a series of challenges or moments of discovery and trying to realize the art in the most direct way possible. She began to participate in the “noise music” scene as soon as she got to San Francisco in the 1990s. (Noise music is playing “junk,” found manmade objects.) But since she loved to hike, backpack, and go mountaineering, she began to notice natural sounds as well.

When I was out there, things would happen. You’d be walking on a trail and kick a rock and it would sound musical. Like, it would have a beautiful pitch. ‘Wow, that’s a great rock, maybe I should take this back and play it.’

I started building instruments, mainly as a way to make it easier to play the natural objects. So, I wanted to play a shell but it’s really awkward to hold it in one hand and bow with the other and then pick up another shell. So I had to mount the shells in a way that made it easy to play and then that became a whole practice — sort of a musical sculpture thing. These all just evolved (pardon the pun) naturally.”

By contrast, Funsch’s work seems to proceed from larger concept to working out. She’s also giving creative agency to dancers and other choreographers in order to move the performance beyond a single viewpoint. “I flipped the temporal scale of the work,” she explained. “One day I made one-minute movement studies every hour on the hour for 12 hours. These were then given to a subset of performers who developed movement vocabularies from this footage. This footage was then shared with a wider group of performers until, telephone style, we arrived at EPOCH’s full vocabulary. There is a collective, unifying language and also vibrant individuation of this language.”

Beyond that, Funsch has included “wrecking” in EPOCH. Funsch elaborates, “Wrecking is a process first developed by choreographer Susan Rethorst in the 1990s wherein a guest director assumes control over the in-progress or finished work. For my current process of making EPOCH, I wanted to bring in several BIPOC colleagues to help reveal (some of) my biases and defaults. Short studies from these sessions will be performed and discussed during the 6 p.m. hour of the EPOCH performance.”

For Leonard, the work on EPOCH has been an epic. As the event approaches, she’s putting the finishing touches on the recordings of works that she composed from her Antarctic trip back in 2008, and she has a new album out (Schism, on the Mappa label, available on Bandcamp). But the three years she’s spent on this work has created a visceral interest in seeing it come to fruition, were it not for the impossibility of taking in the whole thing. “I would like to watch the parts that I’m not performing,” she says, “but I don’t even think I can.”