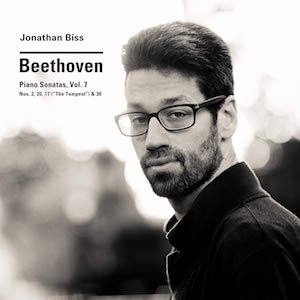

In one sense, it was like arriving for a movie an hour late or starting to read a novel two-thirds of the way in. How much had a listener missed by only catching up to Jonathan Biss’s cycle of the complete Beethoven piano sonatas at the fifth of his planned seven Cal Performances recitals at Hertz Hall?

The short answer is 18 of the composer’s 32 works in the form. But as the Dec. 15 performance affirmed, an afternoon of any five Beethoven sonatas is bound to contain multitudes and feel complete and satisfying in its own right, irrespective of what had come before and what remains.

That’s especially true when the author of this heroic undertaking is Biss, a pianist whose probing, incisive, and deeply considered performances are consistently challenging and rewarding. And so it was on Sunday, when the artist took on a varied slate of works both early (Sonata No. 11) and late (the magnificently form-bending Sonata No. 30), familiar (Sonata No. 14, “Moonlight”) and undervalued (Sonata No. 24, “À Thérèse”). Sonata No. 25, (“Cuckoo”) filled out the program.

Mounted in celebration of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, the Biss Beethoven cycle began in September. The pianist has also been recording the sonatas over a nine-year span. The Berkeley cycle performances conclude on March 7 and 8, 2020.

While there was plenty to relish at concert five, two pieces stood out — the eventful and evocative Sonata No. 11 and a delightfully fresh and engaging account of Sonata No. 24.

For this listener, the earlier of the two was particularly gratifying. From the opening Allegro, Biss took on this handsomely sprawling work as if to persuade an audience of its merits. He succeeded and then some.

Marked by decisive runs and trills, taut rhythms, and dramatic tremolos, this B-flat major work began and developed in a decisive, declamatory mode. The chords were full throated, the passagework at once fleet and consequential. A mysterious mood descended briefly near the movement’s end.

What followed was equally fine. The spacious Adagio opened out with harmonic and contrapuntal amplitude. The Menuetto paired playful wit — not always a Biss strong suit — with a sense of storm clouds gathering and then unloading in the turbulent middle section. Strumming arpeggios and pattering runs brightened the closing Rondo, which also turned foreboding. A clipped, fugue-like figure was both alarming and liberating, yet another arresting turn of this densely plotted work. Biss burrowed in and tracked it all.

Sonata No. 25, dedicated to a Beethoven piano student, Countess Thérèse von Brunsvik, opened the second half of the program with another show of distinction. Biss, who can infuse the smallest passage with meaning, did so with his poignant expression of a brief Adagio opening. Then it was on to a bracingly clear-eyed account of related and new material. The development section was especially notable, full of suspense and surprise.

Beethoven the dramatist emerged throughout, in dynamic swerves, jaunty accidentals, one strangely harmonized haze, and propulsive bursts. If matters got a little chaotic here and there — Biss can go in for blistering tempos — a certain unruliness is not an alien notion in Beethoven.

The recital began in a supersonic blur, with the cross-handed niceties of the Sonata No. 25 Presto lost in the sprint. An autumnal, last waltz air came as a welcome interlude in the middle movement.

Lovely, too, was the “Moonlight” Adagio, known to piano students far and wide. Biss didn’t try to bend or repurpose in any way; a soft flowing liquidity prevailed. The wild-ride final movement was exciting if a shade reckless about the details.

The afternoon came to a close with the intimate and deeply felt variations in Sonata No. 30. Biss murmured the theme with aching understatement, then submitted it to a series of passionate trials, by turns percussive and gentle, remorseless (the fugato) and resigned. Never mind that he lost his way and dropped a phrase at one point. Perfection is never the goal.

In an hour and a half of intense music-making, Biss answered Beethoven’s summons to be fully present for the sweetness and pain, the weirdness and wonder of a sonata cycle that keeps on spinning out new ways of apprehending it.