Stephen Sondheim’s musicals are all complex, rich, sophisticated, thought-provoking, and memorable — no wonder it took Broadway audiences decades to realize how much more valuable they are than singing cats and roller-skating trains.

But even against that background, the 1984 Sunday in the Park with George, now in a splendid production at the San Francisco Playhouse, is an especially demanding work. The way production director Bill English, Music Director Dave Dobrusky, and key cast members all meet the challenge is nothing short of sensational.

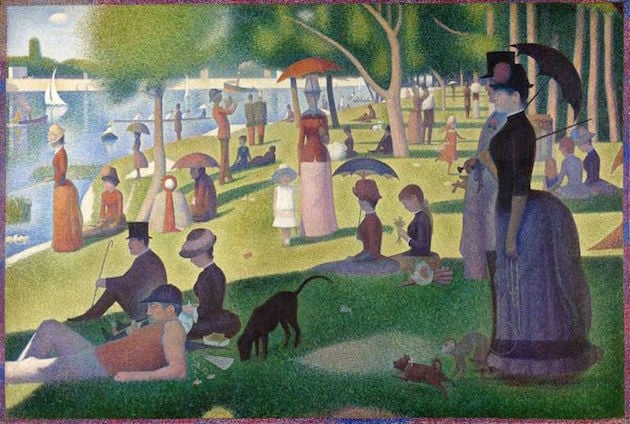

The work literally brings to life Georges Seurat’s 1884 painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, and pays homage to the painter’s dedication “to bring order to the whole through design, composition, tension, balance, light, and harmony.”

Sondheim represents Seurat’s pointillism — the neo-impressionist technique using tiny dots of colors that blend in the viewer's eyes into an image — with a percussive score that is akin to some of Benjamin Britten’s music.

Sondheim originally wanted to write “pointillist music” by assigning every white piano key a color on Seurat’s palette and “juxtaposing them the way he did in his painting, using the black keys to modify them the way Seurat used black and white,” according to James Lapine, who wrote the book for the musical and directed the Broadway production.

That idea didn’t work, but the complexity of the music Sondheim completed puzzled audiences and critics alike, getting mostly negative reviews, its premiere at the Booth Theatre running 604 performances (while Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats, debuting the previous Broadway season, ran over 7,000 performances).

But among critics, The New York Times’s Frank Rich gave the show a rave, writing that “Sondheim and Lapine demand that an audience radically change its whole way of looking at the Broadway musical.” Seeing an early, incomplete version of Sunday in the Park, Leonard Bernstein wrote to Sondheim that it was “brilliant, deeply conceived, canny, magisterial, and by far the most personal statement I’ve heard from you thus far.”

As Sunday in the Park is both a concept musical and poignant story-telling, the Playhouse production’s success depends on marshalling the company’s resources for the panoply of the spectacle while presenting a believable, affecting, evening-long duet by the principals (John Bambery and Nanci Zoppi).

Besides them, there are outstanding performances from the large cast, especially by Maureen McVerry as George’s mother. The invisible band of just six musicians sounds the equal of a Broadway orchestra: kudos to Dave Dobrusky and Ken Brill on keyboard, Lily Sevier (percussion), Audrey Jackson (reeds), Pamela Faw and Jason Totzke alternating on violin, Jonathan Betts and Margarite Waddell playing the demanding and exposed horn parts on alternate shows.

As George, John Bambery acts and sings with understated brilliance, bringing to life the pathbreaking painter, obsessed with his art, to the exclusion of meaningful relationships, neglecting and deeply hurting his model and lover, Dot.

Sondheim’s genius is in sketching out Seurat’s tragedy — he was 31 when he died, never having a major exhibit or selling a painting — without much narration or explanation. The lyrics in the songs Bambery performs powerfully reveal what’s important to him: “Color and Light,” “Finishing the Hat,” etc. Nanci Zoppi’s Dot sings of the two of them and their troubled, deteriorating relationship in the title song and in “Everybody Loves Louis.”

Zoppi’s performance is somewhat reminiscent of Bernadette Peters’s — comparisons are almost inevitable with the actress who created the role to great acclaim — but in Zoppi’s singing and stage presence, there is an inimitable individuality, as she formulates Dot on her own terms, not playing the character but becoming her.

Bambery and Zoppi continue to excel in the second act, which moves the story a hundred years to the future (actually to the present of the musical’s Broadway premiere), the two becoming their own great-grandson and his grandmother, respectively. George and Dot are reunited in this strange fashion, bringing art and life together with a determined call to “move on” —

Stop worrying where you’re going —

Move on.

If you can know where you're going,

You've gone.

Just keep moving on.

I chose, and my world was shaken —

So what?

The choice may have been mistaken,

The choosing was not.

You have to move on.