Wadada Leo Smith was there at the birth of ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) in 1969. The trumpeter and composer didn’t end up releasing an album on the Munich-based label until a decade later, but it’s more than fitting that his Golden Quintet is the centerpiece of SFJAZZ’s 50th-anniversary celebration of a label that has both shaped and documented music by many of the era’s most influential artists in jazz and classical music.

An early member of Chicago’s experimental-minded Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Smith had performed several times with German bassist Manfred Eicher in the late 1960s, including a concert with alto saxophonist Marion Brown (who recorded the fourth ECM release, Afternoon of a Georgia Fawn). He recognized Eicher as a stellar musician, but had no way of knowing that his vision would manifest itself on a label with a singularly coherent aesthetic.

“The name ECM came out of a conversation I had with Manfred when he started to strategize about starting the label and I suggested Editions of Contemporary Music,” says Smith from his home in New Haven, Connecticut. “Once it got going I find out that he’s one of the 20th-century’s greatest producers and engineers, a thinker who developed an aesthetic that’s reflected in ECM’s records. That aesthetic is the way Manfred hears the music.”

When people talk about an “ECM sound” they’re usually referring to the feel of spaciousness on the label’s recordings and a crystalline clarity in which every note is well-defined. With cover art featuring photos of abstract imagery or color-washed landscapes, ECM albums came with a look as distinctive as the music contained inside. Sometimes the label gets pigeonholed as a redoubt for Northern European jazz artists who often draw on Scandinavian folkloric sources for inspiration. But from the very beginning, Eicher sought to record improvisers associated with the African-American avant garde. While many early ECM releases focused on various schools of free improvisation, Eicher always cast a wide stylistic net, championing the early fusion of Return to Forever and the exploratory post-bop of pianist Paul Bley.

Rapidly gathering momentum in the 1970s, Eicher produced a vast and beloved catalog of ECM that encompasses numerous releases by Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea, the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Paul Motian, Pat Metheny and John Abercrombie, Dewey Redman and Jack DeJohnette, the British reed player John Surman, Moldavian pianist Misha Alperin, Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem, and Brazilian multi-instrumentalist and composer Egberto Gismonti (who performs solo at SFJAZZ on Sunday, Oct. 27).

The SFJAZZ series opens on Thursday with Armenian pianist Tigran Hamasyan, whose extraordinary 2015 ECM album inspired by folk and sacred music Luys i Luso commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. He’s joined in Miner Auditorium by Armenian-American vocalist Areni Agbabian, who released Bloom, her gorgeous ECM debut focusing on her original songs, in April.

On Friday Oct. 25, Wadada Leo Smith’s quintet shares a double bill with Israeli trumpeter Avishai Cohen’s quartet in Miner, while downstairs Bay Area-raised bassist Larry Grenadier celebrates the release of his album The Gleaners with two solo recitals in the Joe Henderson Lab (he also plays solo at San Jose’s Art Boutiki on Oct. 26). Grenadier started recording for ECM around the turn of the century with tenor sax star Charles Lloyd’s group, starting with 2000’s The Water Is Wide. But those sessions were in Los Angeles, and a later date with Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava took place in New York. It wasn’t until the second and third releases by the collective trio Fly with drummer Jeff Ballard and tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, 2009’s Sky & Country and 2012’s Year of the Snake, that he worked directly with Eicher.

“The thing that’s unique in jazz is that he’s super hands-on at times,” says Grenadier, a longtime member of pianist Brad Mehldau’s trio. “He’ll walk into the studio and move the mic a few inches and it sounds better. With Fly, he had some really helpful suggestions about the form of the arrangements and tempos. He makes quick judgements about whether a tune is appropriate. That could be tricky for some people, but I’m always looking for another set of ears. Sonically, I grew up with that ECM sound. People say it’s the reverb, the space of the room, the space around the instruments. As a bassist, ECM always had the best recorded bass sounds. I go to ECM records for the bassists I love.”

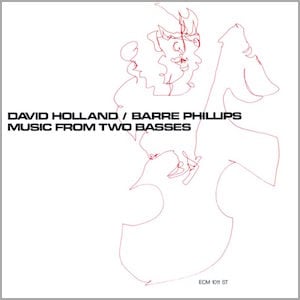

Grenadier hadn’t really thought of recording a solo project until Eicher suggested it. ECM has a long track record of bass-centric albums, starting with Barre Phillips and Dave Holland’s 1971 album Music From Two Basses. Grenadier spent a year developing the music and the concept for the album, which was partly inspired by the wondrous 2000 Agnès Varda documentary The Gleaners and I. While he uses overdubbing on two tracks, he created a program that he could perform in concert.

“I spent a year doing a lot of practicing,” he says. “It was a push musically and conceptually to hone in on the fundamental aspects of what I try to get out of the instrument. The bass is technically unwieldy, fretless with a low register that makes it inherently unclear. The practice has always been to bring out the clarity.”

Saturday’s program features a new version of pianist Vijay Iyer’s trio in Miner Auditorium with bassist Stephan Crump and Jeremy Dutton, a brilliant young drummer from Houston. Drummer Peter Erskine plays two shows in the Joe Henderson Lab with his Los Angeles trio-mates pianist Alan Pasqua and bassist Darek Oles and tenor saxophonist George Garzone, a Boston institution who’s making his San Francisco debut at 69.

The group released a powerhouse live double album last month on Erskine’s label Fuzzy Music, 3 Nights in LA, but the drummer has played on at least a dozen ECM albums, including three sessions of his own with British pianist John Taylor and Swedish bassist Palle Danielsson.

For music fans familiar with Erskine’s playing in two era-defining fusion bands, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul’s Weather Report and vibraphonist Mike Mainieri’s Steps Ahead, the luminously lyrical ECM trio sessions came as something of a surprise. While Erskine says that “every ECM album is really a collaborative project,” the drummer had to adjust to a new dynamic in the studio as the leader of a session that Eicher produced.

“The terrain feels a lot less friendly,” says Erskine, who also performs with the quartet at Kuumbwa Jazz Center on Monday Oct. 28. “He’s liking some pieces but not liking others and you can tell when you look in the control room. If he likes a piece he might be dancing, or might hit the remote button and talk to you in the headphones. If he didn’t like it, he’d be reading the newspaper, sort of holding it up like a married couple when one spouse is annoyed with the other. If he really didn’t like it, it would be a Norwegian newspaper, because he didn’t read Norwegian. If he reallllly didn’t like it, the newspaper would be upside down.”

The ECM series closes on Sunday Oct. 27 in Miner Auditorium with Egberto Gismonti, who’s recorded more than two dozen albums for ECM as a leader or co-leader. Downstairs, trumpeter Ralph Alessi presents his band This Against That with saxophonist Jon Irabagon, pianist Andy Milne, bassist Drew Gress, and drummer Mark Ferber (the same group also performs Tuesday, Oct. 29 at Fresno State). And by coincidence, Cuban pianist David Virelles, who’s recorded two albums for ECM and played on acclaimed sessions by trumpeter Tomasz Stanko and saxophonist Chris Potter, performs at UC Berkeley’s Hertz Hall on Sunday Oct. 27 as part of a new Cal Performances jazz series curated by pianist Myra Melford. More than an inescapable part of the cultural landscape, ECM continues to expand musical horizons half a century after appearing on the scene.

Correction: The original article misidentified Wadada Leo Smith’s home as Newark, New Jersey.