Forty-nine porcelain ramekins — the kind you’d normally use to bake a souffle — will become an instrument for exploring freedom at the CounterPulse arts space in San Francisco.

For more than 50 minutes, German performance artist David Brandstätter will dance on these fragile cups, suspended four inches above the ground. At times, he’ll shuffle around on four cups: one for each hand and foot. At others, he’ll glide around the stage using two cups, arms flailing, like a novice ice skater trying not to lose balance.

Freedom, for Brandstätter, is a risky balancing act (in fact, one so risky that he’s shattered some 30 cups in rehearsals).

“I invite the audience on a meditative journey around the idea of freedom and its implications for an individual as well as for society,” Brandstätter said. “By sharing my own history and critique, I give space to the audience to reflect upon their personal notions of freedom as well.”

Brandstätter’s piece, FRE!HEIT (German for “freedom”), will have its U.S. premiere courtesy of the San Francisco International Art Festival Oct. 7–9. It will mark the first time the work is being performed since the onset of the pandemic, which, for many, altered their perceptions of freedom.

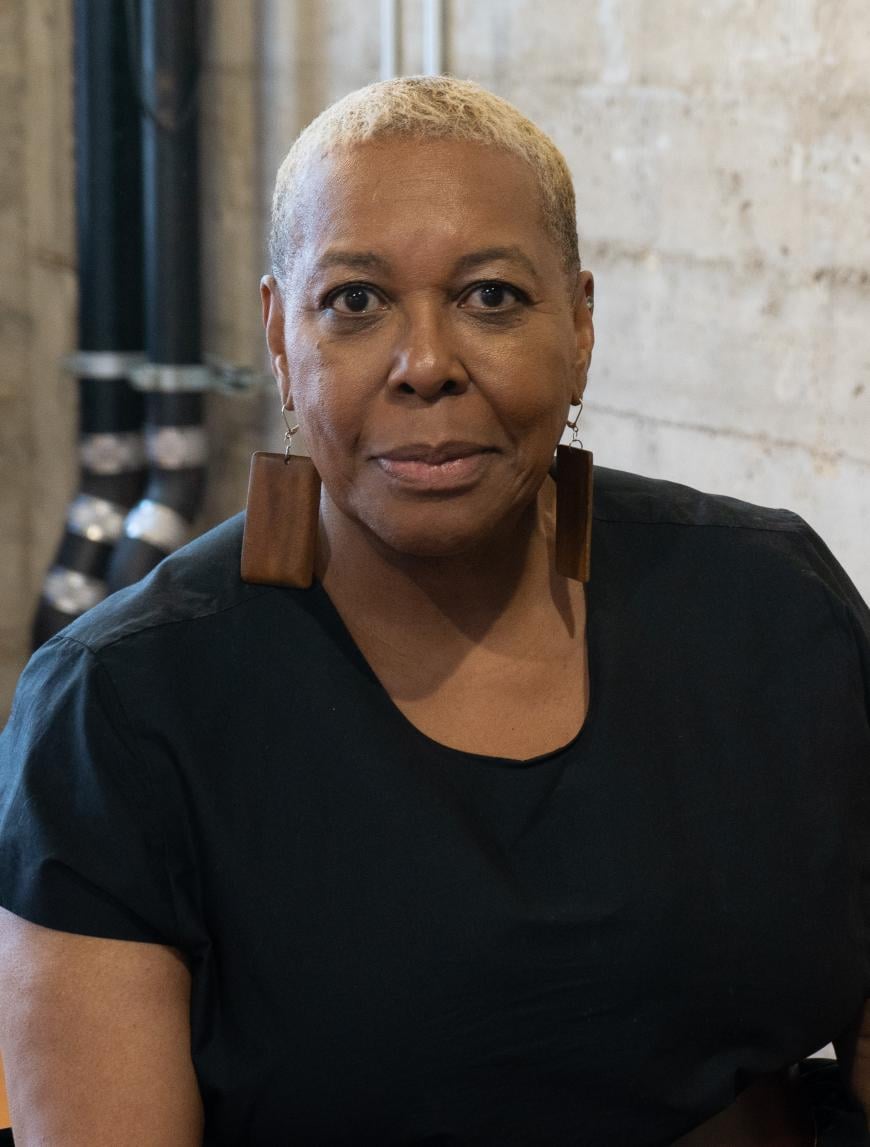

What makes FRE!HEIT distinctive, aside from its unconventional use of ramekins, is the fact that Brandstätter and a new guest artist alter the accompanying text depending on what city and country they’re performing in. (More on that later.) Joining Brandstätter in the San Francisco iteration of the work is Michelle Jacques, an Oakland mezzo-soprano who will narrate and sing works including Richie Havens’s “Freedom” and the Beatles’ “Blackbird.”

“We’re taking these two people from opposite ends of the earth, opposite sexes, opposite skin colors,” Jacques told SF Classical Voice during a phone call. “We’re combining this expression into one, and it’s almost the same, even though we’ve come from different places and we have different thoughts and different ideas.”

Accompanying the sung, spoken, and occasionally prerecorded text is the loosely percussive noise — or music, if you subscribe to John Cage’s philosophy that any sound can be material for a composition — that moving cups make. And Brandstätter pays close attention to the sounds he’s producing throughout: a soft shwoop, shwoop as porcelain under pressure scrapes against the floor; a click as two cups are stacked on top of each other.

“Sometimes, I’m lucky, and there’s a nice combination of sounds that comes out,” Brandstätter told SFCV. “Every cup has a different pitch, depending on where it was in the oven.” The cups on the edges of the oven tray, he explains, carry a distinct, brighter sound. The one in the center is usually the lowest in pitch.

Relief and Release

Brandstätter became fascinated by the notion of freedom in the wake of his father’s death. On one hand, his father’s passing after four years of being in a coma came as a relief. His father had been liberated from his suffering, and his family had been released from the heavy burden of seeing a loved one deathly ill. Yet it meant Brandstätter shouldered new responsibilities as the oldest man in his close family, he says.

He knew he wanted to create a piece about freedom but couldn’t pinpoint exactly why he still felt unfree. “It was at a point where I had made the discovery that when I used the word ‘freedom,’ I was not really sure what I spoke about,” Brandstätter said.

So he fell into a rabbit hole of philosophical texts, including those of Immanuel Kant, who draws a distinction between internal freedom (“feeling free”) and external freedoms (including freedom of speech, freedom to move across borders, and political freedom).

This philosophical content, combined with Brandstätter’s own stories, form the base for FRE!HEIT. Brandstätter grapples with, but makes clear that he can’t provide answers to, the following questions: What is freedom? And what is freedom demanding from us? Is freedom even a task?

There’s a tense moment in the piece when Brandstätter leans down to pick up several cups, stacking them to make a tower, all the while standing on two cups. It’s intended as a commentary on the verticality of a social hierarchy, he says. “I found a lot of freedom inside the hierarchical structure of the Confucianism-organized society of South Korea,” he observed, paradoxically.

Taking Freedom Global

Brandstätter conceived FRE!HEIT as an introspective solo work in 2013. It’s since evolved into a collaborative, multidisciplinary piece that features a guest artist native to the region he’s performing in.

The idea of expanding the work initially came to Brandstätter when he was invited to perform FRE!HEIT at a 2019 arts festival in Tunisia. He was aware he’d be presenting his piece to an audience whose vision of freedom would likely be defined by recent revolution, and he thought it would be best to find someone who could serve as a cultural mediator and add a layer of complexity to the work.

“I had the feeling … that whatever I have to say may be interesting to some people, but it’s in a way also ridiculous in comparison to the very recent history of the country,” Brandstätter said. “I would have to live for a year or two in a country to understand just a little bit of it. I felt I needed a local voice in order to, first of all — [and] also to learn from their perspective.”

When he reached out to Tunisian journalist and activist Henda Chennaoui, she was slightly skeptical, having never partnered with an artist on a piece like this before. But she took a leap of faith, agreeing to write a portion of the text.

Chennaoui wrote poetry about specific kinds of freedom that she was fighting for: of expression, of political organization, to exist as a citizen, to exist as a feminist woman. “And it was always about this political fight and solutions — how we will implement freedom in the law, in the state, in the culture, etc.,” she said.

Over the course of his meetings with Chennaoui, Brandstätter realized FRE!HEIT was more powerful when it was repurposed as a collaborative effort: a conversation between himself, the guest artist, and the audience.

When he brought it to Pakistan, he found a local music ensemble to collaborate with. It was again successful; the change remained.

A FRE!HEIT for America

“I thought it was the strangest thing I’ve ever heard in my life,” Jacques said, on her initial reaction to the piece. She laughed. “I was like, ‘What the heck?’ And I went on YouTube, looked at it, and was still like, ‘I don’t get it.’”

It wasn’t until they started rehearsing, she said, that she started understanding the beauty of the piece. “Now, I’m so excited to be a part of it,” Jacques said, adding that she and Brandstätter have become dear friends in a matter of months, bonding over their shared love for humanity and their mutual nerdy artist-ness.

“Working with Michelle on this particular version is a blessing,” said Brandstätter. “We share an intuition for details and nuances that make the process of rewriting a joyful ride of sharing ideas and give-and-take. It feels like we have known each other for years.”

Jacques is particularly excited about her inclusion of the Beatles’ “Blackbird,” a song that immediately came to her mind when introduced to FRE!HEIT’s concept. It was written by Paul McCartney after witnessing racism firsthand. In English slang, “bird” refers to a woman or girl. From the opening lines, “Blackbird singing in the dead of night / Take these broken wings and learn to fly,” “Blackbird” offers an uplifting message of freedom and hope to Black women.

When Jacques, an African American woman born in New Orleans, Louisiana, and raised in Oakland, thinks about freedom, she thinks of freedom from bondage. “We have a long way to go in this country,” Jacques said. “There’s no compassion anymore. There’s no love anymore. There’s so much divisiveness and distrust and hatred.”

She’s traveled the world as a musician but still hasn’t managed to find the freedom she believed she was close to finding. At times, she said, it feels like reaching for the stars, only to find that something’s pulling your hand away.

Jacques said she hopes audiences will walk away from FRE!HEIT with feelings of peace, love, and joy. As for Brandstätter, he hopes people will be comforted and relieved. “It’s this feeling of ‘finally, I’m not the only one with these stupid thoughts,’” he added with a smile.