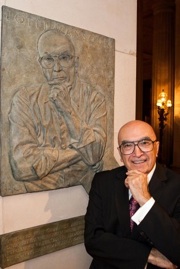

Mansouri Unveiled

Photos by Drew Altizer

Old and frail, when Otto Klemperer came to the dress rehearsal of La traviata at the Zürich Opera in 1960, he sat down next to the director, and promptly fell asleep, resting his head on the young man's shoulder.

Providing the impromptu pillow for Klemperer's nap was a petrified Lotfi Mansouri, who was at his very first major production awaiting the music director's verdict, something normally provided while awake.

The happy ending of the story, as told by Mansouri Monday night at the unveiling of his bas relief in the lobby of the War Memorial Opera House: Klemperer awoke with a start as Violetta hit a high note, and told Mansouri "Wonderful! We'll do Fidelio together."

From the "dusty streets of Teheran," where he first encountered opera — at the movies, where, he says, he heard Deanna Durbin sing "Nessun dorma" — Mansouri made his way to Los Angeles. (I recall Mstislav Rostropovich once saying that Durbin's "musical purity" influenced him greatly in his youth.)

In L.A., Mansouri's classmates included Arnold Schoenberg's daughter, he had lunch with Alma Mahler ("I had no idea who she was"), started the friendship of a lifetime with Carol Burnett, and made his debut with the San Francisco Opera. He was a super in Otello during one of the company's many visits to the Shrine Auditorium. Later, he worked as an usher, and — a few years later — became the San Francisco company's fourth general director.

Much was said last night about the years between the 1960s and 1988, when he began his intendancy, a good deal by current General Director David Gockley (who just turned 24 when he first met Mansouri on an occasion involving a fair measure of alcohol, he recalled even after all this time).

Mansouri is 80, which is apparently the new 60. He looks "mahvelous," even if the plaque unveiled does not. Bruce Wolfe, also the sculptor for the bust of Kurt Herbert Adler in the lobby, created an image (said to be the second, after the rejection of the first), which shows someone studious, self-effacing, remote — everything Mansouri isn't. Strange are the ways between self-image and "as others see us."

At any rate, his image is there now, along with those of Gaetano Merola (1923-1953), Adler (1953-1981), and Terence A. McEwen (1982-1988). Mansouri's years as general director were 1988-2001. He didn't actually move to San Francisco until 1989, and that's when the roof fell in, and the Loma Prieta Quake necessitated the rebuilding of the Opera House, which also brought Mansouri's greatest achievements. (He spent the 15 seconds of the quake under the desk in his office — a desk "with a marble top.")

Raising the needed $90 million (when that was "real money") was just the beginning of that saga of the survival, or better yet, the flourishing of the only major opera company ever to conduct regular seasons without its home. FEMA contributed $50 million, the city's War Memorial complex $10 million, and the rest was raised from private donations.

In 1996-1997, not only were a dozen S.F. Opera productions in the Civic Auditorium, the Orpheum, and elsewhere, but Mansouri's "Broadway Bohème" brought in new and younger audiences. Gockley said the average age dropped from 54 to 31 — something quite incredible when looking around the audience these days on either coast.

Mansouri's speech at the unveiling was both hilarious and touching in his many generous acknowledgments of those he worked with, from the head of the board (William Godward, "who knew what kind of blue the ceiling was because he had attended the opening of the house" [in 1932]) to the props department (Lori Harrison, "who spent three months in Paris, paying her own way, to get the props exactly right").

Mansouri is directing in San Diego ("Nabucco" and others), will receive the NEA Opera Honors Award for his introduction and championing of supertitles, and his autobiography will be published early next year. It's sure to be a best-seller among both opera fans and aficionados of offbeat, gently ribald stories.

Sheik-Wainwright Switch

Rufus Wainwright's San Francisco Symphony-commissioned song cycle, Five Shakespeare Sonnets, will not premiere at Davies Symphony Hall next April, "due to scheduling conflicts." It is now expected a year from now.

Tony- and Grammy-winning singer/composer Duncan Sheik will replace Wainwright in the April 7-10 concerts, performing the world premiere of a song suite from his new work Whisper House, with the orchestra.

Whisper House follows Sheik's Broadway hit Spring Awakening (which played at the Curran Theater here a year ago, and which is playing in San Jose Oct. 28-31), was cowritten with Kyle Jarrow, and will premiere as a theatrical work at the Globe Theater in San Diego in January. The suite is commissioned by the S.F. Symphony.

News of Paul Moor

Although Texas-born, Berlin-resident music critic Paul Moor was active in San Francisco decades ago, chances are that many still remember him and read his Musical America reports.

After a long period of uncharacteristic silence from him, information was posted on his Web site about a stroke he suffered — and survived. Read the Web site appeal for messages to be sent to him at [email protected].

An 'Urgent Case' for Consolidation

When he became general manager of the San Francisco Opera, David Gockley says he was "amazed" to learn that company activities are spread over seven venues, including the scene shop near Potrero Hill, rehearsal spaces in the Presidio — considerable distances, usually through heavy traffic.

"Being scattered as we are is not only costly," Gockley says, "it is staggeringly inefficient.

It takes time and money to move people and materials from one space to another. It is also a very difficult situation for me to manage and keep track of, rather like a mother country trying to administer a number of distant colonies.Gockley advocates a plan of consolidation for the sake of efficiency and economy:Would you believe that since 1980 we’ve spent more than $40 million in supporting this ramshackled system, including costs for leases, trucking, staff time, transportation, and labor? If only that money could be spent on the art or providing some budgetary relief, or for a building!

If I could leave one legacy to this company at the end of my stint, it would be a centralized facility that not only accommodates production shops, rehearsal and storage spaces, and offices, but also houses a wealth of learning and community activities centered on opera. This would provide a "center of life" for the company so a sense of unity and family can flourish.Gockley recognizes the "mammoth hurdles" to overcome legal, bureaucratic, and even political factors on the way to an optimal solution: "This is by all means still a dream, but anything of enduring value starts with a dream."A once-in-a-century opportunity for such a center may exist in the next several years. The Veterans Building, our next door "twin," is scheduled to close for a much-delayed seismic retrofit in the next several years. It presents an ideal chance to add a matching addition to the building on the Franklin Street side to balance the addition to the Opera House. The space and proximity are ideal.

Opera and Architecture

Both The New York Times and The Financial Times have fascinating reports on Dallas' new performing arts center.

The latter is especially interesting in placing the buildings in cultural context, although it doesn't review the opera house's acoustics; perhaps it was written before the sound could be judged. (It's "acoustically lively," says The Times review of opening night.)

From Edwin Heathcoate's Financial Times article:

"Dallas," said architect Rem Koolhaas at a packed lecture for the opening of the city’s new performing arts centre last week, "is the epicentre of the generic." A ripple of slightly nervous laughter floated around the auditorium of his new theatre. Only Koolhaas can insult the city that has just paid for his new building and make the audience feel privileged to have their city insulted. He can get away with it because he has just conferred on Dallas a magical new theatre and everyone is happy to be sitting in it. To have it here. Of all places.The $354m Dee and Charles Wyly Theatre and the neighbouring Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House by Foster + Partners are the latest instalments in the stuttering history of Dallas’s Arts District, a long-running project that is rather ambitiously trying to surpass New York’s Lincoln Center as the nation’s premier arts centre. Anchored by the underrated Dallas Museum of Art, designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes (1984), and the monumental, not entirely beautiful Morton H. Myerson Concert Hall by IM Pei (1989), the project is also an attempt to give the city a soul.

Although Los Angeles is often dismissed (and misunderstood) by Europhiles as a city with no centre and no heart, Dallas would be the better example. Its central business district is a melange of defunct US tropes: mirror-glazed blank-slab offices, massive multi-storey carparks, conference centres that have the size and aspect of walled cities. But they have their own interest. These are the archetypes of modernity; any visit to the Middle or Far East shows that this is the architecture of today. Koolhaas is right: Dallas, despite its failure as an urban model, remains the exemplar for corporate cities in hot climates.

The Arts District is the cultural version of that city. Here star projects sit in self-satisfied isolation, unrelated to each other, unconcerned. Valet parking attendants ensure that patrons arrive and depart without being contaminated by any sense of urban life. The two new buildings try, and broadly fail, to address the problems. Yet they are far from failures in themselves.

A Historical Trout Quintet

When they were all young, Itzhak Perlman, Daniel Barenboim, Jacqueline du Pré, Zubin Mehta, and Pinchas Zukerman got together in London to perform Schubert's Trout Quintet. Before the performance, the young future giants horsed around, in this outtake from Christopher Nupen's Remembering Jacqueline du Pré.

The entire performance can be seen in these consecutive YouTube segments: one, two, three, four, five, and six.