Bare feet and bassoons, a subversive symphony, a redwood-bark-wrapped drum as tall as a cherry tree, and a woman with a voice as pure as fresh rainwater produced mixed results at Oakland Symphony’s Feb. 24 concert.

“Notes from Native America” brought long overdue attention to music made by indigenous Native American populations. Included in the program were two sections from Chickasaw composer Jerod Impchchaachaaha’ Tate’s Lowak Shoppala (Fire and Light), an appearance by SuNuNu Shinal dancers from Kashia Stewart’s Point Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, and Big Sur: The Night Sun, a four-movement work with text consisting of Ohlone themes written and composed by African-American composer John Christopher Wineglass.

Morgan cast Shostakovich’s perky, upbeat Symphony No. 9, which opened the performance, as a backhanded “poke-in-the-eye” at Stalin, who expected the Russian composer to create a supremely grand, moody, war epic. Likening Stalin to President Donald Trump, Morgan suggested that an artists’ role in society is, in part, to enlist in “works of resistance” against dictatorial and exclusionary political leaders, earning, perhaps, the night’s most spontaneous applause.

Shostakovich’s Disney-like symphony was delivered with aplomb. The Ninth Symphony lacks the cohesiveness of its predecessor, offering mostly showy dexterity for the brass and woodwinds in the Allegro opening and Allegretto and but a few seductive, enticing conversations between clarinet, flute, and strings in the Moderato movement. The dark, thematic snippets found throughout the work barely approach the macabre, mesmerizing power of his Eighth Symphony. The faults were not in the performers — principal bassoonist Deborah Kramer’s brief, spellbinding solo seemed to stop time — but in the work itself. Which led to the question: Is the most significant art created when an internal, less-didactic response is at its source?

The answer, in one form, came in the evening’s finest music, Wineglass’s Big Sur. The work grew out of the composer’s residency at Glen Deven Ranch, and from contributions from youths at a music camp; poet Robinson Jeffers’ essays about the California coast; and contemplation of the Pacific Ocean.

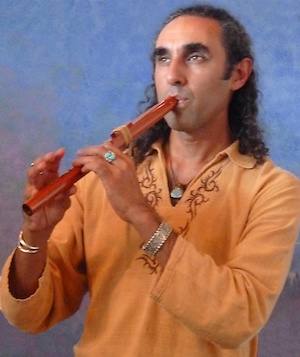

The first and last of four movements were the most compelling. Percussionists Marcie Chapa and Jayson Fann launched Big Sur with a too-short exchange from atop loft-like perches on either side of the stage. When the native flute, played by Emiliano Campobello, and singer Kanyon Sayers-Roods’s sparkling voice entered the mix, it was in some sense too soon, but instantly rewarding. With the big textures and oomph of a full orchestra, there’s some satisfaction that a few pieces of wood and cloth, enough oxygen, and the human body are able to create transcendent music.

Of course, Wineglass made good use of the orchestra in the work’s middle sections. Plush lines for the cellos provided a pillowy bed; Hadley McCarroll’s brief, tender piano solo joined by flutist Alice Lenaghan cast a spell; gorgeous “singable” harmonies emerged but never lingered overlong. Even so, Sayers-Roods’s astonishing “bird calls” and fluid delivery in the outer movements were most thrilling.

Feather Dances was less successful. Performed in a too-small space and ineffectively lit — the general, overall lighting also emphasized the waiting, fidgety orchestra — the dancers were reduced to compacted lines and tight-circling patterns. In comparison with Native American dances I’ve seen on the shores of Lake Michigan or in a vast, native grass- and wildflower-covered field in Minnesota this was awkward and disappointing.

Tate’s Hymn and Clans were narrated by Vincent Medina supported by the orchestra and male members of the Oakland Symphony Chorus. Medina appeared nervous — darting glances at Morgan, breathing inconsistently, and sometimes inaudible or sounding out of breath — which was a distraction from the text’s rich, poetic content.

The work’s strengths were in imaginative instrumentation: aggressive percussion and brass for a “raccoon” section, lovely lyricism for “skunk.” Tate’s work reminds a person that a drum can “speak” and violins “hum.” Despite these charms, solemnity bordering on melodrama prevailed during sections titled “Chief” and the strong parts failed to galvanize the whole. Perhaps the entire eight-section work would make a stronger, more satisfying overall impression. Regardless, it left a taste for future collaborations and Morgan assured his audience that he was “not done helping the story [of Native American music] to be better told.”