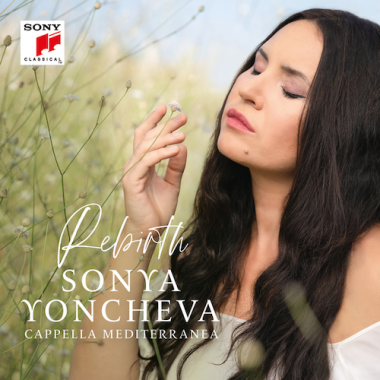

Rebirth? What a puzzling title for a recital from Metropolitan Opera soprano Sonya Yoncheva and Leonardo García Alarcón’s Cappella Mediterranea, which is a grab-bag mix of Baroque laments and personal favorites.

Yoncheva claims lofty goals for a project “of great personal and artistic importance to me.” She writes in the liner notes to Rebirth, “I would like to highlight the timeless quality of this [Baroque] music, the sense of unlimited freedom that it offers us human beings in such an instantaneous way. For me, it is an appeal for a rebirth, for the renewal of the kind that our world so desperately needs today.”

These are lovely thoughts and noble aspirations for an album timed to emerge from the silence of a deadly global pandemic to introduce listeners to the “contemporary message” of Baroque music. But just how hopeful and contemporary is a recording whose first vocal selection, Stradella’s “Those tears and sighs,” is followed by no fewer than 11 other selections that are mostly slow laments? Even though the poetry of these laments often invoked “death” as code for orgasm — this is certainly the case with John Dowland’s rather explicit “Come again, sweet love now doth invite” — many of this album’s laments address death and suffering of a more final sort. With opening lines as heartening as “These tears and sighs,” “The tomb opens, I announce my death to you,” and “I take pleasure only in weeping,” I cannot help but wonder about the nature of the renewal that Yoncheva and Alarcón attempt to offer.

Yoncheva extends the album’s reach to includes a Bulgarian folk song, several mostly upbeat Baroque instrumentals, and (take a deep breath) 6 minutes and 20 seconds of ABBA’s “Like an Angel Passing Through My Room.” Best, then, to accept it as personal and idiosyncratic, and focus instead on the singing and musicianship.

Although it’s impossible to ignore Yoncheva’s diva-like approach to simple fare, the voice itself is a thing of great beauty. Whether it has grown meatier and breathier in the lower range since 2007, when the then 26-year-old participated in William Christie’s “Jardin des Voix” academy for young singers, I do not know. But on a recording that is heavily engineered to help realize Alarcón’s goal of transforming the sounds of instruments “in a way that would allow our accompanying voices to create an aura for the soloist,” Yoncheva’s easily produced upper range glows with a rare and paradoxically weighty radiance. With minimal if any vibrato, it soars on high with a luminous warmth and ease that helps explain why she won the 2010 Operalia competition and became one of the Met’s biggest stars three years later. If only she didn’t sound so muffled, and so many consonants weren’t swallowed.

Some of Yoncheva and Alarcon’s interpretations will be controversial. Take, for example, their interpretation of the Dowland. I auditioned at least 16 other versions from Brian Asawa to Sting to Emma Kirkby. (Kirkby’s late career live performance is very different from her earlier commercial recording). All are unique but none tries to contemporize Dowland’s music by slowing down so radically in one verse, adding a bridge, and repeating the final lines like a pop ballad. Nor does any other version quite sound like an artist trying to aspire to what she is not. After all, some of Yoncheva’s recent roles have included Mimì, Tosca, Imogene in Il pirata, Cherubini’s Medée, Verdi’s Violetta, and Giordano’s Fedora. If that career path isn’t the mark of someone determined to define herself as a soprano assoluta in the tradition of Callas and Olivero, I don’t know what is. In jumping from grand opera to Dowland and ABBA, Yoncheva too often sounds like a diva who attempts to hide her Tiffany jewels in her Gucci bag as she runs barefoot through fields of flowers.

Which is not to deny the beauty and value of many of the selections. Emotions are intense in Francesco Cavalli’s “Ed è pur vero, o core … Luci mie, voi che miraste” from Xerse, and equally vivid in Yoncheva’s wonderful albeit grand performance of Barbara Strozzi’s “L’Eraclito amorosa.” Cappella Mediterranea’s instrumentals, which provide variety amid the many slow laments, are consistently colorful, beautifully performed, and far better recorded than Yoncheva’s voice. But Lord almighty, if Yoncheva’s recitation in the middle of Alfonso Ferrabosco’s “Hear me, O God” doesn’t became a camp party favorite, there’s no accounting for what this world has come to.