Delving into the newly expanded edition of Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era is to fully appreciate L.P. Hartley’s canny aphorism that the past is a foreign country. A lovingly tended collection of photos and oral histories acquired over some three decades by interviewer and writer Elizabeth Pepin Silva and photo editor Lewis Watts, the book offers a portal into what was once a thriving African-American neighborhood thrumming to the beat of jazz.

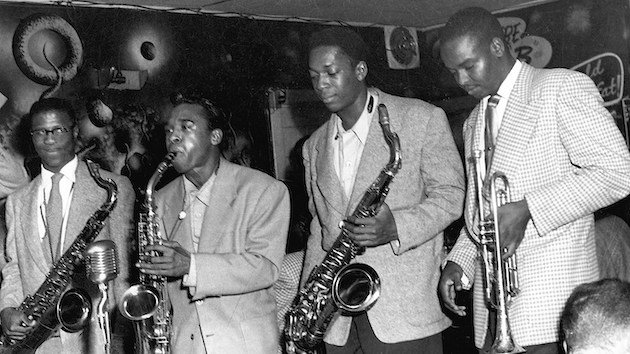

The music vibrates through the black and white images, which capture street scenes and night clubs, store fronts and neon-lit marquees, crowded bandstands and stylishly dressed patrons out for a night on the town. Ultimately, it’s a story of loss and indifference, as racially-targeted urban renewal projects started uprooting the neighborhood in the mid-1950s, shuttering Black-owned businesses and scattering long-time residents throughout the region.

The music vibrates through the black and white images, which capture street scenes and night clubs, store fronts and neon-lit marquees, crowded bandstands and stylishly dressed patrons out for a night on the town. Ultimately, it’s a story of loss and indifference, as racially-targeted urban renewal projects started uprooting the neighborhood in the mid-1950s, shuttering Black-owned businesses and scattering long-time residents throughout the region.

Originally published in 2006 by Chronicle Books and briefly reissued as a self-published volume in 2017, Harlem of the West is now available via Heyday Books as a handsome hard-bound tome. The updated edition adds 100 pages to the original version, with dozens of new photos, additional interviews, and many elaborations and corrections. Silva and Watts benefited from the book’s initial success, which coaxed the neighborhood’s former residents and their descendants into sharing photos and stories long filed away.

“Everyone talks about the dumpsters, things being thrown out right, left, and center,” Silva said from her home in Ojai. “So much history was lost or scattered. People left and had to find new places. For the first edition, we couldn’t find any copies of The Sun-Reporter, the Black newspaper that started publishing in 1943. A few years ago, the UC Berkeley library dug out a cache and then put them on microfiche, which I got down here through an interlibrary loan. I read every page from 1951–1960. It took me three months and answered so many questions.”

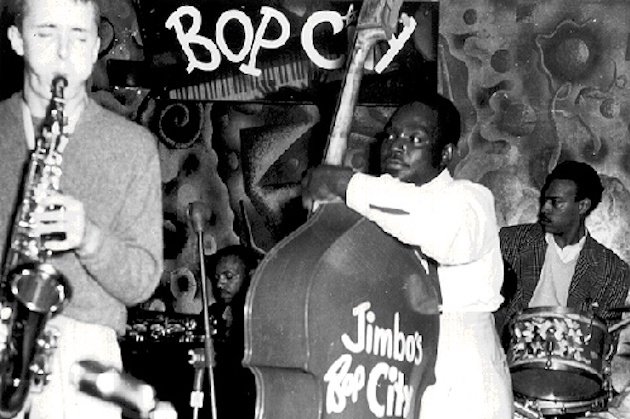

Some of the images have become oft-reproduced classics, like Steve Jackson Jr.’s shot of Charlie Parker putting his alto sax away at Jimbo’s Bop City, his open horn case resting on a table with a chair permanently reserved for heavyweight Ezzard Charles. But it’s the granular detail of the stories coupled with the photos, which capture entertainers, celebrities, employees, proprietors, and neighborhood denizens who filled the Fillmore with such vitality.

Silva was 22 years old in 1986 when she started to focus on the neighborhood’s faded past. Newly employed by Bill Graham, she was given a vague directive to find out what she could about the history of the Fillmore Auditorium. When the usual resources like the San Francisco Public Library and the California Historical Society turned up empty, she expanded her mission and started gathering first-person accounts. With a healthy mix of naïveté and dauntless youthful energy, she approached people on the street who looked old enough to have experienced the neighborhood in its mid-century heyday.

“One of the challenges when I started this project is that the traditional sources for history didn’t have almost anything on this neighborhood,” Silva said. “The new edition builds upon 35 years of people knowing that we were doing this project, getting a hold of us, digging out photos. The advent of the internet and the availability of materials that I didn’t have access to allowed us to add so many details.”

Drawn to the project by her love of music — as a teenager Silva had caught then-forgotten R&B great Charles Brown at Dottie Ivory’s Stardust Lounge — she found people connected to many of the venues that made the Fillmore such a creative hothouse. Harlem of the West offers intimate glimpses inside many of the district’s key establishments, such as Club Flamingo, the Plantation Club, the Blue Mirror, the Primalon Ballroom, the California Theatre Restaurant (“sepia floor shows nightly”), the Havana Club, Jack’s Tavern, and of course Jimbo’s Bop City, the afterhours spot where musicians gathered to jam until the wee hours.

Silva elicited some of the most vivid and telling stories from musicians remembering the long nights at Jimbo’s, accounts that capture the way the community’s embrace of musical innovation was woven into the scene. In the mid-1950s, the Bay Area’s best-known jazz spot was probably the Black Hawk in the Tenderloin, where progressive artists like Miles Davis, Cal Tjader, and Dave Brubeck recorded live albums. But San Francisco’s jazz scene was mostly known as an avid redoubt for New Orleans-style jazz. Sometimes called Dixieland but usually referred to today as trad jazz, various iterations of the New Orleans style hewed to the pre-swing-era polyphonic approach of the 1920s.

The trad scene featured Black players who helped create the style, like bassist Wellman Braud, trumpeter Bunk Johnson, trombonist Kid Ory, and bassist Pops Foster, and white musicians who came up in their wake, like Lu Watters, Turk Murphy, Leon Oakley, Wally Rose, and Bob Scobey. Rather than looking back to early jazz idioms, Black audiences in the Fillmore responded more to artists developing new sounds, and they embraced modernist saxophonists Teddy Edwards, John Handy, Dexter Gordon, and Pony Poindexter.

But the scene didn’t only nurture aesthetic innovation. “The Fillmore had an impact on all the African-American music scenes along the West Coast, from Spokane and Seattle down to Los Angeles,” Silva said. The driving force was entrepreneur Charles Sullivan, “The Mayor of the Fillmore” who engineered the creation of Jimbo’s Bop City and turned the Fillmore Auditorium into a major hub for Black acts like Little Willie John, Ray Charles, and James Brown.

“He was the largest promoter of Black music west of the Mississippi,” Silva said. “Once he started booking the Fillmore in the early 1950s, he became ‘The Guy.’ While LA certainly had a larger scene for jazz, blues, and R&B, I would argue that Charles Sullivan had a bigger impact because of his booking prowess.”

The fascinating collision of art and commerce plays out in another new book that details the key nightspots of mid-century America, Jeff Gold’s Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s. Where Harlem of the West drills down into the neighborhood’s nitty gritty, Sittin’ In takes a wide-angle look at the same era. It’s a celebration of mid-century cool, when popular culture designed for adults effortlessly existed as art and entertainment.

The fascinating collision of art and commerce plays out in another new book that details the key nightspots of mid-century America, Jeff Gold’s Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s. Where Harlem of the West drills down into the neighborhood’s nitty gritty, Sittin’ In takes a wide-angle look at the same era. It’s a celebration of mid-century cool, when popular culture designed for adults effortlessly existed as art and entertainment.

Focusing on the East Coast (New York City, natch, Atlantic City, Washington D.C., and Boston, while strangely leaving out Philadelphia and Baltimore) and the Midwest (Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City, and St. Louis), Gold loses steam by the time he crosses the Rockies, with only Los Angeles and San Francisco making the West Coast cut. While nodding to North Beach, San Francisco’s primary entertainment district for nearly a century, the SF chapter focuses on Jimbo’s Bop City, echoing the accounts from Harlem of the West. Still, Sittin’ In offers invaluable national context for understanding the vitality evident in the Fillmore.

But the closest and most essential companion to Harlem of the West is a book originally published in 1982 and reissued by the California Historical Society and Heyday Books in 1998, Tom Stoddard’s Jazz on the Barbary Coast. A seminal work that disrupted the myth that jazz’s birth in New Orleans was followed by a journey up the Mississippi, Barbary Coast offers abundant evidence that jazz had found a home in San Francisco in the 20th- century’s first decades even as the style was still coalescing out of ragtime, blues, and Afro-Cuban grooves.

But the closest and most essential companion to Harlem of the West is a book originally published in 1982 and reissued by the California Historical Society and Heyday Books in 1998, Tom Stoddard’s Jazz on the Barbary Coast. A seminal work that disrupted the myth that jazz’s birth in New Orleans was followed by a journey up the Mississippi, Barbary Coast offers abundant evidence that jazz had found a home in San Francisco in the 20th- century’s first decades even as the style was still coalescing out of ragtime, blues, and Afro-Cuban grooves.

Like Silva, Stoddard sought out any survivors who could provide first-hand accounts of the music and nightlife in the district now called North Beach. While civic reformers largely tamed the wide-open red-light district by the time Prohibition was adopted in 1920, it was the forum where protean Black music took shape in the Bay Area. The rapid decline of the Barbary Coast after decades as a roiling entertainment district offers another reminder about how the heavy hand of municipal policy can quickly remake a neighborhood. But it doesn’t take the enduring sting out of the demise of the Fillmore as the heart of Black San Francisco.

“You look at those photos and I just can’t wrap my head around it, seeing the vibrancy, the life that was in that community,” Silva said. “Sure, there were problems, but the stories in the Examiner and San Francisco Chronicle bandied around terms like ‘urban blight’ and ‘slums.’ The juxtaposition in what they were writing about goes against the photos taken by the people who lived and worked and played in the neighborhood. The powers that be couldn’t let the neighborhood be. It’s heartbreaking for all of the Bay Area to have lost this gem of a neighborhood. And for what?”