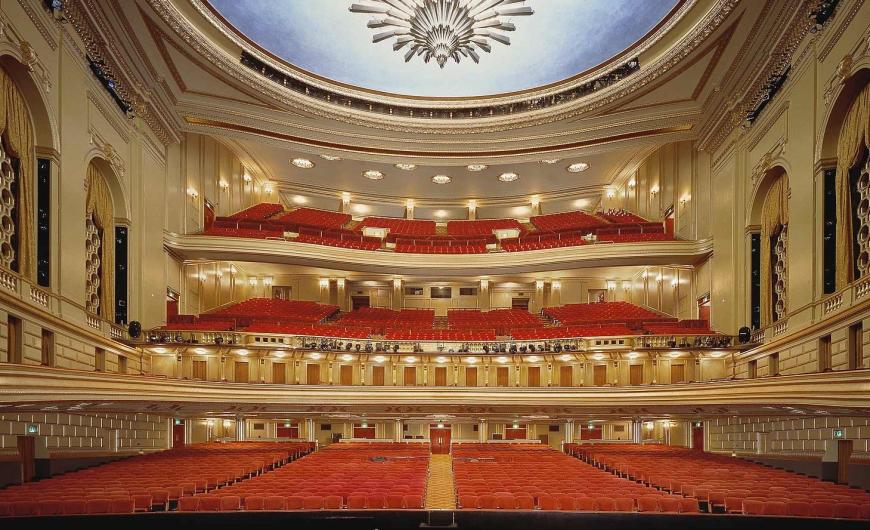

“The first time I set foot on the stage of the War Memorial Opera House, I fell in love,” says John Caldon. That was 13 years ago, when Caldon first started working here. In 2019, he was appointed managing director of the “landlord” San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center. It’s known as “SFWMPAC” for the sake of brevity, a bit less awkward than the name spelled out.

“The beauty of the buildings and the history of their cultural contributions to San Francisco can be felt in every corner of this place,” Caldon continues. “The War Memorial is the heartbeat of our performing arts community, and I can think of no better way to celebrate this milestone anniversary than by raising a glass in The Green Room and watching performances by the [San Francisco] Ballet, Opera, and Symphony.”

The raising of the glass is on Sunday, Oct. 23 at 4:30 p.m. in the Veterans Building’s Green Room, when speeches will greet the 90th birthday of the facility, along with performances from the three major resident organizations:

— Selections from Carmen and Rigoletto, performed by Laura Krumm and Christopher Oglesby of San Francisco Opera

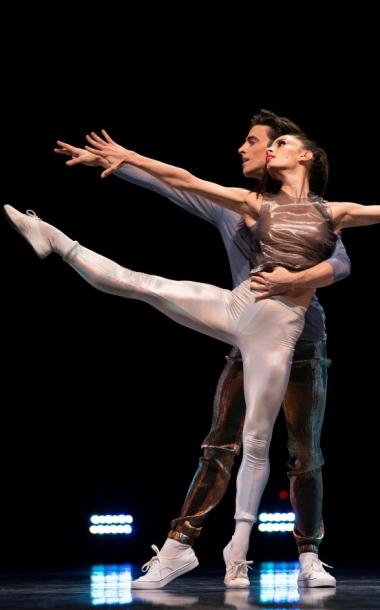

— The pas de deux from Justin Peck’s Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming, performed by Dores André and Esteban Hernández of San Francisco Ballet

— A movement from Mozart’s A Musical Joke, performed by musicians from the San Francisco Symphony (resident in the Opera House until the completion of Davies Symphony Hall in 1980)

The event is free and open to the public, but advance registration is recommended.

What exactly is the “SF War Memorial”? For opera fans (and others), it is the short form of the SF War Memorial Opera House. It can also refer to the complex of the Opera House and Veterans Building, both of which opened in 1932, substantiating the 90 candles.

But there is yet a third War Memorial, with various dates of origin. It is the above-mentioned SF War Memorial and Performing Arts Center, the umbrella organization, which includes, in addition to the Opera House and Veterans Building:

— Davies Symphony Hall, 1980

— Zellerbach Rehearsal Hall, 1980

— Herbst Theatre (originally Veterans Memorial Auditorium), 1932

— The Green Room, 1932

— The Wilsey Center: Atrium Theater and Education Studio, 2016

Adding in SF Civic Center neighbors — from the 1915 Civic Auditorium (now Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, under the management of Another Planet Entertainment) to the 1926 Panteges-built Orpheum Theatre to the 2021 SF Conservatory of Music Bowes Center — this is one of the country’s largest entertainment hubs, for an audience of well over 10,000. (Accommodating people, if not traffic and parking.)

Through the efforts of a small group of private citizens who brought a fundraising initiative to the community, the 1932 War Memorial became the first opera house in America built entirely through community donations.

Conceived as a memorial dedicated to the veterans and workers of World War I, it was designed by noted architect Arthur Brown Jr., who partnered with theater designer G. Albert Lansburgh. The Memorial Court between the two buildings was designed by Bay Area landscape architect Thomas Church.

The Veterans Building provided offices and meeting rooms for the San Francisco posts of the American Legion, as well as the galleries and offices for the original location of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. During seismic retrofitting of 2013–2015, the Veterans Building was reborn.

When SF Opera inaugurated the Depression-era miracle of the Opera House, there was an opening-night Tosca, followed by Lucia di Lammermoor with Lily Pons, one of the most popular divas of the time, in the title role.

Her second performance on Oct. 23, 1932, was broadcast live to the Civic Auditorium (the company’s former home and future temporary venue after the 1989 earthquake) and the Civic Center Plaza.

The city and the War Memorial dealt with the challenges of the Great Depression and World War II, neither halting music in the city, even when windows were blacked out in expectation of Japanese air raids. There followed financial downturns, the chaos of the $1 billion seismic upgrade project for the area, and then, the 6.9 magnitude Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989, which killed 63, injured 3,800, caused $6 billion in property damage, collapsed a freeway and several buildings, and damaged the War Memorial.

World Series or not, baseball had to wait, and the Bay Bridge and numerous freeways were down, but 72 hours after the quake, SF Opera schlepped across town and performed Otello in the Masonic Auditorium.

Aida followed the next day, on Oct. 21, and then Idomeneo, which was the scheduled show on the night of the quake. And then, led by General Director Lotfi Mansouri (who spent the quake’s 15 long seconds under his desk in his Opera House office), the company returned to the War Memorial on Oct. 24, performing Otello.

Somehow, SF Opera and audiences persisted in the damaged building for a time, with a net under the ceiling to catch falling debris — and then the two-year, $90 million reconstruction project closed the building (performances switching to the Civic Auditorium and Orpheum Theatre) before it reopened triumphantly on Sept. 6, 1997.

Nobody in the audience that night can forget the gala concert celebrating both the occasion and the 75th anniversary of the original War Memorial. Beverly Sills hosted the evening, Derek Jacobi was the master of ceremonies, and featured artists included Plácido Domingo, Marilyn Horne, and Frederica von Stade.

The moment to remember, as reported in The New York Times:

As the audience entered the auditorium, the house lights were dim, complicating the task of finding seats. But the reason soon became clear when Donald Runnicles, the company’s music director, commenced the evening by conducting the orchestra in the national anthem, the lights suddenly brightened with the line ‘‘And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’’ revealing, to oohs and aahs from around the house, the stunningly regilded interior with its repainted ceiling of aqua blue, flecked with clouds of white, and the glittering chandelier.”