Silenced for so long by the pandemic, live music, for this listener at least, is still something of a wonderment. Even as concert schedules have filled out over the passing months, drawing audiences in often gratifyingly large numbers, a certain sense of strange newness remains. What a marvel it seems, afresh, that a hundred or several thousand people can come together to remain largely silent in each others’ presence in order to feel closer to their companions and fellow strangers through what they are all hearing and seeing together in the moment.

An April 9 lieder recital by the celebrated baritone Matthias Goerne, presented by San Francisco Performances at Herbst Theatre, set such musings in motion. Midway through an opening set of eight songs by Hans Pfitzner, a kind of split-screen effect took hold. As Goerne swayed, crouched, and gestured into a full-body immersion in the music, from head voice pianissimos to booming fortissimos from the chest, faces up and down the Herbst rows were fixed on the printed texts in the program.

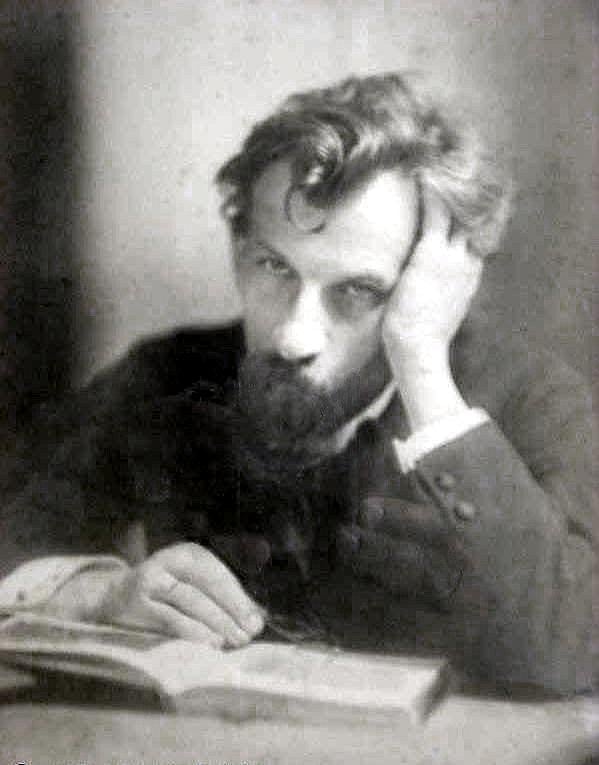

Pfitzner (1869–1949), a German composer presumably not well known to many if not most in the house — the opera Palestrina is his most salient credit — apparently demanded close attention to the poem texts he set. I followed suit for a while, toggling back and forth from the German lines by Heinrich Heine, John Audelay, Richard Volkmann, and others to the facing English translations.

Such close listener “readings” can certainly pay dividends. When Goerne reached the line rendered in Stewart Spencer’s English as “Come, O universal night” in Friedrich Lienhard’s “Abendrot” (Sunset), the plea felt summoned up from fathomless, yearning depths. Accompanist Seong-Jin Cho brought a mighty urgency and force to the ringing chords at that song’s end.

A different kind of bold-faced singing arrived in Karl Benedikt’s “Nachts” (At night), as Goerne reached the resonant, near ecstatic heights of sacred witnessing: “Our Lord is passing above these peaks and blessing the silent land.” This time, the pianist added a simple benediction of two notes dying into silence. Elsewhere, Cho occasionally overindulged in slow tempos.

Trying to focus carefully on the texts and not lose the spontaneous presence of the performance can be, well, trying. Goerne tacitly confirmed that fact by waiting, with what registered as thinly veiled impatience, whenever the audience shuffled through a page turn. This is live music, he might have been reminding us, not an art song classroom.

I began shifting my own attention gears, at some points hewing keenly to the text and at others focusing solely on Goerne in voice and body. Yet even the latter choice had its complications. Positioned behind a music stand, where he remained throughout the 90-minute, intermission-free evening — which included the Wagner Wesendonck-Lieder, a repertory staple, and five well-known songs by Strauss — he seemed slightly removed and remote. Even his gestures, which featured a downward, carving motion of one hand, began to seem redundant. Goerne’s stony facial expression rarely varied.

His singing loosened and warmed up some when he reached the Wagner. In “Engel” (The angel) he found the tender astonishment of a child’s apprehension of the divine. After Cho lingered over the composer’s choice harmonies, Goerne made the trees and sunlight of “Im Treibhaus (In the hothouse)” shimmer to life with a lithe timbre. And yet a certain sameness to the singing persisted. Big bursts of sound detonated with impressive if somewhat numbing impact. Softer passages occasionally felt routine and shapeless.

The best came last, in the Strauss songs. “Traum durch die Dämmerung” (Dream in the dusk) took on a hushed astonishment. The rhapsodically simple “Morgen!” (Tomorrow) was beautifully understated. “Ruhe, meine Seele!” (Rest, my soul) had a fervent forward motion, faultlessly phrased.

There was one encore — Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Bist du bei mir” (If you’re with me). Hands folded at his chest, Goerne delivered the Baroque beauty with a sweet yet focused restraint. He might have been offering this parting number as a kind of prayer, a wish for us all to stay safe and stay connected.