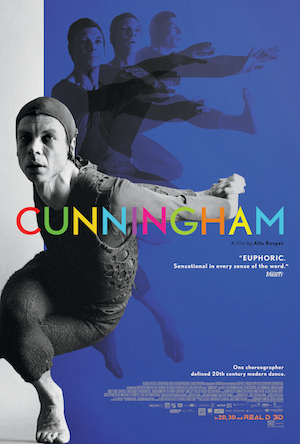

Cunningham (in 2D), Alla Kovgan’s documentary debuting this week at the Embarcadero Center Cinema, is a movie I wish had been around when I was a new dance writer. There have been other films touching on the art of Merce Cunningham, but none that so approachably and so beautifully, via archival studio footage and performance, captures what the iconic choreographer, who died in 2009 at the age of 90, meant to dance, as well as what he meant. “We don’t interpret, we present,” he explained, or, as I believed early on, didn’t explain.

We see excerpts of his work dating between 1942 and 1972 and hear from some of the original creators and dancers, including Carolyn Black, Cunningham’s first dance partner, Gus Solomons Jr., and Valda Setterfield, as well as later company members and dancers from other troupes trained in Cunningham technique.

Those composers and designers whose work is in the film were connected to Cunningham’s dances, but not exactly collaborators, because music and décor were always created separately from his choreography, not to unite until the dance premiered. They include composers John Cage and David Tudor, and artists Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol.

John Cage was part of Cunningham’s artistic and personal life from his beginnings as a dance student in Seattle, when Cage was his composition teacher, until his death in 1992. Their interests in eastern philosophy linked with their artistry and inspired each other. Cage came along on the company’s early tours via VW Microbus, even foraging mushrooms for the dancers’ meals as an expert mycologist. We see excerpts of notes, personal yet discreet (Cunningham sometimes speaks of “Mr. Cage”). One note asks, “When are we going to be together?” A comment from Cunningham, which could apply to many things: “I have nothing to say, and I am saying it.”

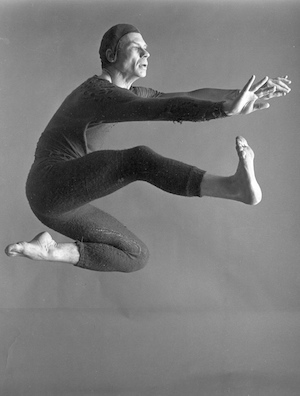

And showed it. Cunningham protested that he hated dealing with the costumes and the music of performance. But obviously from the look on his face and the alertness in his form, he loved to perform; he had a face and of course, particularly because it was his instrument, a body meant to be seen, even as it matured and aged. The film is worth what? A thousand words at least.

When Cunningham had nothing to say, he said plenty; some of his greatest hits are here, a catalog of favorites like Antic Meet, Rainforest (with Warhol’s floating silver Mylar pillows), Summer Space, with Jasper Johns’s dappled camouflage leotards, and Morton Feldman’s music; 1964’s dangerous, foreboding Winterbranch, the dancers in the dark atop a city building as sounds rush by. It would have been nice if specifics of each dance — title, company, composer, designer — popped up onscreen, but perhaps it would have interfered with the beauty of dances and dancers.

The movie confirmed two suspicions. First, that Cunningham sometimes did intend to convey a mood or a message. He replied that he just put it out there and audiences could take whatever they wanted from it. It’s reminiscent about the old joke about a psychiatrist’s patient taking a Rorschach test. Every inkblot reminds him of sex. The psychiatrist asks, how can each one remind you of sex? “Well, doc,’’ replies the patient, “you drew the dirty pictures!”

And then there’s suspicion number two: Despite Cunningham’s close hold on his thoughts and emotions in his choreography, in which, for instance, it’s rare for partners to come face-to-face with each other, depersonalizing the quality of the movement and the interaction, many of his works embody powerful emotion.

I first noticed his sense of removal, of a wish for privacy, in the 1980s on a weekend trip with the company to Wellesley College. Cunningham sat down on the bus, took note of the presence of a reporter and photographer from Newsday, and unfolded the day’s New York Times in front of him. It was very funny, but he wasn’t laughing.

But later, as he danced a duet with one of the women during the performance, their close partnering, rarely face to face, their exquisite juxtaposition to each other and to other dancers, spoke of more than craft. There was something else palpably on the stage, and maybe Cunningham would have said that people could make of it what they would. I called it love.

Speaking of which, it would be nigh-impossible not to fall in love with the gorgeousness of these dancers. Having been blessed with great tickets over the years, I still found it a real treat to get front-row or wing-side views from the film. And a long excerpt from a daytime concert in the courtyard of the Louvre was particularly stunning, with two groups of dancers in full costume giving their all for a group of tourists — views near and far, perhaps via camera crane, exposing the company’s concentration and perfection even for a casual show.

Cunningham said that when he died he wanted the company to end, but he also set in motion the Merce Cunningham Trust, which licenses and supervises the repertory the world over. As persuasively as those costumes in Summerspace, the landscape of modern dance is dotted with performers carrying on his work. There will always be room in the world of dance for Cunningham’s genius and, if films like this continue to be made and seen, endless inspiration.