Cuba and Puerto Rico share fecund musical roots. Caribbean islands populated by a mixture of indigenous natives and African slaves as well as Spanish and American colonizers, their cultural heritage is rich and complex. Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra likes to recall that as a boy he often saw the great Spanish cellist Pablo Casals play Bach and Beethoven on the local television station while the first salsa recordings of the Fania All-Stars blared outside on the street. Sierra, who studied composition as a young man with György Ligeti, has become one of the world’s most acclaimed contemporary composers by artfully honoring his diverse roots.

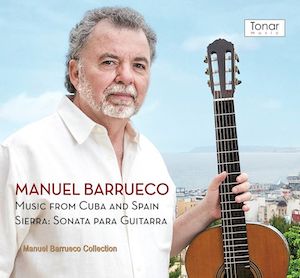

The Cuban guitarist Manuel Barrueco came to the United States as a teenager when his family fled the Castro regime. A short time later he won a lasting place on international stages with his meticulous and highly expressive arrangements of piano music by Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados. Barrueco’s new recording, Music from Cuba and Spain, Sierra: Sonata para Guitarra (Tonar), includes Spanish music of the Renaissance and Romantic eras, five Danzas Cubanas by Ignacio Cervantes, and, most notably, a new work dedicated to Barrueco, Roberto Sierra’s Sonata para Guitarra. Barrueco has had a long and fruitful relationship with Sierra and is the ideal interpreter.

The Cuban guitarist Manuel Barrueco came to the United States as a teenager when his family fled the Castro regime. A short time later he won a lasting place on international stages with his meticulous and highly expressive arrangements of piano music by Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados. Barrueco’s new recording, Music from Cuba and Spain, Sierra: Sonata para Guitarra (Tonar), includes Spanish music of the Renaissance and Romantic eras, five Danzas Cubanas by Ignacio Cervantes, and, most notably, a new work dedicated to Barrueco, Roberto Sierra’s Sonata para Guitarra. Barrueco has had a long and fruitful relationship with Sierra and is the ideal interpreter.

The thorny, four-movement sonata is a major addition to the guitar repertory, as serious and impassioned as the Violin Sonata of Béla Bartók. The work begins “Con pasión,” exploring asymmetrical rhythms of five and three contrasted with slower and more introspective music. “Expressive, casi religioso,” the second movement, contrasts reflective, religious counterpoint with increasingly intense interruptions. The “Scherzando” is a wild dialogue between quiet rhythmic figures and free improvisatory passages. The concluding “Salseado” uses rhythmic figures Sierra first heard as a boy from the Fania All-Stars.

Also outstanding, though very different in effect, are the five Danzas Cubanas by Ignacio Cervantes, one of the most important Cuban composers of the 19th century. Forced into exile in the United States in the 1890s, Cervantes gave concerts to help fund Cuba’s war of independence from Spain. His elegant, refined, and charming melodies show no trace of this drama. The music has a whimsical air and Barrueco plays this music of his youth with a palpable love.

The Spanish pieces on the disc include Castilla (Seguidillas) and Aragón (Fantasía) by Isaac Albéniz, and Andaluza (Playera) by Enrique Granados. This is music with which Barrueco made his reputation as a young man and his subsequent experiences have only deepened his interpretations. Several composers of light music make for a well-rounded program. Sebastián Iradier, best known as the composer of the tune Bizet borrowed for the famous habanera in Carmen, is represented by his popular La Paloma. Joaquín Malats, the pianist Albéniz chose to premiere his Iberia, is represented by his La Morena.

Newer to me are Barrueco’s crystal-clear performances of music by the Spanish Renaissance composer Luis de Narváez as well as a related modern work. Making a connection between the Renaissance and the 20th century, Joaquín Nin-Culmell’s Seis Variaciones sobre un Tema de Milan uses a pavane by the Spanish Renaissance composer Luis Milan as the theme for a set of variations in a neoclassical style with a strong Spanish undercurrent.

Manuel Barrueco’s deep connection with the music on this disc and the cultural heritage it represents make this a highly recommended recording.