Stepping out on a classical-music high wire at the end of a stimulating conversation with two-time Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Xavier Dphrepaulezz — best known as Fantastic Negrito — I ask if he’d consider working with a symphony orchestra or an opera singer. After all, Negrito declines genre restrictions that try to peg his artistry as blues or funk or a blues-hip-hop-funk-soul-roots fusion. His music and its themes, he insists, are about practicing gratitude, honoring musical ancestors, anthemic declarations of purpose, and connecting to people on the street. “I call gratitude my religion,” he says.

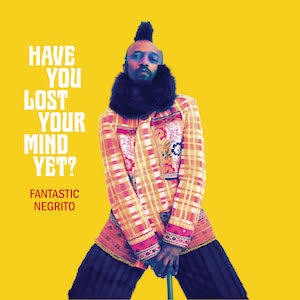

The East Bay-based musician’s third album due for an August release is provocatively titled Have You Lost Your Mind Yet? The 11-track CD features collaborations with Bay Area rapper E-40 and New Orleans jazz-soul group Tank and the Bangas. The album’s theme and a crowdsourced music video released in late May with the lead track “Chocolate Samurai,” explore a profile of worldwide mental health and express how people are coping with conditions created by the coronavirus pandemic lockdown, economic inequities, racism, xenophobia, bigotry, addiction — but also uplifting and energizing moments of love, joy, relationships, and laughter.

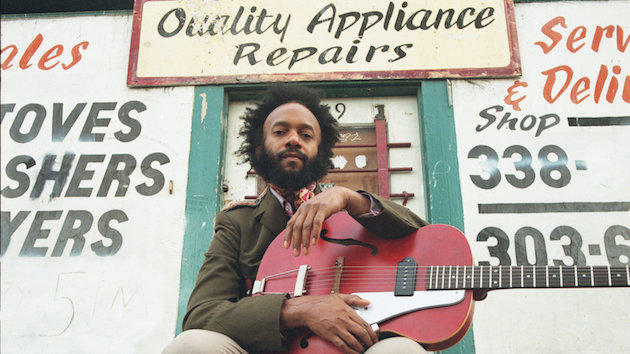

Negrito, the eighth child in a conservative Muslim family of 14 children, has survived life-threatening challenges with agility that rivals any nine-lives cat — most notably resurrecting a music career after an accident rendered one of his multi-instrumental hands less capable than it once was. His two Grammy-winning Best Contemporary Blues albums The Last Days of Oakland and Please Don’t Be Dead, and an NPR Tiny Desk Concert in 2015 bumped him into national and international focus.

Despite a worldwide tour postponed due to COVID-19, conducting record promotion activities while contemplating riots and protests raging across the country after an unarmed black man, George Floyd, died under the knee of a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and with everything about the future seeming uncertain and tumultuous, Negrito remains calm, serene, and seriously focused on making great music.

You told me you want to grow your universe: Do you think about classical music collaborations?

I want to expand my universe. The new album is the first collaboration with Tank and the Bangas (the group won an NPR Tiny Desk Concert in 2017 and joins Negrito on the track “So Happy I Cry”) and one with (rapper-songwriter) E-40 on the track “Searching For Captain Save a Hoe,” so I expanded a lot. I’m looking at projects with David Byrne and Sting and I don’t see living in this world as this style or that style. If it’s classical or rock, those are just titles. If there was a great classical musician who wanted to do great things, sure, I’d do it. But first, I’d ask, “What you got in your tank?" That’s how I like to approach music: meaning, passion, purpose.

What do you hear in the music people are making right now? Professionals, but also amateurs posting things online or contributing to your video?

In terms of music I’m listening to, having been around young people so much, the thing I’m constantly listening to is greatness. I’m listening to Steve Wonder and Queen and the root blues of Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker. I listen to Radiohead, because I’m trying to teach young people. And to Ella Fitzgerald. And I’m eating dinner to old stuff like Miles Davis. I’m listening to blues and stuff like that because it’s classic. I’m reaching back and playing Sly Stone and the Beatles and classic stuff. I give new stuff a try, like Travis Scott. I don’t know about their messages, but I understand why they’re making the songs they do. Approval of the message, that’s not my agenda. I’m listening to everything because listening is how you learn.

What I hear is people trying to do great things, to contribute. Whether you’re a poet, ballerina, musician, philosopher, or something else, we have to walk back to the roots. Then we have a chance. We have to ask, “Why does American music influence the world?” Funk, rhythm, roots music, blues, gospel, classical — it doesn’t matter. It has to have purpose. To strive for that feeds me. The seeds were planted a long time ago for me to practice gratitude for people who’ve done things before me.

For the track “Chocolate Samurai,” I was just in a funkier mood. But what I’m hearing now and, it’s important to say, with what happened in Minneapolis, black folks have to stop thinking we have the same rights and will be treated the same way as others are. You have to have the tools to deal with authoritarian hostility. How should you conduct yourself when you get stopped by the police? I don’t know if it’s immunity even if we make everyone aware of that. It’s so much pressure on your nerves by the time a black person is an adult.

It’s a system and it’s real. As a black person, you have to deal with racist brutality as if it’s going to happen to you. My father, with all his flaws — and he had many — he taught me you need tools, because these authoritarian, these people working from the same playbook as the Third Reich, well, it’s not a coincidence that this cop murdered this black man in broad daylight. There’s no surprise there. Trump has empowered a population of bigots. I don’t think he himself is a bigot: he’s just masterful at manipulation. He’s the master of stupid speak.

Does what you heard in the contributed videos sent to you during the crisis send a message about the music industry and its future? Do you foresee massive movement away from big name producers, presenters, and record labels?

I think absolutely the mainstream industry has done what it was supposed to do. But it’s like a snake that eats its own tail and eventually devours itself — I mean the industry in popular, mainstream music. There are only a few standouts. Because of that, people were mostly telling unchallenged stories about culture. I wrote the Please Don’t Be Dead [album] and that happened, and now with this new album I produced, it’s happening again for me to be outside of the mainstream and make something new.

You know, we’re crumbling, like a play where we keep doing the same parts. Something new has to come because this isn’t sustainable: we’re all ok with a ticking time bomb of racism, with goodbye middle class and mass school shootings. The way out of it for me is to have unification. Do things to benefit each other. Look beyond racial barriers, religions, and find coalitions.

What’s behind the tendency of people to want to classify or define an artist’s music in terms of others? Do you find it objectionable?

It’s human nature and doesn’t bother me. One thing I don’t do is read about myself. I have no interest in what journalists or people say about what I do. I’m not in that world. All I want to do is go out in the street and play music. I care for people in my community. I care about songs. I love the idea of crafting songs. People say I can make so much money if I package it this way or that. But I’m a middle-age man and I’m happy about a lyric or a lick that stirs my soul. It’s like I’m living in a bubble, but honestly — even friends criticize me for it — it’s a happy place. I get a kick out of ignoring the outside voices. It keeps my roots in the blues and funk.

I remember making Please Be Dead and thinking, is it a rock album? I remember the two Grammy’s. I had to be true to myself for the new album. I had to play every note for it to make sense. Because it’s about mental health, of you and of I, of my best friend.

Listen, if how many followers you have [on social media] determines your mood, it’s a strange world because you can buy those likes and followers. Music reflects that we’ve handed over the world to that. I want to step outside that and make albums that aren’t fake, with musicians who aren’t puppets asking for outside approval.

Let’s talk about a track on the new album: “Justice in America” is only 26 seconds long: How did you decide that was the right length?

This album was extremely cathartic. Every note, every lyric mattered — it was the hardest record I ever wrote and produced. It wasn’t quick to put this track together. The rapper, (Oakland-based) Gina Madrid, I loved her (Latino) accent. I thought it would make people afraid and it’s the best thing poor white people can listen to. It’s about money and the overseers in this country who can buy their way out of anything. It makes me giggle and think: statement, meaning.

Tell me about your relationship to the camera and the closeup shots in the video for “How Long.”

All the videos this time for this album really painted the picture. Everything was “we’re in COVID-19.” For “How Long,” I was thinking of the perpetrators of crime: the cop that killed our brother in Minneapolis. I wanted you to focus on my face. I picked a tribe in Africa that wears a neck ring. I wanted it to feel like I was in Bob Marley’s bottomless pit. It was better to just focus on my face and I actually cut all my hair off. It was pretty simple. The video and the lyrics embody human emotion and struggle and tragedy and a desire for an answer.

I was comfortable with the close-ups because, you know, I’m the eighth of 14 kids, so I was always an exhibitionist. I always wore the most outrageous outfits, even in third grade. I had no fear in front of the camera to show myself in a way I had not done before. How long do we keep accepting murdering people in America and say it’s OK? I think we shouldn’t be OK with Sandy Hook, still. That’s what empowered me on the video.

What surprised you in the answers you received when you asked the question “Are you losing your mind yet?”

The answers didn’t surprise me. I’m in tune with the vibrations of the earth. We’re there because technology pushed us there. I specifically asked them to answer “have you lost your mind yet?” Not “will you lose your mind.” It’s going to happen to everybody because we’re in the age of too much. We are more sophisticated and more advanced technologically, but we have the most medical problems and are more medicated than ever before. Music and a crowdsourced video are my way of connecting with people, with everyone going through this.

Were the videos uplifting?

Absolutely. I watch them now and think it made me so happy. In a time of such isolation, I get a big smile on my face every time I watch it. Here we are, people sharing our experiences and that makes us better.

How might your and other artists’ music note the suffering of COVID-19 and systemic racism, but also motivate change?

I want to say this with a lot of clarity: I think we are in this all together. A person gets sick in China, India, Belgium, anywhere, and it can affect you. With 100,000 dead in America, that’s heavy. Whether or not we want to acknowledge it, that black man killed in Minnesota affects all of us everywhere in the world. There’s always going to be ills and sickness in the world. Music is that spiritual medicine that heals. We can do it right and be good medicine; do it bad and create bad medicine. If you contribute to build up everyone, that’s what I want to do as an artist and a human on the planet.