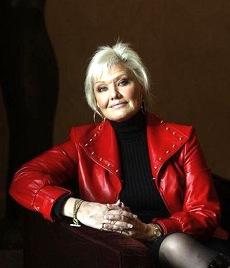

Meeting face-to-face after an intense, six-hour rehearsal at San Francisco Opera for her role debut as Emilia Marty in Leoš Janáček’s The Makropulos Case, soprano Karita Mattila no doubt would have preferred to luxuriate in a bubble bath. Nonetheless, the great singer-actress, who recently showed her all onstage in Salome, slowly revealed herself. Speaking in the opera house that has also hosted her role debuts as Katerina in Kat’a Kabanova (2002) and Elsa in Lohengrin (1996), and that welcomed her Ilia in Idomeneo (1989), Eva in Die Meistersinger (1993), and the title role in Manon Lescaut (2006), the diva who turned to her Live From the Met audience before taking the stage and declared, “Let’s go kick some ass!” shared thoughts on her imminent debut, ill-prepared conductors, and life at 50.

Here you are in your role debut. I was just reflecting on how some singers sound on opening night, and in subsequent performances. Sometimes it’s like night and day. What is opening night like for you, especially in a new role?

[Exhaling deeply]. What an introduction!

Opening night, of course, is a very special night. It’s the first time you do it. It’s an exciting night. I assume that in this case, having a very long rehearsal period of four weeks, we will be well-prepared. The better you are prepared, the more secure you feel.

How did this debut come about?

It was David Gockley’s first request. At the opening night of Manon Lescaut, he asked what I would be interested in doing. I suggested that I would love to do Makropulos Case for the first time. He immediately got excited about that, and here we are.

What is it like for you to play a 300-year-old woman?

Well, I don’t know yet. I tend to be very careful, before I’ve done the role, to explain too much about it, because it’s still in the process.

What I can say now is that it’s a fascinating and wonderful part. It’s totally ... I wouldn’t say crazy, but it’s so many different things, this story, and different from the play. But it’s a very fascinating personality, totally crazy like a fairytale character. A wonderful, wonderful acting part, of course, because it has all kinds of possibilities that you wouldn’t have with characters that lead a normal life.

Are you discovering, as you rehearse, that she is emerging in ways you didn’t initially expect?

Oh, sure. I didn’t expect much of anything regarding the production because I have never seen this live or on video. When I actually started working on this, I decided that I wasn’t going to watch any video. I wanted to prepare it with good coaches, and then just see what I do, because I totally trusted this team we have here.

To have a conductor present at the rehearsals is wonderful, of course. I know conductor Jiří Bĕlohlávek and director Olivier Tambosi. They are absolutely wonderful in what they do. I feel I am in safe hands.

The better the performance is directed, the more freedom it gives, so every performance can be different. You never lose, of course, the professionalism, or break the frame of the basic ideas of the director. But if you are totally aware of who you are and why you are here and what you are saying and what is happening, it gives you a certain safety and security onstage. I have always felt that my best performances have always been in the strongest productions, mostly with directors that are remarkable.

Take Luc Bondy’s Tosca. That, for sure, was a wonderful experience. [In] the best productions, you also feel at your most free. You don’t separate singing from what you’re doing onstage. A lot of directors aim to that, but they don’t always succeed. It also takes the willingness of the singers to work on it.

I’m, of course, immensely grateful for David [Gockley]. When the recession hit, I thought this opera would be the first to go.

But I’ve seen it before here. It’s a fabulous opera.

Yes, yes, we know that. But people who don’t know it would think it wouldn’t sell well because it’s a strange name and nobody knows it and blah blah blah. And we are here. Bravo, David! What else can I say? I’m a big fan of San Francisco Opera.

When I told my editor at American Record Guide that I was going to interview you, he said that he saw a broadcast where you turned to the camera and said something like, “Okay, now we’re going to kick some ass.” My editor said, “That’s my kinda soprano.”

[Chuckling a bit to herself] Ha-ha.

Featured Video

Karita Mattila & Thomas Hampson:

"Vilja" & "Lippen schweigen" (The Merry Widow)

I remember a broadcast where you did a duet from The Merry Widow with Thomas Hampson. If a woman could ever convince a man to commit infidelity on national television, it was you. You were fabulous.

Thank you.

You were so seductive. I was screaming and applauding as I watched.

Well, The Merry Widow is a wonderful piece, a wonderful part. You get to laugh, not die at the end, and you get the man at the end. So it’s a wonderful part, especially in my repertoire. Most of my roles have tragic endings, so I particularly like it. I’ve unfortunately only done it once onstage. But, yeah, it was fun with Thomas.

Do you ever find yourself stuck with unimaginative directors, and needing to work out stage business with other artists behind the director’s back?

I don’t think that, with this particular team, I will feel it necessary. This is the second week of the rehearsals, and I already know it’s going so well. All the elements are there.

Of course, you sometimes end up in a bad production where the director leaves you on your own with your colleagues. With good colleagues, it works out. But as a rule, to need to do it every night to finish the run, it’s a challenge, and it feels like work. But sometimes you have to do it.

The older I’ve become, I’ve learned a lot of lessons. I don’t work with directors whom I feel have betrayed me — they haven’t been good, or they’ve been interested in something else, or been badly prepared, or just haven’t the ability. Why waste time? Life is too short.

These days, I’m extremely selective of directors, and conductors too. The best thing success in your career and so-called fame give you is the artistic freedom to turn down the offers that involve people with whom you don’t want to work.

It also includes singers who have different goals than you do. I’m not interested in working with colleagues who are not interested in opera as a production. For me, opera is a production that is worked on together as a team. There is a clear team, and everybody is in it together with the same goal.

So the prima donna or don who strides in and only cares about themselves ...

... Or the conductor that comes a week before the opening night and gets nervous when he sees that the people are actually moving onstage! I’ve had this so many times.

Nobody talks about it. Always we talk publicly about the prima donna singers. But I think the undisciplined people, on some occasions, are the conductors. You come to rehearsal the last week, when the orchestra starts working, whereas the director has been working with the singers for many weeks and we might have created something interesting. Then comes the nervous conductor who is only concerned about the orchestra and is probably not so well prepared and is nervous when the singers are moving. So many conductors start breaking the things that are going on onstage because of their own nervousness; they just want the singers to stand and come close to him and sing.

I trust that if you are prepared and the conductor is prepared and the director is prepared and everybody is willing to be present from the beginning, then four weeks [of rehearsal] for this kind of opera, I think, is luxury. But in a process like this, when everyone is working for the first time and you’re called for four weeks, everyone, including the conductor, shows up.

Have you had role debuts when the conductor shows up very late in the process?

Yeah, when I was younger. I don’t work with those anymore. Famous names, too. But life’s too short. I’m saving their time and my own, because they only make me nervous. I only work with conductors who are, in my view, professionals in that they’re there when I start the rehearsals and take part in the process.

When I was a young singer in the ’80s, I learned this. I worked a lot with Claudio Abbado, and did a lot of his productions all over the place. With him, I got these opportunities to work with fantastic directors: Peter Stein, Luc Bondy, you name it.

As a young singer, I took it for granted, because there were four weeks of rehearsals, because Claudio Abbado sat there in every single rehearsal from the beginning. Then I learned, no, no, this is not the rule, this is only Claudio. But with the experience that I have over these 28 years that I’ve done this professionally, I pretty much know already the conductors to avoid when I want to work, for example, on a new part and make this kind of debut.

Claudio is a genius. I was so privileged. ... I didn’t even realize it when I started with him in 1985. We worked together until 2002, when he got sick. As a young singer, I didn’t realize how spoiled I was.

Maybe you were spoiled, and maybe you were lucky enough to get what you deserved.

Thank you.

Look, you’re a great artist. I know you’re giving up Tosca, reportedly because it’s not a good fit. But on the YouTube clip I recently saw, your high range was just gorgeous and shimmering. It was everything we’ve come to expect from you. What happened with the role?

I’m a perfectionist. Comparing so many other roles that I’ve done, I felt that I’d done it enough times to say to myself that I’m not pleased with the way I do this. I’m not good enough in this for myself. And I’m my harshest judge. I spoke with these words, approximately.

It’s just a choice. I don’t find [my decision] as special as you might, or the media might. For me, it was just a choice. I decided I do not enjoy the role the way I enjoy other roles, because I don’t feel that I’m good enough for myself in this. So then I put on, “For artistic reasons, I’m not good enough for myself in this.” [Laughs]

You’re 50. Many great singers now onstage — Renée Fleming, Anne Sofie von Otter, Susan Graham — have hit or exceeded 50 and are singing wonderfully. What is it like, at age 50, to play a 300-year-old woman?

I feel truly young. [Recovering from laughter]

Great. I was talking with Susan Graham about this recently. She said that she and Renée had just been talking about the vocal adjustments they need to make as they age. What is it like for you?

Yeah, some things have definitely changed. I don’t think so much about age as a number; I think of how I feel, how things feel. For example, I don’t know if I’m abandoning Tosca forever. An older singer, a very wise singer whom I admire very much, said to me in Finland, “Just wait. You never know.” But for now I’m quitting Tosca.

Everything is about choices. When you get older, you make adjustments. If you want to continue this, you have to look after yourself, which is a full-time job when you’re 50. If somebody else tells you otherwise, they are lying.

I personally feel that I sing better than ever. I feel free, and I enjoy singing maybe more than ever. Maybe because I sing less per year. Unlike many of my colleagues, I take long holidays, I look after myself, I have a life, I have a husband. I feel when I’m happy and rested — when I have the breaks after a role like this, when I have a long holiday — I can charge myself. I’ve taken maybe 10 or 11 performances off a year.

I’m not retiring anytime soon. Everything is about health. You think about health a lot when you are 50.

You can’t really decide how long you will sing. You will just see. But for now, the way I feel, I want to continue as long as I feel this good. I will try not to sing too much, and keep my life in balance.

Everything is my mind. When my mind is happy, I can go anywhere and do anything. But if my mind is stressed out for whatever reason, and I try to do this job, then I will get sick or not enjoy it. And if you don’t enjoy it, why would you like to continue?