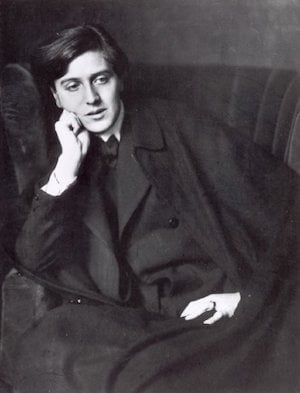

To listen to him talking about his nearly four decades of professional violin performance across the globe and four centuries of repertoire, you’d think that Gil Shaham was counting lucky breaks, rather than laurels. His brief bio, in the San Francisco Symphony’s press release about his upcoming performances at Davies and California tour with the orchestra, positions Shaham’s “inimitable warmth and generosity of spirit” alongside his “flawless technique.” These qualities are as apparent as his modesty in his phone conversation with SFCV from his family home in New York City, which he shares with his wife, violinist Adele Anthony, and their three children.

Shaham himself was born 47 years ago in Urbana, Illinois to a pair of Israeli scientists who returned their family to their homeland when their son was 2 years old. After his childhood orchestral debut with the Jerusalem Symphony and the Israel Philharmonic and his triumph at competitions, Shaham became a scholarship student at Juilliard. He was still a high schooler when he was called to replace an ailing Itzhak Perlman under the baton of Michael Tilson Thomas in London, and he went on to study at Columbia alongside his pianist younger sister, Orli. Winning a chamber-music Grammy with André Previn in 1999 on Deutsche Grammophon, Shaham went on to found his own record label, Canary Classics, in 2003. Though he’s regularly guested throughout the U.S., Europe, and Israel, Shaham and Anthony have both tailored their touring to provide for parenting. San Francisco, Shaham tells us, with an abiding trace of an Israeli accent, is something of a second home.

How is your weather there in New York?

We’re having a snow day, I’m looking out the window and it’s really coming down. They’ve canceled school. Are you a native San Franciscan, how long have you been there?

Almost 50 years, but, I grew up in Maine, with plenty of snow of my own. But you’ve been a regular visit to our city.

My older brother, Shai, did his postdoctoral work at UCSF in biochemistry, and they lived in the Sunset, so I used to go there all the time.

And your relationship with MTT goes back to his tenure with the London Symphony Orchestra, before we got him. Tell us how that meetup came about.

I was in high school, at the Horace Mann School, in Brooklyn, in English class, I was a junior. There was a knock on the door and a message: “Gil, can you come down to the principal’s office?” Which is pretty much the last thing anybody wants to hear. I went downstairs, and there was a phone call, from Byron Gustafson of ICM, I think it was. He said, “There’s a concert in London tomorrow. Itzhak Perlman has canceled, and the only way this would work would be if you were to leave school right now and get over to the airport and get on the Concord. And play the Bruch and the Sibelius.” I gave it maybe a split second of thought, and I said, “Yeah, sure!”

How did they happen to pick you?

I don’t really know the answer. I was lucky enough to have known Mr. Perlman before. Navah, his [pianist] daughter and I, had played chamber music together. I had played with the London Symphony before, and when he canceled, they were so desperate to get a violinist, I’m imagining the first 150 they called couldn’t make it, so I was lucky to be able to do it. I remember being very nervous before going on stage, and it was Michael [MTT] who talked me down. He said, “just go out and enjoy!”

And you did, and you were well-received.

I think I was very lucky, because it was a very slow news week, so suddenly I got a lot of attention. There were pieces in the newspapers and on television, and suddenly I had many more invitations to play concerts. Now, playing with Michael is something I cherish, and something I’ve done for many years, so I’m very much looking forward to coming again.

You actually played with the San Francisco Symphony before MTT became music director here.

It was in 1990, when Maestro Blomstedt was conducting, and it was the Mendelssohn Concerto. It was Peter Pastreich who invited me. Some of your musicians, including [violinists] Florin Pavulescu and Melissa Kleinbart, we went to school together, in the Huilliard Precollege Division, in the 1980s, and I've met some in other settings, in other orchestras and in chamber music. So I'll feel like this will be another reunion.

You’ll be doing the Berg Violin Concerto here this month, and recording it with the Symphony, as well as touring it. How does that figure in your history?

After my first meeting with MTT, over the next few years he used to tease me, or encourage me. It became almost a joke, like, “Nice to see you, and when are you going to learn the Berg?” Then we finally programmed it, I believe it was in Miami, with the New World Symphony. I really learned it because of Michael, and with him, and through him — he already was very familiar with it — so I really do credit him with introducing me to it.

What did you learn about the Berg?

I believe Berg wrote a letter to the parents of Manon Gropius. She was the daughter of the famous architect, Walter Gropius, and Alma Mahler [composer and ex-wife of Gustav Mahler]. She was like the second coming of Alma, and much beloved by Viennese society. And then she died, as a teenager, she was taken by polio [early in 1935]. I’ve heard that Berg’s letter to the parents said, "Words cannot express my sorrow, but maybe in a few months I can convey my feelings to you through a violin concerto." Then it ended up being his own requiem.

He died in December of 1935, from blood poisoning.

And he ended up never hearing the piece himself. When you ask me what I hear, I think of a very famous passage, at the beginning of the fourth movement (although the piece is officially in two movements, each has two distinct halves, which I would call “acts,” it’s very operatic). The first part is describing, in a very nostalgic, bittersweet way, Manon Gropius. The second describes her struggle with death. And then, her transcendence.

At the very beginning of the last section, there’s a passage where Berg reworks a melody from a Bach chorale, and the melody is even older, from a 17th-century Lutheran hymn [by Franz Joachim Burmeister and Johann Rudolf Ahle]: “I’m ready, Lord, if it pleases you to take my soul.” Berg repeats each phrase twice, the first time with this sort of weeping solo violin, over this very dissonant modern twelve-tone accompaniment in the orchestra. This particular tone row is bittersweet, because it’s major and minor, triads on top of each other. Then he repeats the exact same phrase in Bach’s original setting, with Bach’s own harmonies and counterpoint, with a group of clarinets and the orchestra. It really sounds like you’re hearing an organ from a faraway church.

And it’s a beautiful homage.

Yes, to Bach. But it was also Berg’s way to express this feeling of loss, a longing for something from the past, and the anxiety and fear of what will be, how we will move on. In a way, he really captured the feeling of Europe at that time, before the Second World War. The solo violin leads the strings of the orchestra, and one by one they join, till they’re all crying and lamenting together, and it forms this big collective of emotion.

Like a wailing wall of sound.

Yes. I love that.

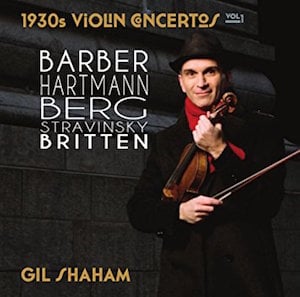

You’ve celebrated that period of time expansively on your two releases of concertos from the 1930s.

They were my excuse to play music that I love. If you look at the list of composers who wrote for the violin at that time, you have Stravinsky, Bartók, Prokofiev, Berg, Schoenberg, Hindemith, Britten, Walton, Barber, Sessions, Milhaud, Szymanowski — and I’m leaving out many. Bloch, Hartmann, Korngold — it’s really striking that there’s this confluence of concertos.

They were my excuse to play music that I love. If you look at the list of composers who wrote for the violin at that time, you have Stravinsky, Bartók, Prokofiev, Berg, Schoenberg, Hindemith, Britten, Walton, Barber, Sessions, Milhaud, Szymanowski — and I’m leaving out many. Bloch, Hartmann, Korngold — it’s really striking that there’s this confluence of concertos.

Do they have anything in common other than their period of gestation?

That’s a great question, but I don’t really know the answer. Someone said it’s the form of a single-voiced instrument, pitted against the orchestra (or society, or the world). The pieces are actually so diverse, such a mixture of styles. I just played the Bartók, and there’s a phrase which is a twelve-tone jazz waltz! [laughs]

I’d assume that having your own label, Canary Classics, allows you to better pursue what you really love.

I don’t know how many concertos we’ll get around to, but I was very lucky, in December, to have recorded the Korngold with [St. Louis Symphony Orchestra conductor] David Robertson, who is married to my sister, Orli. I guess I started the label about a dozen years ago, and it was a little bit of a risk, but I thought I’d been around long enough to have something of a following, but I was young enough still to take on risk like that. I feel very lucky, because what I learned very quickly was, from a business perspective, and also from an artistic perspective, there are many advantages to having control. I guess I’ve always had problems with authority anyway. [chuckles]

And you and your wife have more control over your time.

We both started working very young, and when we had kids, we were lucky enough to be able to cut back on our work. If she’s away on the road, I try to be home, and if I’m away, she tries to be home. What we love the most is being together.

Are the kids showing musical inclinations?

We have Elijah, and he’s 15, and Ella, she’s 12, and those two guys play violin. I think they enjoy it, because they practice every day, they listen to music, and they go to orchestra with their friends. And we have Simon, who’s six, he’s a pianist.

Any music making in the chambers of your family home?

Not as much as I’d like. But little Simon, last night he was playing the Turkish March, the Mozart, and he said, “let’s play it together!” So we did. And when the older kids learned to play the Bach Double, I was just so happy. That was my favorite thing in the world.