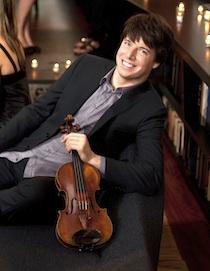

Photo by Mark Hom

If any violinist is a household name, it may be Joshua Bell, the 43-year-old superstar from Indiana. His dazzling virtuosity, heart-melting sound, and boyish good looks have earned him fans the world over. This season, Bell begins his appointment as music director of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, an ensemble he’ll bring to the Bay Area next spring as part of the San Francisco Symphony’s Project San Francisco. He’ll play his first set of the three-concert project on Oct. 5–9, treating audiences to the Glazunov Violin Concerto and to Tchaikovsky’s Meditation From “Souvenir d’un lieu cher,” under conductor Vasily Petrenko. SFCV reached him by telephone in a round-robin discussion with journalists from around the country, to talk about what keeps him going during the course of his 120 concerts per season.

You’ll be performing a work by Tchaikovsky in San Francisco. What is your opinion of him as a composer? Do you think he’s too flowery?

It drives me crazy when people say he isn’t on the level of Beethoven or Mozart. He’s not Beethoven or Mozart, he’s something different. It’s often said about some of the great Romantic composers that it’s not great music because it’s popular, therefore not profound. Same thing with literature: “if it sells too many copies, it can’t be good.” But I think Tchaikovsky is as great as it gets. His symphonies are very profound.

What about crossing over into even more popular styles, as you did with your recording At Home With Friends?

I love music, so there’s music I feel an affinity for, and music that I don’t. For example, I got to know friends of bassist Edgar Meyer, whom I attended school with at Indiana. He brought me into his bluegrass world, and it just feels like music. There is some modern classical music that I feel no affinity for, and it feels farther away from Beethoven than the bluegrass I play. The side benefits to doing an album with other types of musicians are that you reach audiences that you wouldn’t normally reach through their fan base — for example, Sting, or Josh Groban.

Is there an artist you’d like to collaborate with, but haven’t had the chance?

As a teenager, I was a fan of Genesis with Peter Gabriel and thought it would be nice to get to do something with him. Of course, I’m a big Beatles fan and only recently met Paul McCartney. I’ve been very lucky to work with many great conductors, but Carlos Kleiber [who died in 2004] is one I always wished I could work with.

I won’t stop my solo career, just do more with the ensemble [Academy of St. Martin in the Fields].

Tell us about your activities with Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.

I’ve played with them for years, but this is the first position I’ve had as music director where I’ve been involved to such an extent with one ensemble. I’m playing a concerto with them each time I play, but also directing a symphony from the concertmaster’s chair in the second half — about 30 concerts per year. I’m not waving a baton, but leading from within the orchestra. I won’t stop my solo career, just do more with the ensemble.

Do you program their entire repertoire?

Yes, the programs that we do together, especially. As music director, I approve their general schedule and repertoire, as well.

Your schedule often takes you to smaller cities. What does it mean to you to help grow those smaller orchestras?

I enjoy playing in smaller cities and with regional orchestras. Sometimes there is more of an appreciation for what we’re doing in places that don’t have a million things happening every night. Sometimes when you play in smaller cities, you’re more appreciated because it is a special event. And the orchestras often try harder than some of the major orchestras that play so many concerts in a year. They play with more enthusiasm.

Sometimes when you play in smaller cities, you’re more appreciated because it is a special event.

Your experiment with the Washington Post, busking in the subway incognito and filming people’s reactions, is still discussed. (See video.) What’s your take on that now?

It made people think about context in art, how they view art. It was successful in its objective in that way, but it wasn’t really a scientific experiment or anything. It got people to talk. I’ve heard that priests, rabbis, and Muslim imams have even used it as a parable, which is remarkable and surprising. I did it as a favor to a friend, journalist Gene Weingarten; I had a little fun and thought it would disappear in a week.

But was it strange to think that people come and pay a lot to hear you play in the concert hall, but did not stop in the subway?

It did make me think about that special atmosphere that happens when people are there with expectations, and ears ready to absorb what you’re doing, and brains ready to digest what you’re giving them. It made me realize that some music can’t be thrown at someone when they’re rushing to work. It’s a two-way street; you need a receptive audience. I have a great job, getting to play music for people who really listen and clap for me at the end.

What are the challenges of integrating family life into your very busy professional life, and what effect does that have on your artistry?

I have three little boys now, and it makes traveling more difficult since I get more homesick [Joseph is 4 years old and Bell’s twins are 1½]. I try not to be away for more than a few weeks maximum. I used to be gone for up to a month and not bat an eye, because I love traveling. The experience of being a parent is incredible; all of the emotional experiences, positive and negative, all affect your music and help you be a better musician. It’s not a job where you can live a normal Leave It to Beaver family life. You have to make adjustments.