Today, we mostly hear instrumental music from the Baroque period as transcriptions, because musical instruments — particularly keyboards — have evolved much in the last three centuries. Many works written for harpsichords and clavichords are now frequently performed on iron-framed pianos with little resemblance to the sound of the period instruments. Pipe organs today are perhaps are the keyboard instruments closest to those in the 18th century, but they are rarely heard outside churches.

It’s not much of a surprise, then, that organ music is sometimes transcribed for piano.

Ferruccio Busoni, over a period of 30 years, published volumes of J.S. Bach’s keyboard works, primarily consisting of piano transcriptions of organ works, and even works for other instruments. In order to cover a greater range of pipe-organ music, Busoni asked piano manufacturers to add more notes in the bass range.

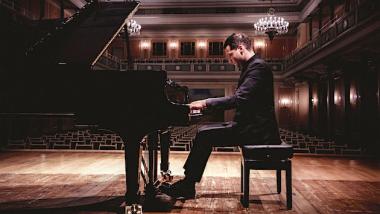

A survey of transcriptions of Bach’s organ works by Busoni was the focus of the first half of the recital by Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi at Herbst Theatre. Piemontesi began radiantly with the Prelude in E-flat Major, BWV 552, and engulfed the hall with colorful sonorities. He created the illusion of being in a cathedral with the sound echoing from all directions.

Piemontesi had an uncanny sensitivity to tonal balance, and seemed to assign different tonal characters to different lines by carefully balancing octave unisons to control the harmonics, and laying out distinct voices with different touches. While this would simply be accomplished by using the different manuals on an organ, it is another matter to accomplish the same on a piano.

Piemontesi continued on with the solemn Nun komm der Heiden Heiland (Now come, savior of the heathens) BWV 659, and the Cantata No.140: Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme (Awake, the voice is calling us), and clearly laid-out voices continued. In the Cantata though, the pianissimo was was exquisitely controlled, with not a single note out of line: It created the effect of music being played on multiple instruments.

It appeared that Piemontesi was attempting to assemble a larger suite by inserting additional works between the Prelude and Fugue, BWV 552, but it was somewhat puzzling to hear the “Italian Concerto,” BWV 971 — still a transcription, as it was never composed for a modern piano. Here, Piemontesi imitated the quality of harpsichords through crisp articulation of each note while continuing to give distinct colors and characters to the separate voices, as it would be heard on a harpsichord. The ebullient third movement in particular was delivered with inspired ornamentations.

Siciliano, from Bach’s Flute Sonata in E-flat Major, BWV 1031, transcribed by Wilhelm Kempff, provided a quiet interlude before jumping back on to BWV 552, concluding the first half of the program with a full, engulfing reading of the Fugue. Explosive with vibrant colors, Piemontesi’s interpretation again surrounded the audience with sound.

The second half of the program leaped over the 19th century entirely, and Piemontesi continued to employ his disciplined control in two works from the early 20th century. In the tonally ambiguous, primarily whole-tone “Cloches a travers les feuilles” (Bells through the leaves) from Debussy’s Images II, the distant bells sparkled with a piercing tone. The heavily perfumed “Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut” (And the moon descends on the temple that was) alluded to the ruined temples in southeast Asia, while “Poissons d’or” (Goldfish) brightly illustrated the capricious movement of koi in a pond, as inspired by Japanese lacquerware.

Piemontesi concluded the concert with the rarely heard first version of the Rachmaninoff Sonata No. 2. Originally written in 1913, the version we most often hear is the revised version from 1931. The revision took away elements the composer described as “superfluous,” and simplified the parts where “many voices are moving simultaneously.”

As if to “pull out all the stops,” Piemontesi exploded into the valiant opening, then dug deeper. Employing his deliberate control of tonal colors assigned to multiple voices, his effort helped bring out details from the densely written score. The dynamic contrast between the roaring first theme to the pensive second theme was sobering. The second movement, which was largely left untouched, provided a respite with rich lyricism. The dense third movement revealed why the composer pared it down. Despite Piemontesi’s efforts, some parts of the score only added gluttony, while the simpler structure added clarity.

As an encore, Piemontesi offered an intimate yet playful reading of Handel’s Minuet in G Minor, HWV 434, in its original form, rather than the more frequently heard arrangement by Kempff.