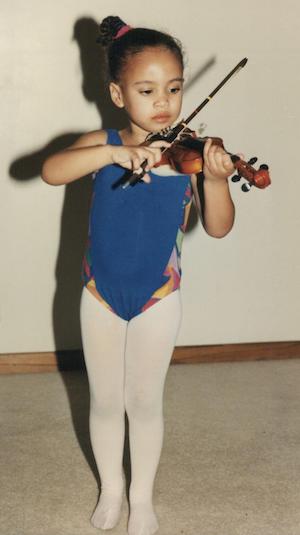

At age 29, violinist and composer Ezinma is making more than her mark as a classically trained musician. There are spokesperson contracts with major corporations, digital celebrity earned with viral covers of music by Post Malone, among other nonclassical musicians, pop-star status from appearances with Beyoncé (including the famous Coachella 2018 concert), and work with a plethora of musicians as mind-stretching as Stevie Wonder, Yo-Yo Ma, Kendrick Lamar, Joshua Bell, Clean Bandit, Sza, Mac Miller, A$AP Ferg, and more. Which is not to forget signing on with Decca Records, scoring a number of documentaries and films, starring in a documentary about her life and work, and developing an album of new music she has composed.

Remarkably, asked in a phone interview what she’d like to conquer next, especially as a composer, Meredith Ezinma Ramsay, the daughter of a Guyanese father and German-American mother, raised in Lincoln, Nebraska, doesn’t simply say, “I’m good.” Instead, she says, “That’s a great question. This is an exciting part of my career because it’s so fresh and new. I’ve been playing violin for 24 years and I’m excited for this new development in my career. To be a composer, as I continue to grow, I’d love to work with dance. To score a short ballet or even opera, something multidisciplinary. Another area interesting to me, in addition to ballets and films, is health and wellness and scoring experiences for healing. I’ve been going to things with gongs and stuff, but to have more of a chordal structure would be cool.”

With those words from Ezinma, welcome to more of her all-expansive world:

Every conversation these days seems to start with COVID-19, so let’s begin with how the pandemic it is impacting you personally and professionally.

I’m lucky I didn’t get sick and my immediate family is healthy. I give my sympathy to everyone suffering; the numbers are insane. I’ve used this time, when there’s so much of my normal life stopped as a performer and musician, to write a lot of music. I’m finishing up a Christmas record. I’ve also been taking a course at Berklee (College of Music in Boston) and thinking of getting another master’s in film scoring. I put in my application to start in January and finish in a year. It’s a great program and what I like is there’s a lot of modern production in addition to the classical composition and traditional stuff.

I wouldn’t have had the time and space in my normal life with shooting, traveling, touring, performing. I’ve also been doing virtual education (with young musicians). Before I worked with Beyoncé, I was working with students but I had to leave that because I wasn’t in a regular schedule anymore. It’s great to partner with [universities and schools] and connect with kids again.

Could you describe the parallels or contrasts you hear between white male composers who have long been held central in classical music and the artists you favor like Bob Marley, Billie Holiday, or the Parliaments? Or does this topic further perpetuate the centrality of white male composers and signal it’s time to move on?

One of my favorite composers is Beethoven. When you look at his life and career, he wasn’t always liked, he wasn’t always popular. He was pushing the boundaries. Listen to his late quartets: It’s so modern, it was not of the time. When I look at this man, so highly regarded, so revered, so incredible — I see he was pushing the limits and expectations. I see parallels to modern music.

As classical musicians, we’ve lost some of that wanting to push boundaries and challenge expectations. Some of these composers were writing, at the time, popular music. Bach was a popular musician, writing music you can dance to and listen to in corridors or chambers. I always keep in mind that Paganini was a rock star. He had women just wanting him. I always think of that when I’m doing remixes. I’m imagining what kind of composer would fit with Mozart, with Bob Marley.

I’m always making that connection because I love both worlds. I love the structure, tonality, and formality of a sonata, but at end of day, music is energy and so there are many connections [between modern and classical music] I try to have that in my remixes. Fusing those two worlds to show young who may not be familiar with the past that these things exist, but also to remind people in classical music that classical music is a vital music source. It’s not a decrepit, white, stuffy thing. It’s living and breathing today. We just have to reimagine it.

What can you tell me about your new recordings and the documentary recently made about your life?

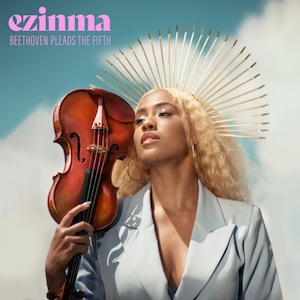

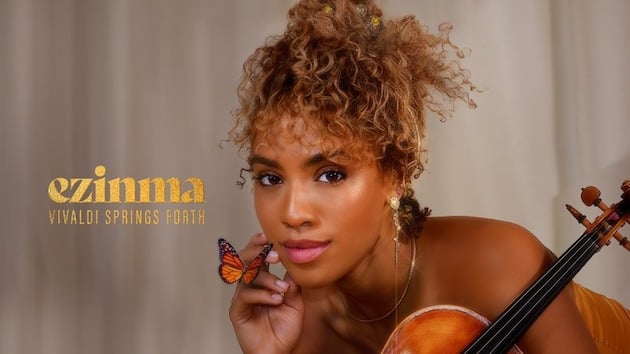

At the top of it, I’m dropping an EP called Classical Bae. It’s a culmination of a sound I developed in the past two years. The album features classical remixes: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Beethoven’s Fifth, the Bach solo cello suites, and Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. It’s coming out in February 2021. From there, my work is going to definitely be shifting to something more orchestral. Just being in the world of film music, there’s been more symphonic scoring, and the freedom in that music has been inspiring in my writing. Mixing full orchestral sound with trap music [subgenre of hip-hop] — because I write everything myself — it’s been interesting to experiment and to play with cinematic sound. That sound is what people will expect from the complete album, coming in 2021. The EP comes out the top of next year, the album later on.

There are actually two documentaries. One is a short film in partnership with the jewelry brand, Bulgari. It’s directed by Alison Chernick, who directed the Itzhak Perlman documentary. It’s about my life and influences. It comes out for the Tribeca Film Festival, but it was pushed back by COVID and rescheduled for next year.

You’ve said you never saw another classical violinist until you were a teen. What thoughts do you have about the importance of people of color seeing themselves up on the stage? What messages do you want to send, not just to artists of color, but to people of any race or ethnicity?

Visibility is so powerful. A lot of the decisions being made in boardrooms and companies are seldom made by people of color. Those effects trickle down. In the ’90s, you never saw even little things, like Black Barbie dolls. There was a white aesthetic. It’s important for the people in positions of power to remember to include as many voices as possible. That inspires kids. It creates unity, more diversity, more access. The effects multiply. [Black ballet dancer] Misty Copeland, she affects so many people’s lives. Or Serena Williams, these amazing women of color who are dominating not just white spaces, but their craft, their careers. Supporting women from minority groups is something we can continue to strive for, just to pass that torch. It needs to start in boardrooms, CEO rooms and offices, because that’s where decisions are made.

This access doesn’t have to be just racial. Diversity in all forms is important. We live in one of the most diverse countries in the world. There are so many stories, cultures, experiences. It is a shame to not tell those stories, and not let those voices be heard. What is represented should reflect the culture of the country or the community.

If we achieve greater representation for people of color, what would happen?

There’d be less self-hate. Less fear among people who feel they don’t belong. Less “I don’t look like the person who should be doing this thing.” It would have political impacts. If we lived in a place where there was more accountability and visibility, it would affect policy and create a more just, fair, and equitable world. If everybody could really be heard, it would help to balance an unfair world and system.

You have branded yourself as a commercial product spokesperson, video star, actor, classical-crossover musician, and beyond. Must those marketing skills now play into the training and development of all contemporary musicians, including classically trained musicians?

These days as a musician, you’re not just an instrumentalist. You have to know how to produce, make videos, brand yourself. It’s a multidimensional skill set. I work with people who allow collaboration. I have input so what I put out is truly representative of who I am and the messaging I want to send.

How much control do you have in the videography and other promotional tools representing you?

For the content I put on YouTube, even in official videos I put out, I’m incredibly hands-on. I know what my brand is. My social media videos are shot in one location; I say, “this is what I want to convey, this is the vibe, the song.” The videographer/director does the edits and then I do notes. The most recent [process] for my Christmas video, I wrote the treatment, what kind of shot I wanted, and sent it to the director. The one thing I’ve learned is the people who are brilliant at what they do, I want them to do that. I’ve learned to delegate and just let people know what I want to achieve.

Talk to me about your experience as a business woman as you build your nonprofit foundation, HeartStrings.

(HeartStrings is a music-based youth development program for children K-5 of diverse backgrounds. The HeartStrings Academy provides students with quality instruments, music instruction, leads children of color on field trips to concerts and includes community engagement activities related to classical music.)

It’s definitely a passion project; I want to give people more chances to learn instruments, especially kids. It came from my own journey. With COVID, everything got pushed back [because] it’s hands-on, physical, in-person lessons. The kids go to concerts in New York City and all of this stuff we can’t do [during the pandemic]. It’s not practical right now. But as an educator, I’ve been lucky. We have a space, instruments, a donor; it’s all coming together in ways I never knew would be possible.

It shows the power of relationships and building connections so as a team, you can achieve your goals and vision. The other work, when you play in a quartet or orchestra, there’s a kind of diva mentality in being a violinist. We can play really hard, play really fast — we’re just divas. But working on this foundation I have had to humble myself and become more of a team player. It’s been an interesting realization in this process.

Working with Beyoncé demonstrated to you the intensity of preparation she employs. What were some of the lessons and did they alter your approach or confirm your practices?

Seeing the preparation that goes into [her concerts] and the dedication affirmed the preparation you do as a classical musician for a recital or any performance. You have to know that sonata or whatever you are playing two-thousand percent. One hundred percent isn’t enough because you get nervous, strings break, babies cry. Beyoncé affirms my approach to preparation in general.

One thing that challenged or showed me something is that concerts should be an experience. It’s not enough to have people sitting and clapping dutifully and listening. Watching her intention to give to her fans feelings and excitement; everything was psychological. It’s not just the music being great and the dancing being perfect, it’s how is it affecting the audience? How is it changing their psyche?

I learned about the pacing of a show, programming. I’m interested in taking that and continuing to make it my own. Obviously, the production-value of her stuff is incredibly effective and I have no interest in doing that [level of production]. It’s not appropriate in what I do. But I learned about lights, different ambiences, different outfits, and looking at the audience. As an instrumentalist in classical music, we feel weird looking at the audience, but to smile at people and make them feel seen ... has had huge impact on the ways I do my performances.