“Once you get over-the-hill, you really pick up some speed.” Quincy Jones has adopted that aphorism and spread it around — and it most certainly applies to Wadada Leo Smith, who is enjoying perhaps the most prolific Indian summer of any jazzman of any era.

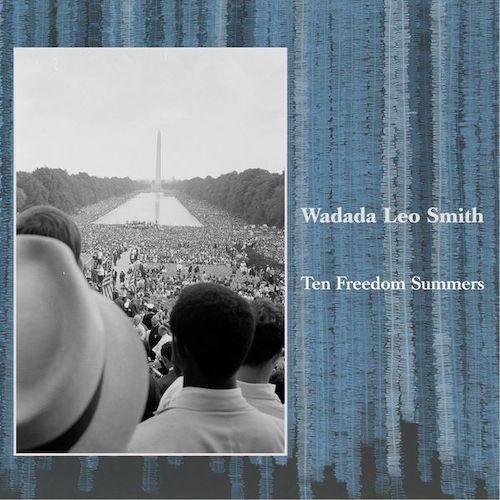

Although Smith’s work ethic looks pretty consistent over a long career that began in earnest in U.S. Army bands and first bloomed within the context of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), the staunchly forward-looking trumpeter, composer, theoretician, and educator’s current renaissance could be said to have begun with the 2011 performances and 2012 release of Ten Freedom Summers (Cuneiform). A massive collection of 19 compositions written over a period of 34 years and inspired by the civil rights movement, this 4 ½-hour series of reflections on several historical topics might be the longest sustained work ever composed by a jazz performer. For almost anyone in his 70s, it would be the culmination of a life’s work, but for Smith, it was just the opening of the valve to a flood of new compositions crossing back and forth through the porous membrane between the classical and jazz avant-garde.

And if that wasn’t enough, with his 80th birthday looming on Dec. 18, Smith — who became Wadada Leo Smith after a conversion to Rastafarianism in the 1980s — has moved into overdrive this year with a truckload of current and pending album releases. The Finnish label TUM, which is dishing out the gusher of new material from Smith, has already released a pair of three-CD boxed sets that provide heaping helpings of the trumpeter’s continued vigor and command of his instrument well beyond that of most who reach his stage in life.

Smith developed a theory of creating music that he calls “ahkreanvention,” in which any single sound or rhythm, or group of sounds and rhythms, is considered a single piece of music. In addition, each performer is a complete unit in himself or herself, operating independently of each other. If I’m reading this correctly, this sounds like the blueprint for free jazz performances — performers jamming together while simultaneously staying in their own worlds, creating an often furious froth of boiling sound that can be hugely invigorating with skilled musicians who listen to each other, or maddening if they wander off into endless self-indulgent effects without a context.

Smith never seems to get buried in the cauldron; his clear, forthright, open horn rides above the fray, or his muted horn muses thoughtfully, somehow simultaneously detached yet intensely involved. His strategic use of silence and his playing stance of pointing the bell of his horn toward the floor brings to mind another lonely figure — Miles Davis — whose playing Smith’s most resembles, but without the truculent attitude. Indeed, Smith’s crisply authentic 1998 exploration of Davis’s hard-core-funk “jungle band” repertoire circa 1972–1975 with guitarist Henry Kaiser on the album Yo Miles! (Shanachie) was one of the earliest acknowledgements of the prophetic value of that long-maligned stage of Davis’s evolution.

Sacred Ceremonies is the most immediately winning of the two new boxes, as it features Smith playing with and against two other masters of the outside — percussionist Milford Graves and the bassist/remix-master Bill Laswell. On disc one, Smith and Graves go at by themselves; disc two features Smith and Laswell, and disc three finds all three of them together.

Graves, who died of a heart ailment in February of this year, was a unique combination of drummer, percussionist, visual artist, sculptor, acupuncturist, martial artist, herbalist, inventor (with a stem-cell repair patent to his name), and teacher — all of which tied into his music in some fashion. Miles Davis allegedly wanted him in his band at one time, but he chose to go his own way. His drumming is a complex uninhibited combination of African, Latin, and jazz metrics, put forth with close-miked precision here.

The first part of “Nyoto” on disc one kicks off the session vigorously with Wadada playing against a pretty good groove, while “Baby Dodds in Congo Square” places the muted horn as a lonely voice musing over abstract polyrhythms, along with other passages for open horn and long percussion interludes. “Celebration Rhythms” is the toughest track to assimilate with its collection of extended techniques.

Smith plays in virtually the same way with Laswell on disc two, soaring above the clouds or sputtering at a lower level, yet the overall mood is darker, spacier, with the bassist offering a rounded tone with a sonic halo and subtle filigrees of electronics, always sparingly applied. The track titled “Tony Williams” has a muted repeated trumpet riff that is clearly as much a tribute to Miles (Williams’s onetime employer) as it is for Tony, and Laswell rumbles underneath with some digital delay and keyboard-like percussive playing.

Disc Three combines all three in the most invigorating set of the box, with Laswell’s smooth bass setting a groove and Graves’ polyrhythms splattering about underneath Smith’s self-contained bursts. “Truth In Expansion” begins with a digital delayed bass solo, then a trio jam, Wadada searching moodily, Graves battering on the toms, Laswell bubbling just above the surface. It sounds pretty free — and yet ultimately peaceful. I hear this record as a successor to Yo Miles! — if less dense, much sparer in texture, and not nearly as aggressive.

The second box, simply titled Trumpet, is a tightrope walk for Smith and a much more rigorous listen as it consists of three discs of just his solo trumpet exploring extended techniques of tonal production in a week of sessions in St. Mary’s Church in Pohja, a small town in Finland. Tribute pieces abound in this collection. “Albert Ayler” mythologizes in clarion calls the New Thing saxophonist who died under mysterious circumstances at the age of 34. In “Howard [McGhee] and Miles [Davis],” Smith snarls and sputters, the mute on and off, sometimes in mid-passage. “Sonic Night” is a moody muted meditation for bassist Reggie Workman. There are Black political heroes in the gallery, too. “Malik al-Shabazz” is, of course, Malcolm X as he was known in his last year following his Hajj to Mecca, feted in long muted tones squeezed soulfully out of the horn. “James Baldwin” features open horn and sounds more of a revolutionary battle cry, eventually sputtering, and recovering.

Yet by the time we get to disc three, the sessions have become a reprise of the techniques that we’ve heard before — and without any backing instruments, it frankly becomes rather tiresome. The Finnish church’s acoustics are pleasant, but nothing really special that plays a decisive role in the musicmaking like, say, flutist Paul Horn’s experiments inside the Taj Mahal and Great Pyramid do. The final track, “Trumpet,” is quietly fuzzy, distorted squalling, quite an ironic finishing touch and hardly a love song for the instrument.

Again, note that this is only the first batch of Smith’s 80th year recordings. Sep. 17 will see the release of a two-disc set, Chicago Symphonies, featuring Smith’s Great Lakes Quartet (with Henry Threadgill or Jonathan Haffner on saxophones, John Lindberg on double bass, and Jack DeJohnette on drums) and A Sonnet for Billie Holiday, with DeJohnette and an off-and-on collaborator, pianist Vijay Iyer, on a single disc. On Nov. 19, a seven-CD set — Smith’s biggest yet — containing his 12 string quartets as played by the RedKoral Quartet comes out, along with a four-disc set, Emerald Duets, with four different drummers (DeJohnette, Pheeroan akLaff, Han Bennink, and Andrew Cyrille. Wadada is picking up speed alright — and I hope that we can all keep up with him.