Tysen Dauer writes for SFCV as part of the Emergent Writers Program offered in partnership with the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism. Look for an article from him every month.

You might expect boredom out of a performance titled Monotone - Silence Symphony. But 60-plus musicians and conductor Petr Kotik entranced a Thursday night audience at Grace Cathedral with the curiously dynamic sound of a single chord and then silence, each lasting 20 minutes.

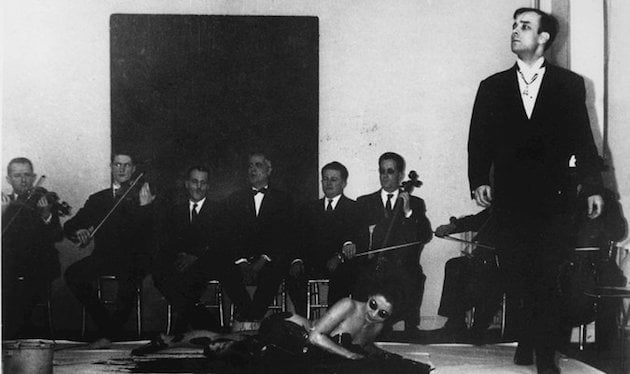

I first encountered Yves Klein’s Monotone - Silence Symphony at the Walker Art Center’s exhibit of his visual work. The score was hung on the wall like the famous, monochrome blue paintings next to it. Tall and narrow, the score consists entirely of a single chord played by instruments and sung by vocalists. Klein (1928-1962) divides the instrumental and vocal forces into groups that take turns sounding pitches to seamlessly sustain the chord.

This turn-taking is part of what makes the piece interesting and organic. Listening passively, the huge, bright mass of sound focused my attention on the changing elements. Now there was a reedy moment from the clarinet, now the brass stood out, now the high sopranos’ “Ah” drew me up … Listening more actively, any instrument I homed in on fluctuated ever so delicately in loudness or would eventually drop out, passing its note off to another performer.

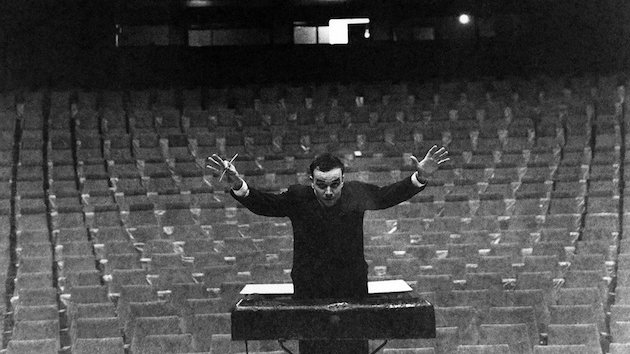

I’m not sure that sustaining the accurate tuning of a single chord between more than 60 performers for 20 minutes is humanly possible. At times, some of the notes “sagged” or dipped a little in pitch, resulting in stunning sounds. As the chord stretched out, more of these moments caught my ear and at one point the cathedral seemed full to the brim with something like the breathtaking sound of a full-throated, abandoned pipe organ. As Kotik raised his arms like Moses at the battle with the Amalekites to signal the end of the movement, the space pulsed with leftover sound waves.

But the captivating event was far from over. The second movement of Klein’s work consists of “silence.” He conceived the piece in the late 1940s (with the help of composer Éliane Radigue), around the time that American composer John Cage was thinking about how silence is so full of sound. Cage’s insight was at play on Thursday night: The sonic fabric of silence with interwoven sniffles, car horns, ringtones, shoe shuffles, pew creeks, and meditative oscillations stemming from Muni streetcars outside, rolled through the cathedral.

Funny as it sounds, the musicians performed the silence beautifully: At the close of the movement and the piece, the performers visibly relaxed their fixed positions and the applause began immediately. They had kept the audience on their wavelength for the entire piece.

At the start of the concert Kotik tried to prepare the audience for the experience. “We’re going to hear a piece of music…” Long pause. “…what can I say. It’s really not much different than other music but it sounds different.” This got some laughs from the audience but I think he was serious. It isn’t categorically different than other Western concert music: it has a fairly traditional, notated score, the single chord is familiar, there is a conductor, there are orchestral forces, it is made up of movements, and so on.

“…but it sounds different.” The piece, with all its traditional elements, acts differently than most concert music: It makes no structural demands on you (it does not reward a knowledge of sonata form); it offers no melodic earworms; it refuses to spotlight virtuosity. Instead, the piece invites you into its simplicity, allows you to enjoy the delightful and complex physicality of sound, and offers you a way of attending to silence. In light of this performance, the first on the West Coast, Yves Klein’s words make more sense: The Monotone - Silence Symphony, he wrote, is “what I wished my life to be.”